When we picture the Scythians, the dominant image is one of fierce, nomadic horse-lords sweeping across the Eurasian steppes. The Greek historian Herodotus painted them as formidable warriors, skilled archers who drank from the skulls of their enemies. They left no cities, no written histories of their own. For centuries, they were a whisper on the edge of the civilized world, a people defined by their ferocity and their transience. But buried beneath the vast, rolling grasslands in monumental earth mounds known as kurgans, the Scythians left a very different legacy: a treasure trove of breathtakingly intricate goldwork that reveals a culture of staggering wealth and sophisticated artistic taste.

Among these treasures, one type of artifact stands out for its unique blend of function, status, and narrative power: the Scythian gold comb.

Grave Goods of the Steppe Lords

To understand the combs, we must first understand the kurgans. These were not simple graves but elaborate burial chambers for the Scythian elite—the chieftains, warrior-nobles, and their consorts. The Scythians believed in a vibrant afterlife that mirrored their earthly existence. A chieftain needed his weapons, his servants, his prized horses, and, most importantly, the symbols of his status. Gold was the ultimate symbol.

Unlike settled civilizations that invested their wealth in temples and palaces, the Scythians’ wealth was portable. It adorned their bodies, their clothing, and their horse tack. This “animal style” art, full of swirling beasts and dynamic predators, is a hallmark of Scythian culture. But when they came into contact with the Greek colonies on the northern shores of the Black Sea, something magical happened. Scythian patronage met Greek craftsmanship, resulting in a unique Greco-Scythian style that blended raw, nomadic energy with Hellenistic realism. The golden combs are perhaps the finest expression of this synthesis.

More Than an Ornament: The Comb as a Miniature Sculpture

These were not ordinary tools for grooming. While they did have functional teeth, often carved from a separate piece of gold or another material, their true purpose was to be seen. Worn in the hair or perhaps atop a headdress, a golden comb was an unambiguous declaration of power and immense wealth. Made of solid gold, they were heavy, valuable, and beautifully impractical for a life on the move.

What elevates them from mere ornaments to masterpieces of ancient art is the decoration. The top of each comb is a stage—a miniature, three-dimensional diorama bursting with life. They are not flat reliefs but fully realized sculptures in the round, designed to be viewed from all angles. The artists who made them were masters of their craft, capturing incredible detail, tension, and movement in a space barely a few inches wide.

