Long before the hallowed colleges of Oxford and Paris dominated European learning, a different kind of intellectual powerhouse was humming with activity. Tucked away in the fertile plains of northern France, the cathedral school of Chartres became, for a brief but brilliant period in the 12th century, the epicenter of a philosophical renaissance. In an age often misremembered as “dark”, the scholars of Chartres were busy relighting the lamps of classical antiquity, not to replace the light of Christian faith, but to make it shine all the brighter. This was the stage for a grand synthesis—a bold attempt to unify God’s word with the logical framework of the ancient world.

A Cathedral School Unlike Any Other

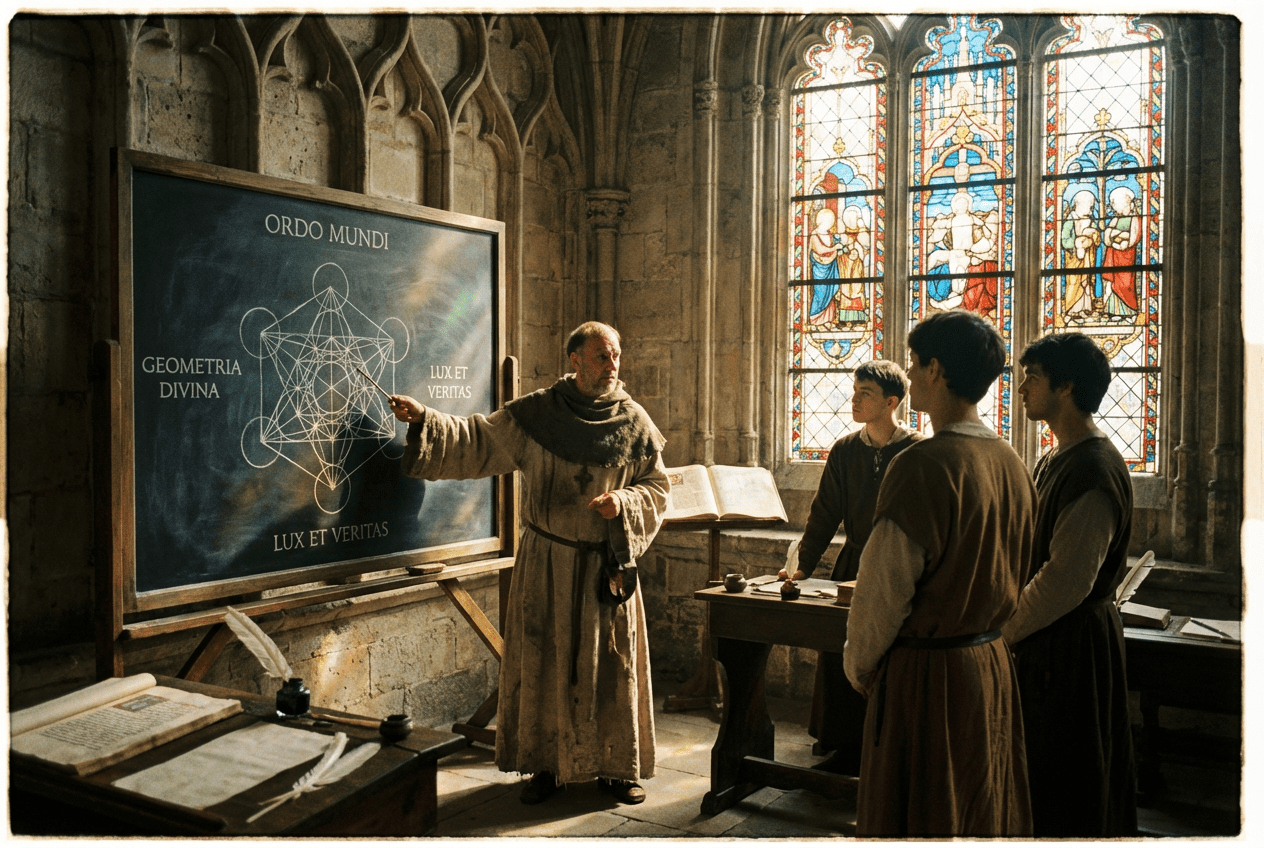

In the 11th and 12th centuries, cathedral schools were the primary institutions of higher learning in Europe. Attached to a bishop’s seat, their main purpose was practical: to train clergy in theology, liturgy, and canon law. Most were competent, but few were exceptional. Chartres was different. Its journey to preeminence began under the guidance of Bishop Fulbert in the early 11th century. A student of the great polymath Gerbert of Aurillac (who would become Pope Sylvester II), Fulbert established a curriculum at Chartres renowned for its quality and breadth.

But it was in the early 12th century that the school truly blossomed. As the magnificent Gothic cathedral we know today began to rise from the ashes of an older Romanesque structure, the intellectual edifice of the school was also being built. Masters and students flocked to Chartres, drawn by its reputation for a unique and invigorating approach to knowledge—one that saw no conflict between faith and reason.

