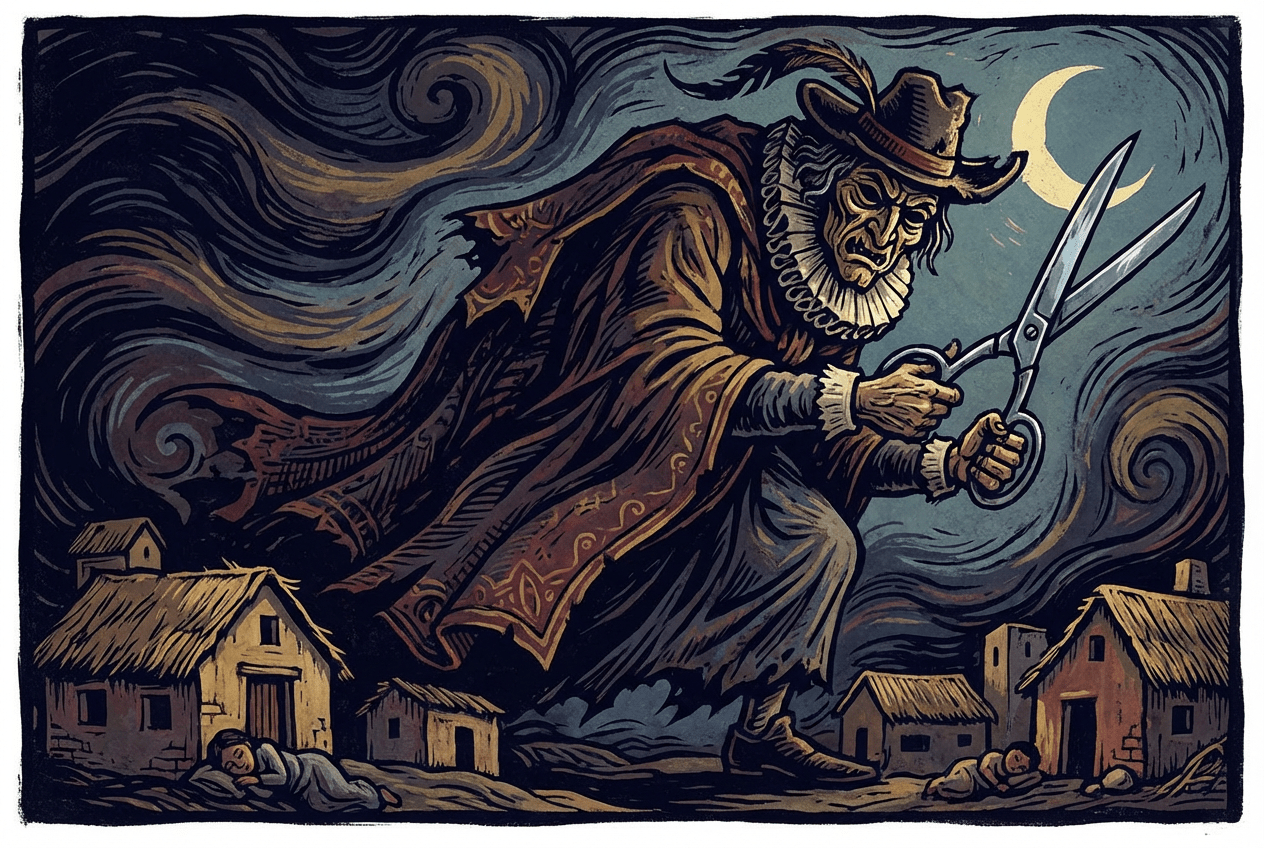

Imagine the Andean highlands in the 18th century. The air is thin and cold, the moonlight casting long, skeletal shadows across the rugged terrain. For the indigenous communities huddled in their homes, the greatest terror is not a mountain spirit or a mythical beast, but a man. He is tall, pale-skinned, and walks the lonely paths at night. He is the Pishtaco, the Scissor-Man, and he is hunting.

This sinister figure from Andean folklore is more than just a campfire story. The legend of the Pishtaco, which reached a fever pitch in colonial Peru, is a dark and powerful allegory for the trauma of colonial exploitation. It’s a story of fear, extraction, and dehumanization, where the very bodies of the colonized are rendered down to fuel the machines of their oppressors.

Who is the Pishtaco?

