On a cold All Hallows’ Eve in 1517, a German monk named Martin Luther nailed a document to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg. This document, his “Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences”, better known as the 95 Theses, was a scholarly protest against the Church’s practice of selling spiritual pardons. In any other era, this act of academic defiance might have sparked a local debate, been summarily condemned by a bishop, and then faded into the dusty archives of history. But this was not any other era. Luther’s act coincided with a technological revolution that would turn the spark of his protest into a continent-spanning inferno: the printing press.

A World of Whispers and Parchment

To understand the explosive impact of the printing press, we must first picture the world before it. For centuries, information moved at the speed of a horse or a ship. Books were precious, rare objects, painstakingly copied by hand by scribes, usually monks in monasteries. A single copy of the Bible could take a scribe more than a year to produce, making it as expensive as a small farm.

This reality had two profound consequences:

- Knowledge was controlled. The scarcity and cost of books meant that literacy and learning were the exclusive domain of the elite—the clergy and the nobility. The Catholic Church was the gatekeeper of information, particularly religious knowledge.

- Communication was centralized. The Church controlled the narrative. Sermons, religious art, and the Latin Mass were the primary means of communicating with the largely illiterate populace. Dissenting ideas had no efficient way to spread beyond a small, local area.

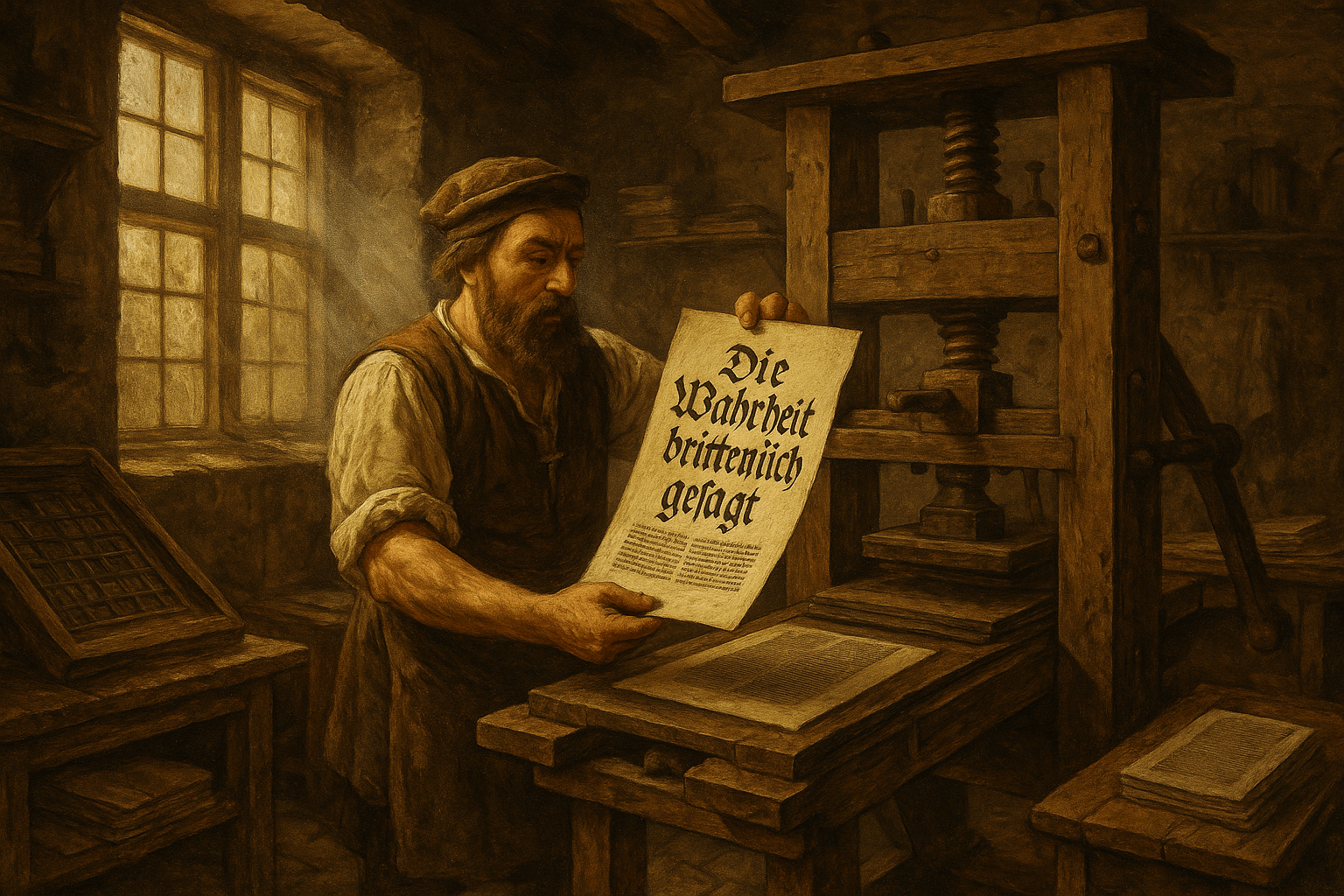

When Johannes Gutenberg perfected his movable-type printing press around 1440, he shattered this reality. Suddenly, texts could be reproduced with incredible speed, accuracy, and at a fraction of the cost. A single press could churn out hundreds of pages a day, eclipsing the annual output of an entire scriptorium. The information age had begun, and the world was unprepared for its consequences.

The Spark Becomes a Media Event

Martin Luther initially wrote his 95 Theses in Latin, the language of scholars. He intended to start a formal, academic debate. He wasn’t trying to start a revolution. But history had other plans. Someone—the identity is lost to history—saw the potential of Luther’s words, translated them from Latin into vernacular German, and brought them to a printer.

This was the critical moment. The printing presses of Leipzig, Nuremberg, and Basel began producing copies of the Theses. Within two weeks, they had spread throughout Germany. Within two months, they were across Europe. By 1520, it’s estimated that some of Luther’s key reformist tracts had sold over 300,000 copies. This was a communications phenomenon unlike anything the world had ever seen. The 95 Theses had gone viral.

The printing press allowed Luther’s message to bypass the Church’s established channels of control. Bishops and cardinals could no longer simply silence a dissenting voice with a quiet order. The ideas were already out, circulating among merchants, artisans, and nobles in their own language.

The Power of the Pamphlet