The Seven Liberal Arts: A Ladder to Divine Truth

The foundation of the Chartrian curriculum was the seven liberal arts, a system of education inherited from late antiquity. For the masters of Chartres, these were not merely academic subjects; they were a structured path to understanding God’s creation. The arts were divided into two stages:

- The Trivium (the “three ways”): This was the bedrock of communication and critical thought, comprising Grammar (mastering language), Rhetoric (the art of effective and persuasive expression), and, most importantly, Logic or Dialectic (the art of reasoning and constructing sound arguments).

- The Quadrivium (the “four ways”): These were the mathematical arts, seen as the key to unlocking the structure of the physical universe. It included Arithmetic (the study of number), Geometry (the study of space), Music (the study of proportion and harmony, seen as number in time), and Astronomy (the study of celestial order, seen as number in space and time).

For the Chartrians, mastering the Trivium allowed one to analyze and understand scripture and the writings of the Church Fathers with unprecedented clarity. Mastering the Quadrivium allowed one to “read” the book of nature. They believed the cosmos was an ordered, harmonious system created by a rational God. Therefore, to study geometry in a flower’s petals or harmony in the motions of the planets was a form of theological inquiry—a way to appreciate the mind of the Divine Architect.

Plato in a Christian World

Perhaps the most distinctive feature of the School of Chartres was its profound engagement with the philosophy of Plato. While Aristotle would dominate the universities of the 13th century, 12th-century Chartres was a bastion of Christian Platonism. The scholars had limited direct access to Plato’s works, primarily knowing him through Latin translations and commentaries, most notably a partial translation of Plato’s creation-myth dialogue, the Timaeus.

The Timaeus was electrifying. It described a divine craftsman, the Demiurge, who fashioned the universe out of chaos by imposing a rational order based on perfect, eternal “Forms.” The Chartrian masters saw a powerful parallel. They eagerly identified the Demiurge with God the Creator and the Platonic Forms with the divine ideas in the mind of God. This philosophical framework provided them with a powerful tool to interpret the biblical creation story in Genesis.

For scholars like Thierry of Chartres, the six days of creation could be understood not as a literal 24-hour sequence, but as a logical unfolding of natural causes set in motion by God. This was a revolutionary attempt to harmonize the book of Genesis with a rational, “scientific” account of the cosmos. It was an argument that faith and natural philosophy (what we would call science) were not in conflict; they were two complementary paths to understanding the a single, divine truth.

The Masters of Chartres and Their Legacy

This intellectual ferment was driven by a series of brilliant masters whose influence spread across Europe.

Bernard of Chartres, chancellor in the early 12th century, famously articulated the school’s ethos. He is credited with one of the most enduring metaphors for intellectual progress:

We are like dwarfs perched on the shoulders of giants. We see more and farther than our predecessors, not because we have keener vision or greater height, but because we are lifted up and borne aloft on their gigantic stature.

The “giants” were the thinkers of classical antiquity—Plato, Cicero, Boethius. Bernard taught that one must build upon their wisdom, not discard it.

William of Conches took this to heart, writing extensively on natural philosophy and arguing that to neglect the study of nature was to neglect a key path to knowing the Creator. He pushed the boundaries of rational inquiry, sometimes drawing criticism from more conservative contemporaries who feared he was subordinating faith to reason.

Thierry of Chartres, Bernard’s brother, compiled the Heptateuchon, a monumental encyclopedia of the seven liberal arts, gathering all the essential classical and early medieval texts into a single, comprehensive curriculum. His work on harmonizing Genesis and the Timaeus stands as a high-water mark of Chartrian humanism.

Finally, John of Salisbury, a student at Chartres, became one of the 12th century’s most accomplished writers and thinkers. In his work Metalogicon, he penned a spirited defense of the Trivium—especially logic—against critics who deemed it frivolous. For John, logic was the essential tool that separated true knowledge from mere opinion, making it indispensable for theology, law, and governance.

The Road to the University

The golden age of Chartres was relatively brief, lasting from about 1115 to 1160. As the 12th century wore on, the intellectual center of gravity began to shift to the burgeoning schools of Paris, which would soon coalesce into a formal university. Paris became the focal point for the exciting rediscovery of Aristotle’s complete logical and philosophical works, and his system eventually eclipsed Chartres’ Platonism.

Yet, the legacy of Chartres was profound and enduring. The scholars it trained, the methods it pioneered, and the questions it dared to ask were carried to Paris and beyond. The Chartrian confidence in human reason, their rigorous application of logic to both scripture and nature, and their vision of an ordered, intelligible cosmos created the very intellectual climate in which the great universities and the scholasticism of Thomas Aquinas could flourish. They proved that faith did not require the abandonment of reason. The magnificent cathedral of Chartres, with its soaring vaults and luminous stained glass, remains a testament not only to medieval faith but also to the intellectual revolution that took place in its shadow—a rebirth of logic that paved the way for the High Middle Ages.