While the site is famous for the four cruciform tombs of Achaemenid Persian kings like Darius the Great, carved high out of the rock, it’s the series of reliefs at the cliff’s base that shout the loudest. These were commissioned by the Sasanian dynasty, rulers of the second Persian Empire from 224 to 651 AD. The Sasanians were the arch-rivals of Rome, and when they won, they made sure the entire world knew it. They didn’t just send messengers with news of victory; they chiseled it into eternal stone.

A Sacred Site for a New Dynasty

Why choose this specific cliff? The Sasanians were masters of propaganda, and their choice of Naqsh-e Rostam was a calculated political and religious statement. By carving their own monuments directly below the tombs of the legendary Achaemenid kings, they were visually and symbolically linking their new dynasty to the glories of the first Persian Empire. They presented themselves not as usurpers of the preceding Parthian rulers, but as the rightful heirs to Cyrus and Darius.

This was a place already steeped in royal and sacred power. The Sasanians simply added a new, dramatic chapter to its story, using the prestige of the past to legitimize their present rule.

The Divine Mandate: Ardashir I’s Investiture

The first and one of the most significant Sasanian reliefs belongs to the dynasty’s founder, Ardashir I. The scene is a masterclass in imperial ideology. We see two figures on horseback, both rendered in heroic scale. On the left is Ardashir I, receiving a diadem—the ring of kingship, or cydaris—from a figure on the right. This is no mere mortal; it is the supreme Zoroastrian deity, Ahura Mazda.

The message is unambiguous: Ardashir’s power is not self-proclaimed; it is a divine mandate. He is the chosen representative of God on Earth. But the story doesn’t end there. Beneath the hooves of Ardashir’s horse lies the crumpled body of Artabanus V, the last king of the Parthian Empire, whom Ardashir overthrew. Beneath Ahura Mazda’s horse lies the vanquished figure of Ahriman, the spirit of evil and chaos in Zoroastrianism. Ardashir’s victory is thus framed as both a political triumph and a cosmic victory of order over chaos, of good over evil.

