Humble Origins: Protecting the Pilgrim’s Path

The story begins in the aftermath of the First Crusade. In 1099, Christian armies captured Jerusalem, and a flood of European pilgrims began making the perilous journey to the Holy Land. The roads were far from safe; bandits and marauders frequently preyed on these vulnerable travelers, robbing and killing them with impunity.

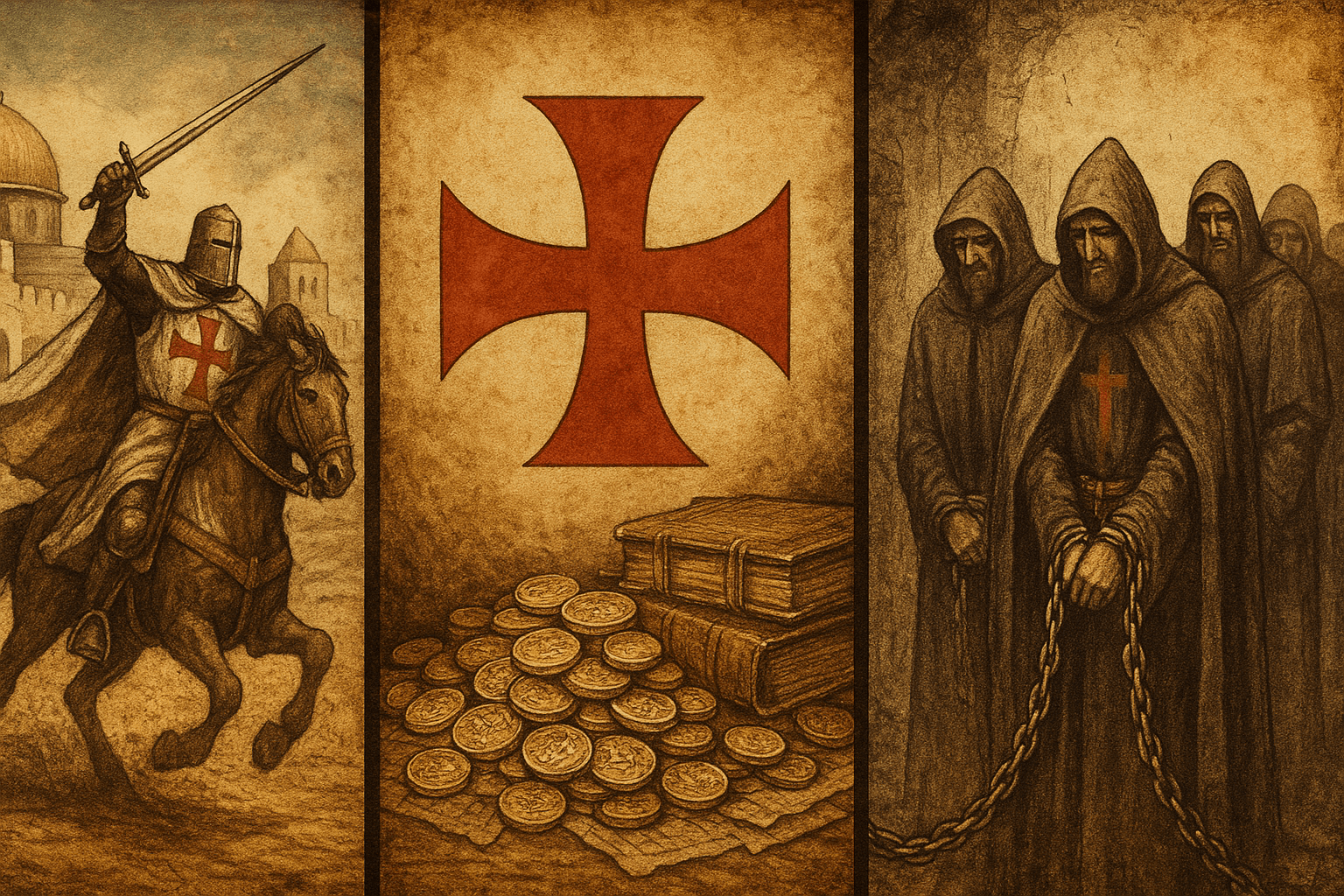

Around 1119, a French nobleman named Hugues de Payens and eight other knights saw a need. They approached Baldwin II, the King of Jerusalem, and proposed the formation of a monastic order dedicated to protecting these pilgrims. The king agreed, granting them headquarters in a wing of the Al-Aqsa Mosque on the Temple Mount, a site believed to be the ruins of the Temple of Solomon. This location gave them their famous name: the Knights Templar.

Initially, they were true to their official title: “The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ.” With no real financial backing, they relied on charity. Their original seal famously depicted two knights sharing a single horse, a symbol of their poverty and brotherhood.