The press didn’t just spread the 95 Theses; it gave birth to a new and powerful weapon in this burgeoning war of ideas: the pamphlet. Pamphlets were short (often 8-16 pages), cheap, and written in plain, forceful German. They were the blogs and social media posts of the 16th century, designed for maximum impact and shareability.

Luther proved to be a master of this new medium. He was a prolific writer, churning out sermons, essays, and polemics that were quickly printed and distributed. Works like To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation and On the Freedom of a Christian laid out complex theological arguments in language that ordinary people could understand. He spoke directly to the German people, fostering a sense of shared identity and grievance against what he portrayed as a corrupt, foreign-dominated Church.

The Catholic Church, accustomed to a slower, more deliberate pace, was caught completely flat-footed. While Rome deliberated and drafted lengthy bulls in Latin, Luther’s printers were flooding the market with accessible, passionate, and persuasive content. By the time the Church mounted a significant print-based counter-attack, the Reformation had already taken root.

A Picture is Worth a Thousand Words (Especially if You Can’t Read)

The Reformation’s media war wasn’t fought only with words. The printing press also enabled the mass production of woodcut illustrations. This was a game-changer in a society where less than 10% of the population was literate.

Artists like Lucas Cranach the Elder, a close friend of Luther, created powerful visual propaganda. His woodcuts depicted the Pope as the Antichrist, wearing the triple crown of the Papacy but shown as a monster emerging from the jaws of Hell. In contrast, Luther was often portrayed as a saint, guided by the Holy Spirit. These stark, simple, and often crude images communicated the core message of the Reformation instantly and emotionally, reaching an audience that the densest theological pamphlet never could.

Shattering Christendom, Forging a New World

The ultimate impact of the printing press was the permanent shattering of the religious unity of Western Christendom. Before print, the Church could contain heresy. After print, it was impossible.

Luther’s German translation of the New Testament, published in 1522, became an instant bestseller. For the first time, literate laypeople could read the Bible for themselves, in their own language, without the mediation of a priest. This principle—sola scriptura, or scripture alone—was the bedrock of the Reformation, and it was a principle made tangible by the printing press. It empowered individuals to interpret God’s word for themselves, leading to a flowering of new Protestant denominations, from Lutheranism to Calvinism and beyond.

The press created a public sphere for religious debate that the Pope could not control. It turned a German monk’s grievances into a European movement, mobilizing popular support and pressuring political leaders to break with Rome. The Reformation was a complex event driven by deep theological, political, and social currents, but it was the printing press that acted as the bellows, fanning the flames until they engulfed a continent.

In the end, Luther’s hammer blow on the church door was the sound that began the Reformation. But it was the relentless, clanking rhythm of the printing press, churning out pages by the thousand, that broadcast its message to the world.