What is a Potlatch? More Than Just a Feast

To understand why Canada went to such lengths to destroy it, we must first understand what the potlatch truly is. Far from being the simple “party” that colonial officials dismissed it as, the potlatch is one of the most sophisticated and vital institutions for numerous First Nations, including the Kwakwakaʼwakw, Nuu-chah-nulth, Haida, Tsimshian, and Nuxalk, among others.

At its heart, a potlatch is a formal ceremony hosted by a leader or chief to mark a significant public event. These events could include births, deaths, adoptions, weddings, or the raising of a totem pole. The host chief would invite neighbouring nations and leaders to witness the proceedings. But the ceremony’s function went far beyond celebration. It was a complex system that upheld their entire societal structure:

- Governance and Law: Potlatches were the primary venue for validating spiritual and political authority. During a potlatch, rights to territories, family names, songs, and crests were publicly transferred and affirmed. The guests acted as official witnesses, and their acceptance of gifts at the end of the ceremony served as a binding contract, validating the host’s claims. It was their equivalent of a parliament, a courthouse, and a land registry office all in one.

- Economic System: In stark contrast to the European capitalist ideal of accumulating wealth, status in a potlatch-based society was gained by giving it away. A chief’s power and influence were demonstrated by the sheer volume of property—canoes, blankets, masks, food, and later, cash and consumer goods—that he could distribute among his guests. This acted as a powerful system of wealth redistribution, ensuring that resources flowed throughout the community and between nations, preventing any one group from becoming destitute.

- Cultural Transmission: The potlatch was the living library of the people. It was where oral histories were recited, sacred dances were performed, and ancestral songs were sung. It ensured that the cultural and historical knowledge of the nation was passed down intact from one generation to the next.

A Threat to Assimilation: Why Canada Banned the Potlatch

In the late 19th century, the Canadian government, under the authority of the newly created Indian Act of 1876, adopted an aggressive policy of assimilation. The goal was to eradicate Indigenous cultures, languages, and systems of government, and absorb Indigenous peoples into mainstream Euro-Canadian society. From the perspective of government officials and Christian missionaries, the potlatch was the single greatest obstacle to this goal.

They viewed the ceremony through a lens of profound cultural ignorance and prejudice:

- It was “Wasteful”: The concept of gaining status by giving away wealth was incomprehensible and antithetical to the Victorian values of thrift and capital accumulation. Missionaries and Indian Agents wrote scathing reports, claiming the potlatch kept Indigenous people in a cycle of poverty and prevented them from becoming “productive”, “civilized” farmers and labourers.

- It was “Heathen”: The spiritual elements of the potlatch, with its intricate dances and non-Christian cosmology, were condemned as immoral and pagan.

- It Undermined Canadian Authority: Most importantly, officials recognized that the potlatch was the heart of Indigenous self-governance. As long as the potlatch existed, traditional chiefs held authority, Indigenous law was respected, and the entire social fabric remained intact. To break the people, the government had to first break the potlatch.

In 1884, the government made its move. An amendment to the Indian Act was passed, reading:

“Every Indian or other person who engages in or assists in celebrating the Indian festival known as the ‘Potlatch’ or in the Indian dance known as the ‘Tamanawas’ is guilty of a misdemeanor, and shall be liable to imprisonment…”

The war on culture had been codified into law.

Resistance and Resilience: Keeping Culture Alive in Secret

The Potlatch Ban had a chilling effect. Participation could lead to prison sentences of two to six months. Indian Agents were empowered to confiscate all masks, blankets, and sacred regalia associated with the ceremony. But culture is not so easily extinguished.

For the next 67 years, First Nations engaged in a courageous campaign of cultural resistance. They adapted, defied, and persevered in countless ways:

- Going Underground: Potlatches were moved to remote, hard-to-reach locations, away from the watchful eyes of the Indian Agent.

- Creative Disguises: Ceremonies were sometimes held under the guise of Christian holidays like Christmas and Easter or secular ones like the 4th of July, with the gift-giving portion disguised as a more “acceptable” exchange of presents.

