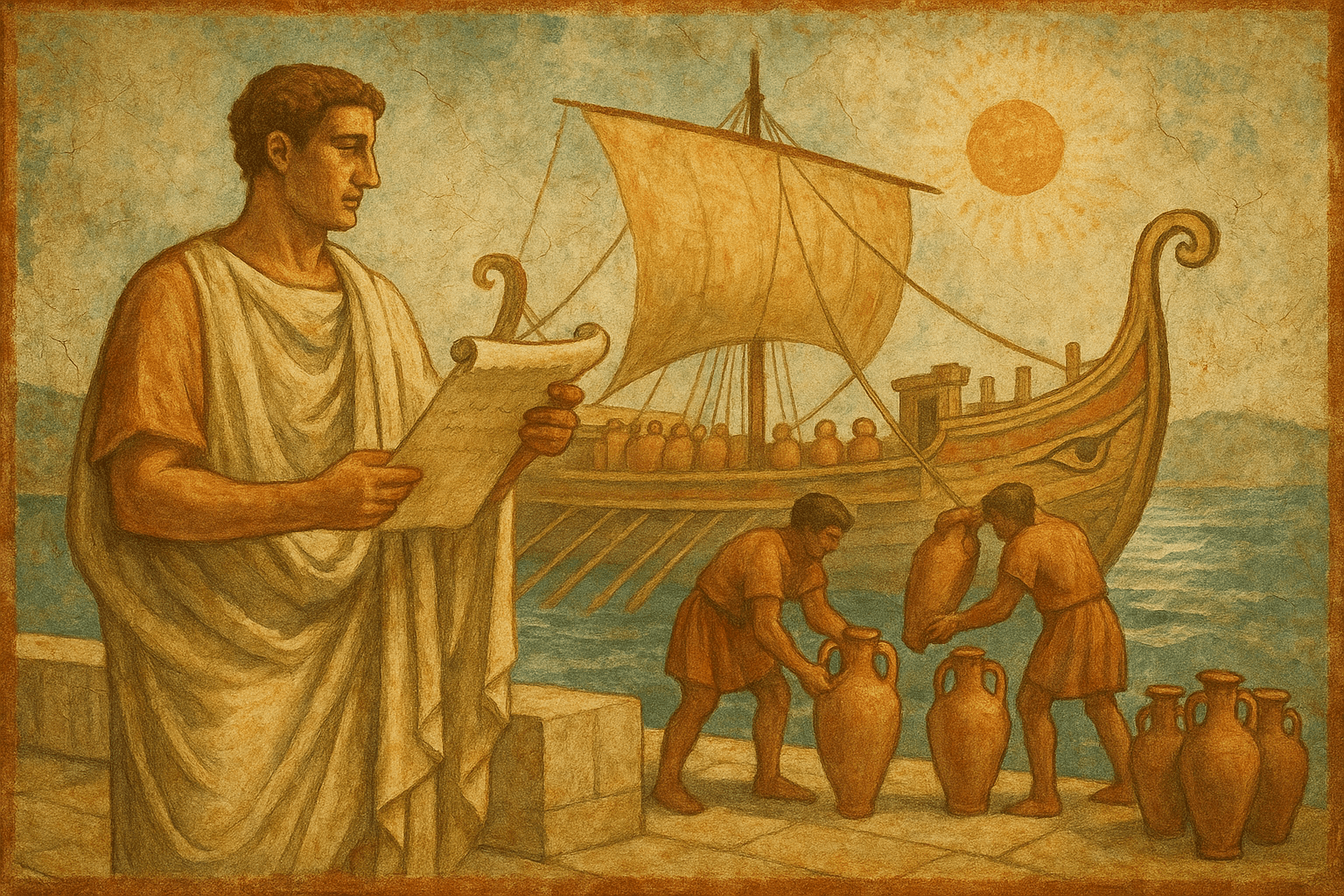

Imagine the choppy, unpredictable waters of the ancient Mediterranean. A merchant vessel, heavy with amphorae of wine, Egyptian grain, and fine silks, is caught in a sudden, violent storm. Waves crash over the deck, the mast creaks, and the ship begins to take on water. The captain, facing a terrifying choice, orders his crew to start throwing cargo overboard—jettisoning it—to lighten the load and save the ship. The vessel survives, limping into the port of Ostia. But now a new storm brews: whose loss is it? The merchant whose precious cargo now lies at the bottom of the sea is ruined, while the others whose goods remained safe have lost nothing. Was this fair?

In the perilous world of ancient seafaring, this was a constant risk. Before complex insurance policies and global maritime courts, how were such disputes settled? The answer for much of antiquity, including the mighty Roman Empire, was a remarkably sophisticated code known as the Rhodian Sea Law.

