The real story is more complex, more tragic, and far more fascinating. It doesn’t revolve around a fictional American captain, but around a very real Japanese hero: Saigō Takamori. He wasn’t a simple reactionary fighting against the future; he was one of the key architects of modern Japan, a man who found himself leading a rebellion against the very world he helped create.

The Man Who Built the New Japan

To understand the tragedy of Saigō Takamori, you must first understand his role in the Meiji Restoration of 1868. Far from being an enemy of the Emperor, Saigō was one of the “Three Great Nobles” who masterminded the overthrow of the centuries-old Tokugawa Shogunate. He was a leading general and statesman from the powerful Satsuma domain (modern-day Kagoshima prefecture).

Saigō was a paradox: a giant of a man, renowned for his physical presence and martial skill, yet also a thoughtful leader deeply committed to the samurai code of bushidō—honor, loyalty, and self-sacrifice. He believed that restoring direct imperial rule was the only way to strengthen Japan and prevent it from falling victim to Western colonial powers, a fate he saw befalling China.

He was, in short, a modernizer. He and his allies propelled Emperor Meiji to power, ushering in an era of dizzying, radical change aimed at transforming Japan from a feudal society into a centralized, industrial nation-state. Their slogan was Fukoku Kyōhei: “Enrich the Country, Strengthen the Army.”

Modernity’s Unforgiving Blade

The new Meiji government moved with breathtaking speed. To centralize power and create a modern nation, they had to dismantle the old feudal structure. Unfortunately for the samurai, they were the old feudal structure. A series of edicts systematically stripped them of their status, purpose, and livelihood:

- Abolition of Domains (1871): The samurai’s local domains were replaced with prefectures controlled by the central government, severing the lords’ power and the samurai’s regional loyalties.

- Universal Conscription (1873): A new national army was created, composed of conscripted commoners. This single act made the samurai class, a hereditary warrior elite, obsolete. Their monopoly on violence was gone.

- The Sword Ban (1876): The Haitōrei Edict forbade samurai from wearing their two swords, the daishō, in public. This was more than a disarmament law; it was a profound symbolic humiliation, stripping them of the most visible marker of their identity.

- Loss of Income: Samurai stipends, paid in rice, were converted into government bonds. For many lower-ranking samurai, this meant a sudden and catastrophic loss of income.

In less than a decade, the samurai class went from being the ruling elite to an disenfranchised and unemployed group. Their reason for being had been legislated out of existence by the very government many of them had fought to install.

The Breaking Point: A Quarrel Over Korea

Discontent simmered across Japan, but it was Saigō Takamori who became its reluctant figurehead. The breaking point came in 1873 over a debate known as the Seikanron, or the “Debate to Conquer Korea.”

Saigō argued for a punitive expedition against Korea after it refused to recognize the legitimacy of the Meiji Emperor. His motives were complex. On one hand, he saw it as a way to reassert Japan’s national honor. On a deeper level, he saw it as a noble cause for the thousands of disillusioned samurai, a way to give them a purpose and allow them to die honorably in a way their new society no longer permitted.

He even volunteered to go to Korea himself as an envoy, fully expecting to be assassinated, which would provide Japan with the perfect pretext for war. However, other leaders in the government, focused on internal modernization, argued that Japan was not yet ready for a foreign war. They vetoed the plan.

Feeling betrayed, Saigō resigned from his government posts and retreated to his home in Kagoshima. He became a magnet for disgruntled former samurai. He founded private academies (shigakkō) that focused on traditional martial arts and Confucian ethics, preserving the old ways. While not explicitly planning a revolt, he was creating a powder keg of traditionalist sentiment in the heart of modernizing Japan.

The Satsuma Rebellion: Honor Against Industry

The spark came in 1877. The central government, wary of Saigō’s growing influence, tried to remove weapons from the Kagoshima armory. Rumors also spread of a government plot to assassinate Saigō. Enraged, his followers—now numbering in the tens of thousands—implored him to lead them in a march on Tokyo to “question” the government.

Reluctantly, Saigō agreed. The Satsuma Rebellion had begun.