The Solokha Comb: A Battle Frozen in Gold

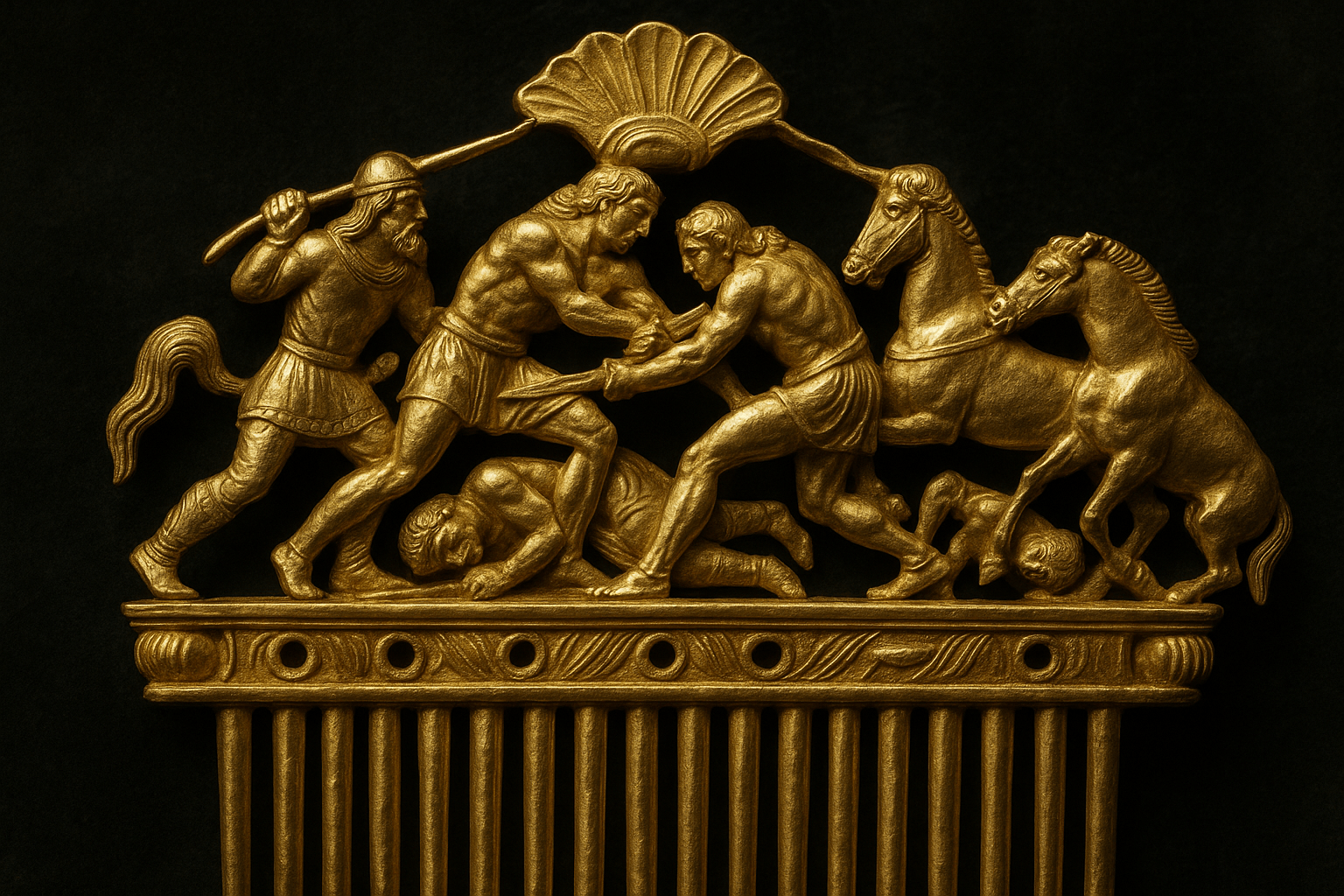

The most famous and spectacular of all is the comb from the Solokha kurgan, discovered in Ukraine in 1913. Dating to the early 4th century BCE, this solid gold artifact is a masterclass in narrative art. It depicts a dramatic and chaotic moment of combat.

The scene is dominated by a central figure, a Scythian nobleman on horseback. He is in the thick of battle, spear raised, charging at another warrior on foot. The details are astonishing:

- The Warriors: Every element of their appearance is rendered with ethnographic precision. We see their long hair, their tunics and trousers, and their Scythian-style armor, including scale mail shirts (gorytos) and protective greaves on their legs.

- The Action: The scene is not static. The horse rears, muscles tensed. The standing opponent braces himself for the rider’s charge, shield up and sword ready. A third figure lies on the ground next to a slain horse, a casualty of the preceding clash.

- The Composition: The artist masterfully created a sense of dynamic, swirling motion. The figures are not just placed next to each other; they interact, their bodies twisting and their implied lines of sight creating a powerful triangle of conflict. It feels like a freeze-frame from an epic film.

This single object is a historical document. It shows us, with more clarity than any written text, what a high-stakes Scythian duel looked like. It is a celebration of the warrior ethos that was central to their identity.

The Greco-Scythian Connection: Who Made These Masterpieces?

The immediate question raised by such sophisticated work is: who made it? The subject matter is purely Scythian. The clothing, the armor, the style of combat, the physical features of the men—it’s an insider’s view. However, the technique—the expert casting, the lifelike realism, the understanding of human and animal anatomy—is characteristic of Classical Greek art.

The scholarly consensus is that combs like the one from Solokha were created by Greek artisans, most likely from the wealthy trading colonies of Panticapaeum (modern Kerch) or Olbia on the Black Sea coast. These Greek craftsmen were commissioned by powerful Scythian chieftains, who provided them with a specific “brief”: depict us, our lives, and our values. The result was a perfect fusion. The Greek artist brought the skill, but the soul of the piece—its narrative and its spirit—is entirely Scythian. It is art made for Scythians, to their exact specifications.

This relationship was symbiotic. The Greeks received immense wealth in exchange for luxury goods, and the Scythians acquired status symbols that were not only valuable but also reflected their own cultural identity back at them in the most glorious possible medium.

An Enduring Golden Legacy

The Scythian gold combs are far more than just beautiful artifacts. They are windows into a lost world. They challenge our perception of nomadic peoples as “barbarians”, proving they were connoisseurs of magnificent and complex art. In these small, golden sculptures, we see the Scythians as they saw themselves: proud warriors, masters of the horse, and lords of the vast steppe.

Frozen in time, the rider on the Solokha comb continues his charge, a timeless testament to a people who, despite building no cities, left behind treasures that would echo their glory for millennia.