Shapur I’s Masterpiece of Humiliation

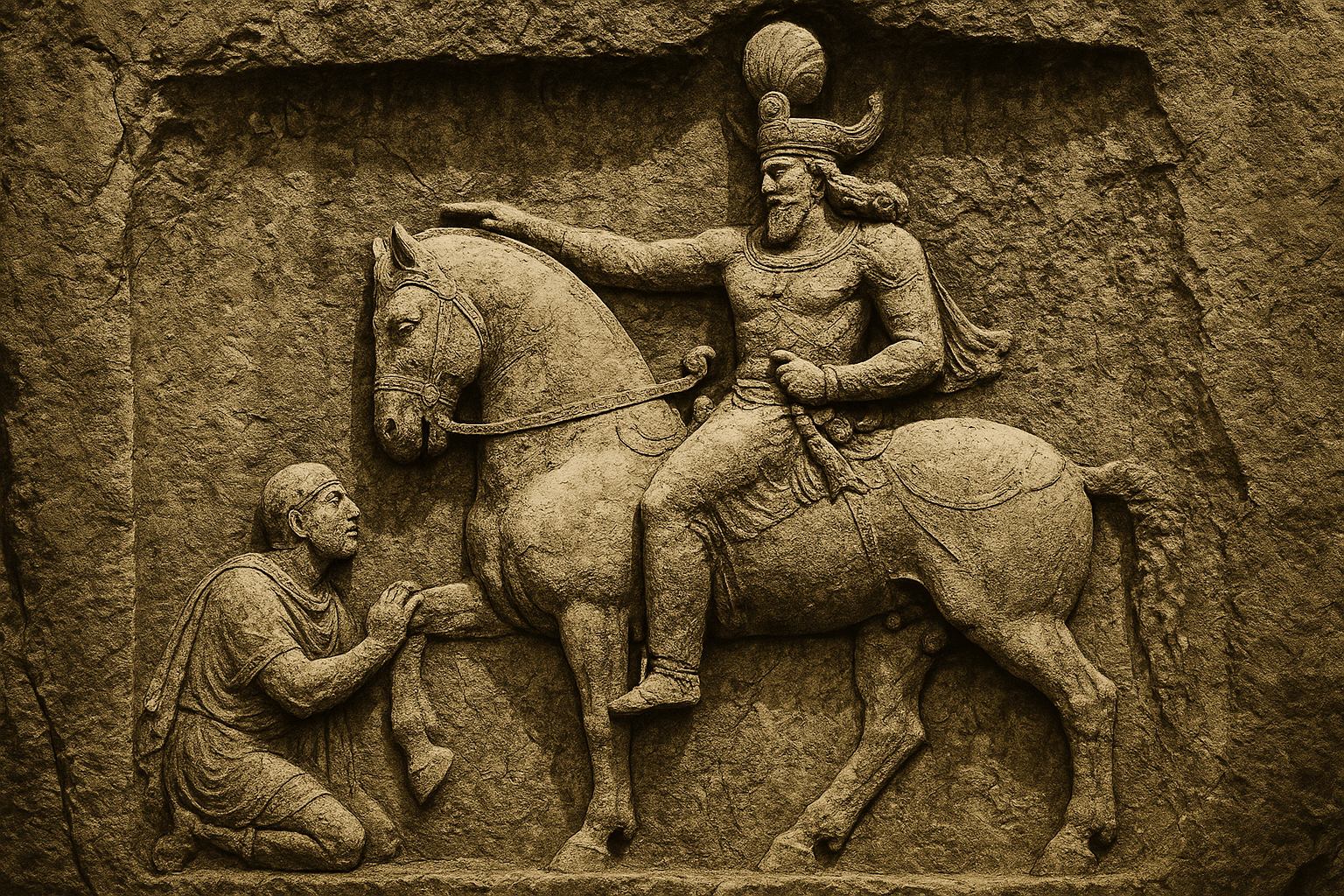

If Ardashir set the stage, his son, Shapur I, created the showstopper. Shapur was a formidable military commander who inflicted a series of devastating defeats on Rome, culminating in an event that sent shockwaves across the ancient world. His relief at Naqsh-e Rostam is perhaps the most famous and audacious piece of political propaganda from antiquity.

Carved with incredible detail and confidence, the relief shows Shapur I, regal and impassive on his horse. Before him are not one, but three Roman emperors, each depicted in a state of submission:

- Lying Prostrate: Under the hooves of Shapur’s horse lies the body of an emperor, identified as Gordian III, who was killed during a campaign against Persia in 244 AD. Whether he died in battle or was assassinated by his own men, the Sasanians claimed his death as a direct result of their military might.

- Kneeling in Supplication: A second Roman emperor, Philip the Arab, kneels before Shapur with his hands outstretched in a gesture of begging. After Gordian’s death, Philip was forced to sign a peace treaty and pay the Sasanians an enormous indemnity of 500,000 gold denarii to secure safe passage for his army. This carving immortalizes that moment of Roman submission and financial tribute.

- Captured by the Hand: The most shocking figure is the one standing, whose wrist is firmly grasped by Shapur. This is the Emperor Valerian. In 260 AD, at the Battle of Edessa, Valerian was captured by Shapur—an unprecedented and catastrophic humiliation for Rome. No Roman emperor had ever been taken alive by a foreign enemy. Sasanian accounts tell of Valerian living out his days as Shapur’s prisoner, and some Roman sources even claim he was used as a human footstool for the king to mount his horse. The relief captures the moment of absolute dominance, with the Sasanian “King of Kings” literally holding the Roman Caesar captive.

This single carving was a narrative of sustained Sasanian supremacy. It told the world that Rome could be defeated, its emperors killed, forced to pay tribute, and even captured. For any Roman ambassador, foreign dignitary, or local subject traveling this road, the message was inescapable: Rome is mortal, but the Sasanian king is eternal.

A Gallery of Imperial Power

The tradition continued after Shapur. Other reliefs at Naqsh-e Rostam depict subsequent Sasanian rulers in various scenes of triumph and investiture. The warrior-king Bahram II is shown in two reliefs: one as a heroic equestrian lancer charging down an enemy, and another in a more intimate family portrait, flanked by his queen and courtiers. King Narseh, who also fought the Romans, had his own investiture relief carved, this time receiving the ring of power from the goddess Anahita.

Each relief added to the dynasty’s legacy, reinforcing the themes of divine favor, military prowess, and unshakable authority. The artistic style is distinct—a blend of realistic detail, particularly in the Roman armor and figures, with the stylized, almost static grandeur of the Sasanian monarchs, identified by their impossibly intricate and individual crowns.

Today, the Sasanian Empire is long gone, eclipsed by the Arab conquests of the 7th century. Yet, on the sun-beaten cliffs of Naqsh-e Rostam, their defiant legacy endures. The reliefs are more than just magnificent works of art; they are a window into the psyche of an empire and its complex, violent, and deeply intertwined relationship with Rome. They are a permanent reminder of a time when the Emperors of Persia didn’t just defeat their rivals—they gloated about it in stone for all eternity.