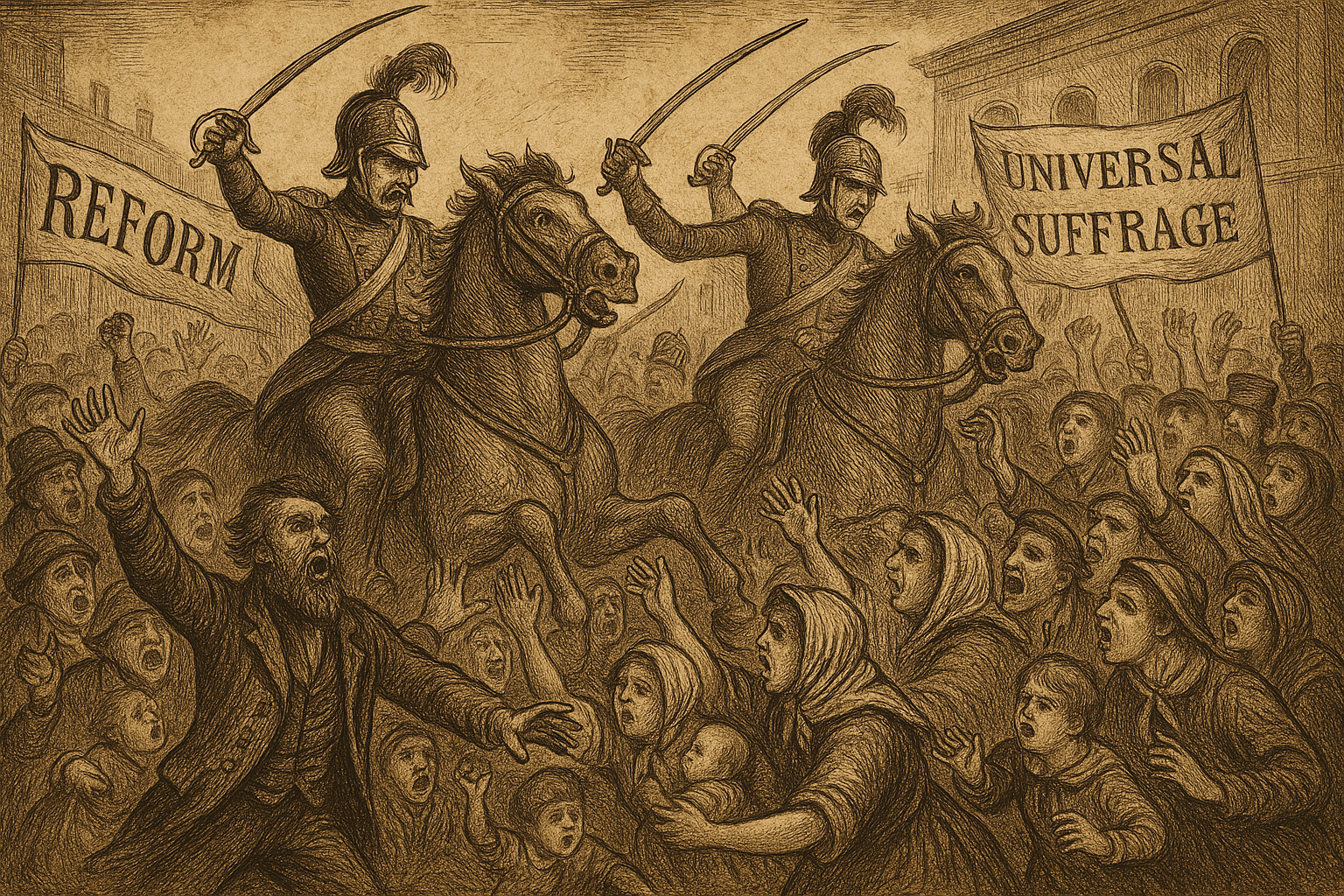

On the morning of August 16, 1819, St. Peter’s Field in Manchester was a sea of people. As many as 60,000 men, women, and even children had poured in from surrounding towns, marching in disciplined, peaceful columns. They came dressed in their Sunday best, carrying vibrant banners with slogans like “Universal Suffrage”, “Reform”, and “No Corn Laws.” The atmosphere was one of a festival, a grand day out with a profound purpose: to demand a voice in their own government. But by the end of the day, this field of hope would be a field of slaughter, and its name would be forever seared into the nation’s memory as a byword for state-sanctioned brutality.