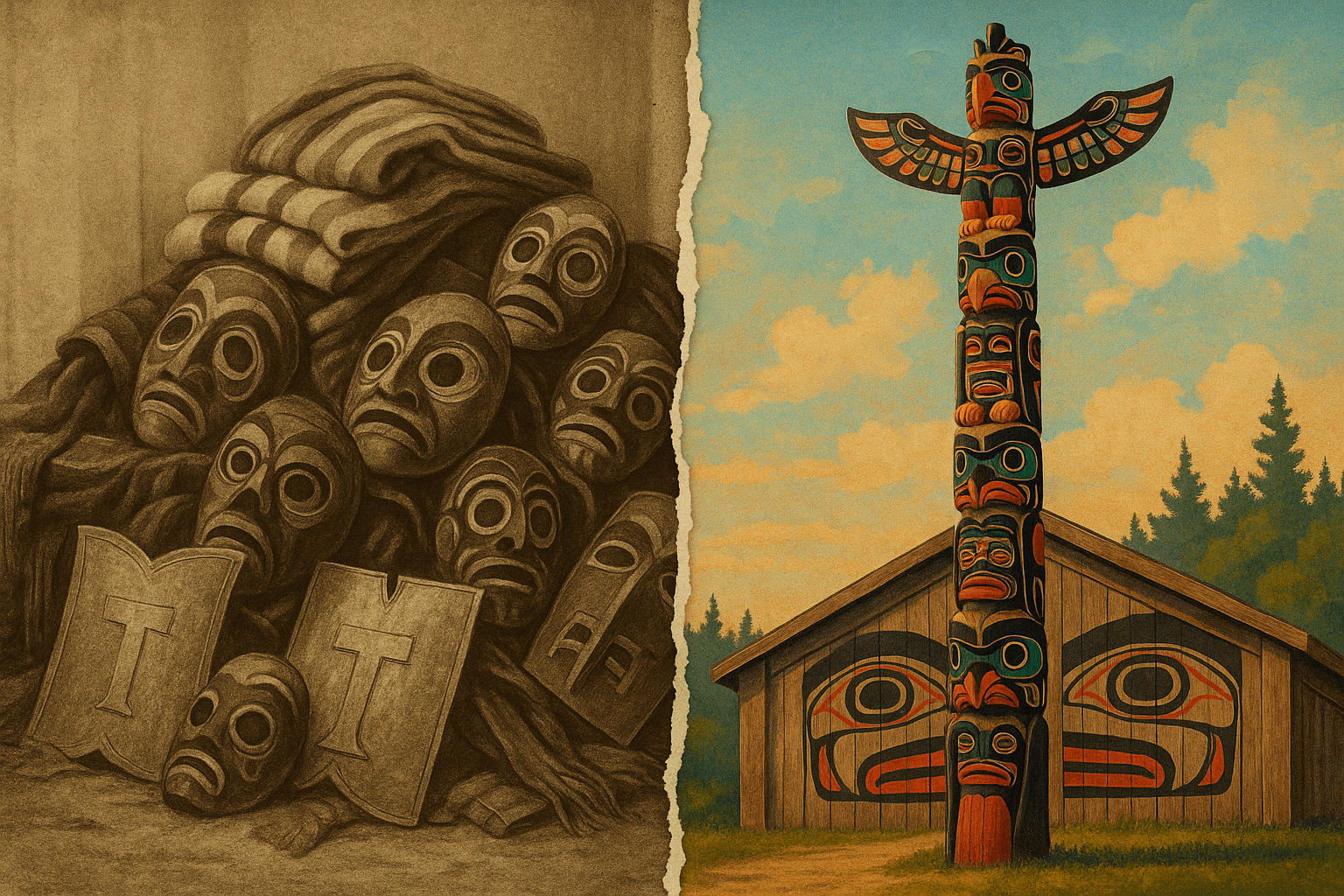

- The Cranmer Potlatch: In 1921, on Village Island, Kwakwakaʼwakw Chief Dan Cranmer hosted one of the largest potlatches on record, directly defying the law. When authorities found out, they arrested 45 participants. In a cruel ultimatum, 22 were imprisoned, while 23 others were given suspended sentences on the condition that they “voluntarily” surrender their potlatch regalia. Hundreds of priceless, sacred items—masks, rattles, headdresses, and more—were confiscated. These cultural treasures were then sold off to museums and private collectors across North America and Europe.

The Cranmer Potlatch became a symbol of both the devastating cultural loss inflicted by the ban and the unyielding spirit of those who refused to let their traditions die.

The Repeal and the Long Road Home

The Potlatch Ban was quietly dropped from a revised Indian Act in 1951. There was no grand announcement or apology. The government simply acknowledged that the law had been largely ineffective and impossible to enforce. But the damage was done. Generations had grown up under the threat of imprisonment for practicing their culture. The continuous chain of knowledge transfer had been fractured.

In the decades since, First Nations have worked tirelessly to revive the potlatch and heal the wounds of the ban. A crucial part of this healing has been the fight for repatriation—the return of their confiscated sacred items. The U’mista Cultural Centre in Alert Bay, B.C., was established in 1980 with the explicit purpose of housing the regalia returned from the Cranmer Potlatch. Its name, U’mista, means “the return of something important.”

Today, the sounds of singing and drumming once again echo in coastal longhouses. The potlatch is being practiced openly, a powerful testament to the resilience of a people who refused to be erased. It is more than just a revival of tradition; it is an assertion of sovereignty, a rebuilding of nations, and a profound act of decolonization in a country still grappling with its colonial past.