From a Small Island to an Imperial Standard

The Rhodian Sea Law, or Lex Rhodia, was not a single book of statutes handed down from on high. Rather, it was a collection of established customs and legal principles that evolved on the Greek island of Rhodes during the Hellenistic period (roughly the 3rd to 1st centuries BCE). Rhodes, strategically located, became a dominant naval and commercial power. Its livelihood depended on a smooth, predictable, and fair system for maritime trade. The laws that developed there were so practical and equitable that they became the de facto standard across the Mediterranean.

When Rome began its ascent, it was primarily a land-based power. But after defeating Carthage in the Punic Wars, Rome found itself the master of the sea. Its legions were now supplied by vast merchant fleets, and its cities fed by immense grain shipments from Africa and Egypt. With this explosion in maritime commerce came an explosion in maritime disputes. Instead of reinventing the wheel, the famously pragmatic Romans did what they did best: they adopted and adapted a system that already worked.

The Roman endorsement of the Rhodian Law is famously captured in an account by the jurist Julius Paulus. When a group of merchants who had been shipwrecked and plundered complained to the Emperor Antoninus Pius, his response was a masterclass in Roman legal thinking:

“I am indeed lord of the world, but the Law is the lord of the sea. This matter must be decided by the sea-law of the Rhodians, provided that no law of ours is opposed to it.”

This statement is extraordinary. It shows the Emperor himself deferring to a non-Roman legal tradition, recognizing it as the supreme authority in its domain. The Romans integrated the Rhodian Law into their own legal framework, giving it the weight of imperial power and ensuring its spread across the known world.

The Pillars of the Law: Fairness on the High Seas

The Rhodian Sea Law addressed the most common and contentious issues of seafaring. Its core principles were designed to balance risk and promote cooperation for the common good.

General Average: Sharing the Sacrifice

The most famous and revolutionary principle of the Rhodian Sea Law was the concept of “general average” (*Lex Rhodia de Iactu* — “the Rhodian Law concerning things thrown overboard”). This directly addressed our opening scenario.

The law stated that if cargo was jettisoned deliberately to save the ship and the rest of the voyage’s venture, the loss would not be borne solely by the owner of that specific cargo. Instead, the loss was to be shared proportionally by everyone who benefited from the sacrifice—that is, the shipowner and all the other cargo owners whose goods were saved.

For example, if Merchant A’s wine was thrown overboard to save the ship carrying Merchant B’s grain and Merchant C’s textiles, then Merchant B, Merchant C, and the shipowner would all contribute to compensate Merchant A for his loss. The value of the saved ship and saved cargo would be assessed, and each party would pay a share of the loss equivalent to their share of the total saved value. This brilliant principle transformed a potential source of conflict into an act of shared risk. It incentivized captains to make the right decision for the safety of the entire venture, knowing the financial consequences would be distributed fairly.

Loans, Salvage, and Responsibilities

Beyond general average, the Rhodian code provided guidance on other critical matters:

- Maritime Loans (Bottomry & Respondentia): The law recognized a form of high-risk loan that was a precursor to modern marine insurance. A captain could take out a loan using the ship as collateral (a “bottomry” loan) or the cargo as collateral (a “respondentia” loan). These loans carried very high interest rates. However, if the ship or cargo was lost at sea, the debt was completely forgiven. The high interest was the lender’s reward for taking on the immense risk of total loss.

- Shipwreck and Salvage: The law set rules for what happened after a wreck. It established the rights of the original owners to their property, even if it washed ashore, discouraging the “finders keepers” mentality that often led to looting. It also provided for fixed rewards for salvagers who recovered goods, encouraging rescue and recovery over theft.

- Contracts and Liability: The code outlined the responsibilities between the shipowner, the captain (master), the crew, and the merchants. It likely covered everything from crew wages and the master’s authority to liability for damage to cargo caused by negligence, such as improper storage or rat infestation.

The Enduring Legacy of Roman Maritime Law

The Rhodian Sea Law did not vanish with the Roman Empire. Its principles were so foundational that they sailed right through history. The Byzantine Empire preserved them in its 9th-century legal code, the *Basilika*. From there, they flowed into the great medieval sea codes of Europe, such as the Rolls of Oléron in France and England, the Laws of Wisby in the Baltic, and the Consulate of the Sea in Barcelona.

Most remarkably, its core concept lives on today. The principle of “general average” is still a fundamental part of modern international admiralty law. When a container ship captain today makes the difficult decision to jettison containers to save the vessel from a fire or grounding, the resulting financial loss is still apportioned among the shipowner and all the cargo owners, just as it was in the time of Emperor Antoninus.

The Rhodian Sea Law stands as a powerful testament to ancient ingenuity. It was a legal framework born from practical need, built on principles of fairness and shared risk, and robust enough to be embraced by the Roman Empire. It created the stability and predictability necessary for commerce to flourish across the seas, and in doing so, laid the very keel of Western maritime law that continues to guide us on the world’s oceans today.