The name pishtaco derives from the Quechua word pishtay, which means to “behead”, “cut the throat”, or “cut into slices.” The descriptions, though varied, share a terrifying core. The Pishtaco is almost always an outsider—a white man (gringo) or sometimes a wealthy mestizo. He might appear as a solitary traveler, a priest in a long robe, a government official, or later, a foreign engineer.

His methods are brutally direct. Armed with a long, sharp knife, he ambushes lone indigenous travelers on remote mountain paths. He then kills his victims and carries their bodies to a hidden lair, where he butchers them and renders their fatty tissues into oil (grasa or unto). This human fat, according to the legend, had a variety of macabre uses:

- Lubricating the complex machinery arriving from Europe.

- Greasing church bells to make their tones clearer.

- Being exported to Europe as a magical, high-value cosmetic or medicine.

- Powering early trains and automobiles in later versions of the myth.

The defining feature of the Pishtaco is this act of extraction. He doesn’t kill for passion or revenge; he kills as a form of resource harvesting. The victim is not a person but a raw material, their life force and physical substance stolen for the benefit of a foreign power.

A Legend Rooted in Colonial Brutality

The Pishtaco is not a creature of pure fantasy. This horror story was born from the very real horrors of the Spanish colonial system in the Andes. For the indigenous population, the 18th century was a time of immense suffering, and the Pishtaco became a tangible embodiment of their deepest anxieties.

The connection between the myth and historical reality is starkly clear:

Forced Labor and Depopulation: The Spanish colonial economy, particularly in the silver mines of Potosí, ran on the forced labor of indigenous men under the brutal mita system. Millions were torn from their communities and worked to death in horrific conditions. From the indigenous perspective, the colonial state was literally consuming its population, draining the life and strength from their bodies. The Pishtaco, who drains the body of its fat, is a direct personification of this extractive system.

Mistrust of the Church: The Pishtaco often takes the form of a priest or friar. While some church members advocated for native rights, the institution as a whole was an integral part of the colonial power structure, responsible for the violent “extirpation of idolatries” and the destruction of Andean spiritual traditions. This deep-seated mistrust transformed the robed figure of the friar into a potential predator stalking the night.

Foreign Medical Practices: European medicine was alien and terrifying to Andean peoples. Practices like surgery and anatomical dissection, which violated cultural beliefs about keeping the body whole after death, were seen as a form of desecration. Spanish surgeons, with their strange metal instruments and their interest in the inner workings of the body, could easily be seen as real-life Pishtacos.

The Body as Fuel for the Colonial Machine

Perhaps the most potent element of the legend is the idea that human fat was used to lubricate European machines. This detail, which became more prominent as the Industrial Revolution began to ripple across the globe, is a chillingly precise metaphor. It suggests a world where indigenous bodies are literally the fuel for European “progress” and technological advancement.

The colonial system was, in essence, a giant machine designed to extract wealth—silver, gold, crops—from the Americas and transfer it to Europe. This machine cared nothing for the human cost. It ground down lives, families, and entire cultures. The Pishtaco story takes this abstract reality and makes it hideously concrete: a European comes, kills an Andean, and uses their body to make the gears of colonialism turn more smoothly.

The “Scissor-Man” is the human agent of this inhuman system. He is the face of an otherwise impersonal destructive force, a bogeyman born from the logic of exploitation. He embodies the ultimate dehumanization: the conversion of a human being into a mere commodity.

The Enduring Legacy of Fear

The Pishtaco did not disappear with the end of Spanish rule. The myth has proven remarkably adaptable, evolving to reflect new anxieties about foreign influence and exploitation. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the Pishtaco transformed into a railroad engineer, a foreign tourist with a camera, or a development aid worker. Any powerful outsider with unexplained technology or wealth could be a suspect.

Even today, the fear persists. In the 21st century, whispers of Pishtacos have been linked to organ trafficking rings. In 2009, a bizarre scandal erupted in Peru when a police general announced the capture of a “Pishtaco gang” that was allegedly killing people to sell their fat to European cosmetic companies. The story was later proven to be a fabrication by the police, but the fact that it was initially believed by many demonstrates the myth’s enduring grip on the collective psyche.

The Scissor-Man of Peru is a haunting figure that tells us a profound truth. Folklore is not just entertainment; it is history from below. It is the record of a people’s trauma, a coded narrative of their suffering. The Pishtaco continues to stalk the Andes because the fears he represents—of exploitation, dehumanization, and being consumed by outside forces—have never fully gone away.