A Nation on the Brink of Change

To understand the tragedy of Peterloo, we must first understand the Britain of 1819. The country was reeling from the economic fallout of the Napoleonic Wars. A post-war depression led to mass unemployment, particularly in the new industrial heartlands of the north. To make matters worse, the government, dominated by wealthy landowners, had passed the Corn Laws in 1815. These laws placed heavy tariffs on imported grain, keeping the price of bread artificially high to protect the profits of landowners, while the urban poor starved.

This economic misery was compounded by political powerlessness. Great industrial cities like Manchester, which had exploded in size, had no Members of Parliament (MPs) to represent their interests. Meanwhile, “rotten boroughs”—depopulated, ancient constituencies sometimes with only a handful of voters—sent MPs to London. The right to vote was exclusive, tied to property ownership, leaving the vast majority of working-class people entirely disenfranchised. Inspired by the ideals of the French Revolution, a growing radical movement demanded change. They called for universal male suffrage, annual parliaments, and a secret ballot.

The Great Meeting on St. Peter’s Field

The gathering on August 16th was organized to be the largest and most impressive demonstration of the reform movement’s strength. The guest of honor and main speaker was Henry “Orator” Hunt, a charismatic leading figure in the radical movement. The organizers stressed non-violence; attendees were explicitly instructed to come “armed with no other weapon but that of a self-approving conscience.”

As the vast, orderly crowd listened to the opening speeches, the local magistrates watched anxiously from a nearby house. They were not landowners from the distant gentry; they were local industrialists and businessmen who saw this enormous gathering of the working class not as a peaceful protest, but as the beginning of a revolutionary uprising. Gripped by fear, they made a fateful decision. They issued a warrant for the arrest of Henry Hunt and declared the meeting illegal by reading the Riot Act—though it’s doubtful more than a handful of people in the dense, noisy crowd could have heard it.

The Charge of the Sabre

To execute the arrest, the magistrates first dispatched the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry. This was a volunteer cavalry force, a part-time militia composed of local factory owners, merchants, and their sons—men who held the reformers and their cause in contempt. As the Yeomanry trotted into the crowd, they quickly became stuck, surrounded by the sheer density of the protesters.

In the confusion and panic, swords were drawn. Seeing the Yeomanry floundering, William Hulton, the chairman of the magistrates, ordered in the 15th Hussars, a regular army cavalry regiment, to disperse the crowd.

What followed was mayhem. The professional Hussars, followed by the enraged Yeomanry, charged into the trapped mass of people. With sabres flashing, they hacked and slashed their way through the crowd. Men, women, and children were cut down or trampled by the terrified throng and the charging horses. Within 20 minutes, the field was cleared, but it was left littered with the dead and maimed. One victim, a two-year-old boy named William Fildes, was knocked from his mother’s arms and killed. Another, John Lees, was a veteran who had fought for Britain at the Battle of Waterloo, only to be killed by his own countrymen in a Manchester field.

In total, an estimated 18 people were killed and over 600 were severely injured.

The Aftermath: Repression and Resistance

News of the “Peterloo Massacre”—a bitterly ironic name coined by a journalist to contrast the slaughter of civilians with the soldiers’ glorious victory at Waterloo four years earlier—sparked outrage across the country. But the government’s response was not justice, but repression.

The magistrates and Yeomanry were officially praised by the Prince Regent for their “prompt, decisive, and efficient measures for the preservation of the public peace.” Henry Hunt and the rally organizers, meanwhile, were arrested, tried, and jailed for sedition.

Parliament quickly passed the infamous “Six Acts”, a legislative package designed to crush the radical movement. These laws drastically curtailed public meetings, cracked down on reformist newspapers, and increased the power of the state to prosecute dissenters. The message was clear: protest would not be tolerated.

The Long Shadow of Peterloo

The government’s heavy-handed response, however, completely backfired. Peterloo did not kill the cause of reform; it made it a holy crusade. The massacre became a powerful symbol of tyranny and a rallying cry for democracy that would echo for generations.

- It exposed the brutal chasm between the ruling elite and the working people of Britain.

- It created martyrs, whose stories fueled the anger and determination of reformers.

- It directly led to the founding of the Manchester Guardian newspaper (today, The Guardian) in 1821, established by a group of non-conformist businessmen to campaign for parliamentary reform.

The road to democracy remained long and difficult. While the Great Reform Act of 1832 was a small step forward, it was the subsequent Chartist movement and decades of further struggle that eventually won the rights the Peterloo protesters had demanded. The massacre served as a foundational story for these later movements, a stark reminder of what was at stake.

Today, the Peterloo Massacre stands as a crucial, if brutal, turning point in British history. It was a day when a peaceful call for representation was met with swords and hooves, but it ignited a fire for change that could not be extinguished. It is a vital chapter in the story of how ordinary people fought, and died, for the democratic rights we often take for granted.