From Poverty to Papal Power

For nearly a decade, the order remained small and obscure. Everything changed in 1129 at the Council of Troyes. Championed by the influential Cistercian abbot Bernard of Clairvaux, the Knights Templar were officially recognized by the Church and given a strict set of rules to live by—the Latin Rule. Bernard’s passionate advocacy cast the Templars not merely as guards but as a new kind of holy warrior, blending the life of a monk with the duty of a soldier.

The true turning point came in 1139 with the papal bull Omne Datum Optimum. This decree, issued by Pope Innocent II, granted the Templars unprecedented privileges:

- They answered directly and only to the Pope, bypassing the authority of local kings, lords, and bishops.

- They were exempt from all taxes (tithes).

- They were permitted to build their own churches and chapels.

These privileges transformed the order. Donations of money, land, and noble-born sons poured in from across Europe. The Templars became the elite shock troops of the Crusades, easily identified by their white mantles emblazoned with a red cross. Their discipline, training, and fanatical bravery were legendary. At the Battle of Montgisard in 1177, for instance, a small force of a few hundred Templars helped a Crusader army led by the leprous boy-king Baldwin IV defeat a massive army of over 20,000 led by the great Sultan Saladin.

The World’s First International Bankers

While their military fame grew, the Templars were quietly building an economic empire. Their most significant innovation was a system that can be considered the forerunner of modern banking.

A noble planning a pilgrimage to the Holy Land faced the risk of being robbed of all his gold along the way. The Templars offered a solution. The noble could deposit his funds at the Templar preceptory in London or Paris and receive a coded letter of credit. Upon arrival in Jerusalem or Acre, he could present the letter to the Templars there and withdraw his money. This made travel immeasurably safer and built immense trust in the order.

This network of finance soon expanded. The Templars began issuing loans to monarchs and nobles, managing estates, and holding valuables in their fortified vaults. Their Paris Temple became the center of French finance. In an age of feudal fragmentation, they were a uniquely stable, trustworthy, and continent-spanning institution. Their wealth became immense, and with it, their power and influence.

The Fall: A King’s Greed and a Friday in October

The Templars’ primary reason for existence was the defense of the Holy Land. When Acre, the last Crusader stronghold, fell to the Mamluks in 1291, that purpose vanished. The order retreated to its bases in Cyprus and Europe, but it was now a military force without a war to fight. Their immense wealth, secrecy, and immunity from local laws began to breed resentment and suspicion.

Nowhere was this more true than in France, ruled by the ambitious and ruthless King Philip IV. Known as “Philip the Fair”, the king was deeply in debt—much of it to the Templars themselves. He saw the Templars as a “state within a state” and coveted their vast treasury. He concocted a diabolical plan to destroy them and seize their assets.

At dawn on Friday, October 13, 1307—a date often cited as a possible origin for the “unlucky Friday the 13th” superstition—Philip’s men launched a coordinated raid, arresting every Templar in France, including the Grand Master, Jacques de Molay.

The knights were charged with a shocking list of offenses, including heresy, spitting on the cross during secret initiation ceremonies, idol worship (of a mysterious head named “Baphomet”), and institutionalized homosexuality. Under extreme torture administered by royal agents and the Inquisition, many knights confessed to the fabricated charges.

Dissolution and an Enduring Legend

Pope Clement V, a Frenchman heavily influenced by the king, was initially skeptical but eventually bowed to Philip’s pressure. While the trials across Europe outside of France yielded few confessions and little evidence, the damage was done. At the Council of Vienne in 1312, Clement formally dissolved the Knights Templar, not on the grounds of proven guilt, but because the order’s reputation was too tarnished to continue.

Their assets were ordered to be transferred to their rivals, the Knights Hospitaller, but King Philip ensured a massive portion found its way into his own coffers. Many knights who later recanted their forced confessions were burned at the stake as relapsed heretics.

The final, tragic act came on March 18, 1314. Jacques de Molay, the last Grand Master, was brought before a crowd in Paris to repeat his confession. Instead, he and another Templar leader, Geoffrey de Charney, defiantly proclaimed their innocence and the innocence of the order. Enraged, Philip ordered them burned at the stake that very evening. According to legend, as the flames engulfed him, de Molay cursed both King Philip and Pope Clement, declaring they would both follow him to judgment within a year. In a stunning coincidence, both men were dead before the year was out.

The Knights Templar were gone, but their legacy—a cautionary tale of faith, power, greed, and paranoia—endures. Their story continues to fuel countless myths of hidden treasures, secret bloodlines, and clandestine survival, ensuring that the Knights Templar remain one of history’s most fascinating and controversial subjects.