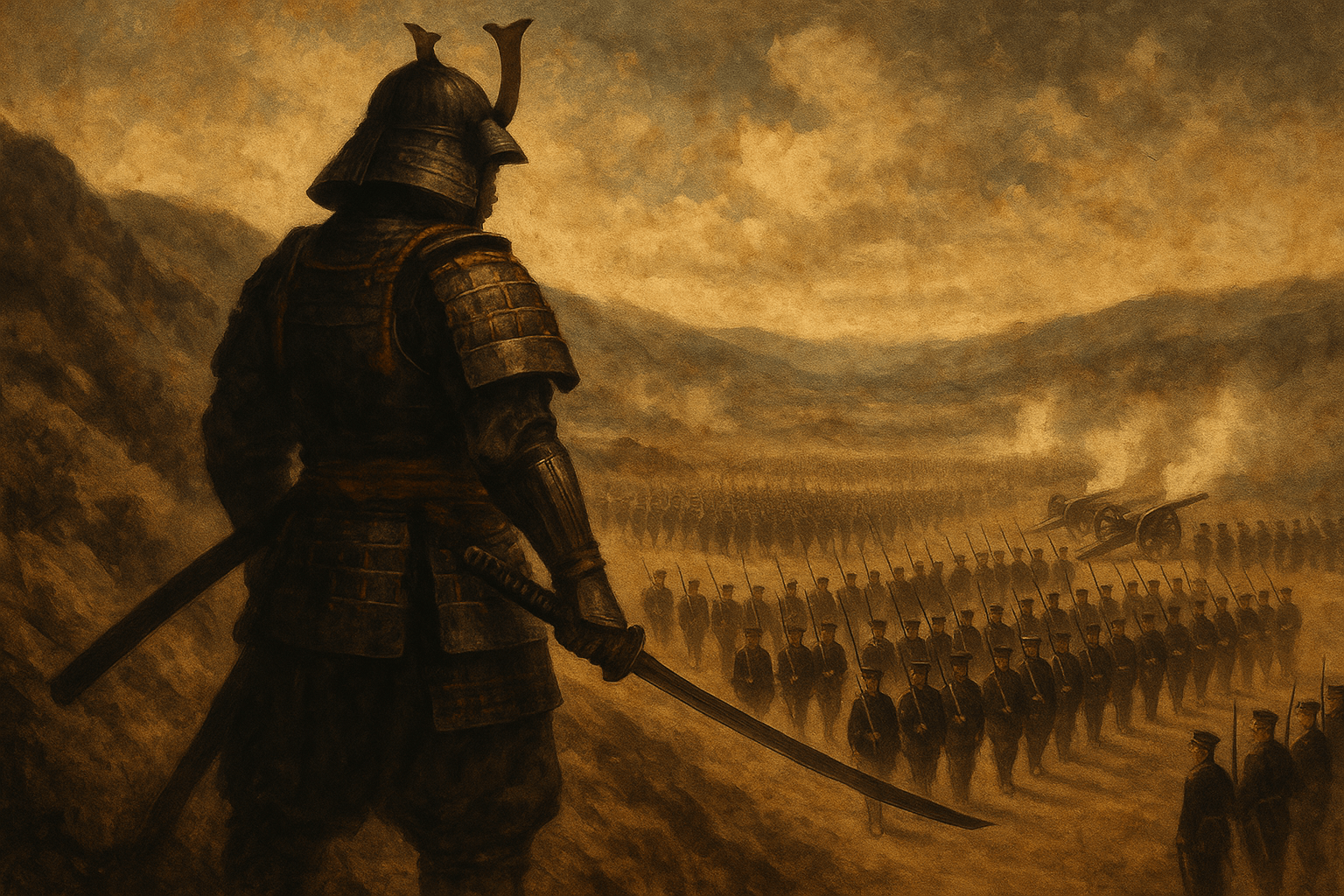

This was not a fight between flintlock rifles and swords, as Hollywood might imagine. Saigō’s army was well-equipped with modern rifles and artillery. The crucial difference lay elsewhere. The samurai rebels were fighting for honor, a cause, a way of life. They were a regional force with finite supplies and no way to replenish them.

The Imperial Japanese Army they faced was the full expression of the Meiji state. It was a national, conscripted force with superior numbers, overwhelming artillery, and the support of an industrial supply chain. It had factories producing ammunition, railways to move troops, and telegraphs for communication. The Imperial Army was fighting not just with guns, but with the entire apparatus of a modern nation-state—the very state Saigō had helped to build.

After a failed siege of Kumamoto Castle, the rebellion was slowly and systematically crushed over several months. The samurai’s initial advantages in skill and morale were ground down by the relentless logistics of modern warfare.

The Last Stand at Shiroyama

By September 1877, Saigō and his last 400-500 followers were cornered on Shiroyama, a hill overlooking Kagoshima. They were surrounded by 30,000 Imperial troops. Out of ammunition and food, there was no hope of victory. There was only the choice of how to die.

In the pre-dawn hours of September 24th, Saigō’s men, having spent the night drinking sake and bidding farewell, made their final charge. Armed with swords and spears, they crashed into the Imperial lines in a final, glorious, and suicidal display of bushidō. Saigō was grievously wounded in the hip and thigh. According to the most accepted accounts, he was carried to a secluded spot where he committed seppuku (ritual suicide), fulfilling the ultimate samurai code.

The death of Saigō Takamori and the crushing of the Satsuma Rebellion marked the definitive end of the samurai as a military and political force in Japan.

A Tragic Hero’s Legacy

Despite rebelling against the Emperor, Saigō became a revered figure in Japanese history. The public saw him not as a traitor, but as a tragic hero who embodied traditional virtues of sincerity and self-sacrifice in the face of a cold, calculating new world. He was the “real” last samurai, not because he was the last to fight, but because he represented the spirit of an age that had to die for a new Japan to be born.

In a final, telling irony, the same Meiji government that had crushed him posthumously pardoned him in 1889. Today, one of the most famous statues in Tokyo’s Ueno Park is not of a politician or an admiral, but of Saigō Takamori, walking his dog—a testament to the enduring power of his complex, tragic, and truly Japanese story.