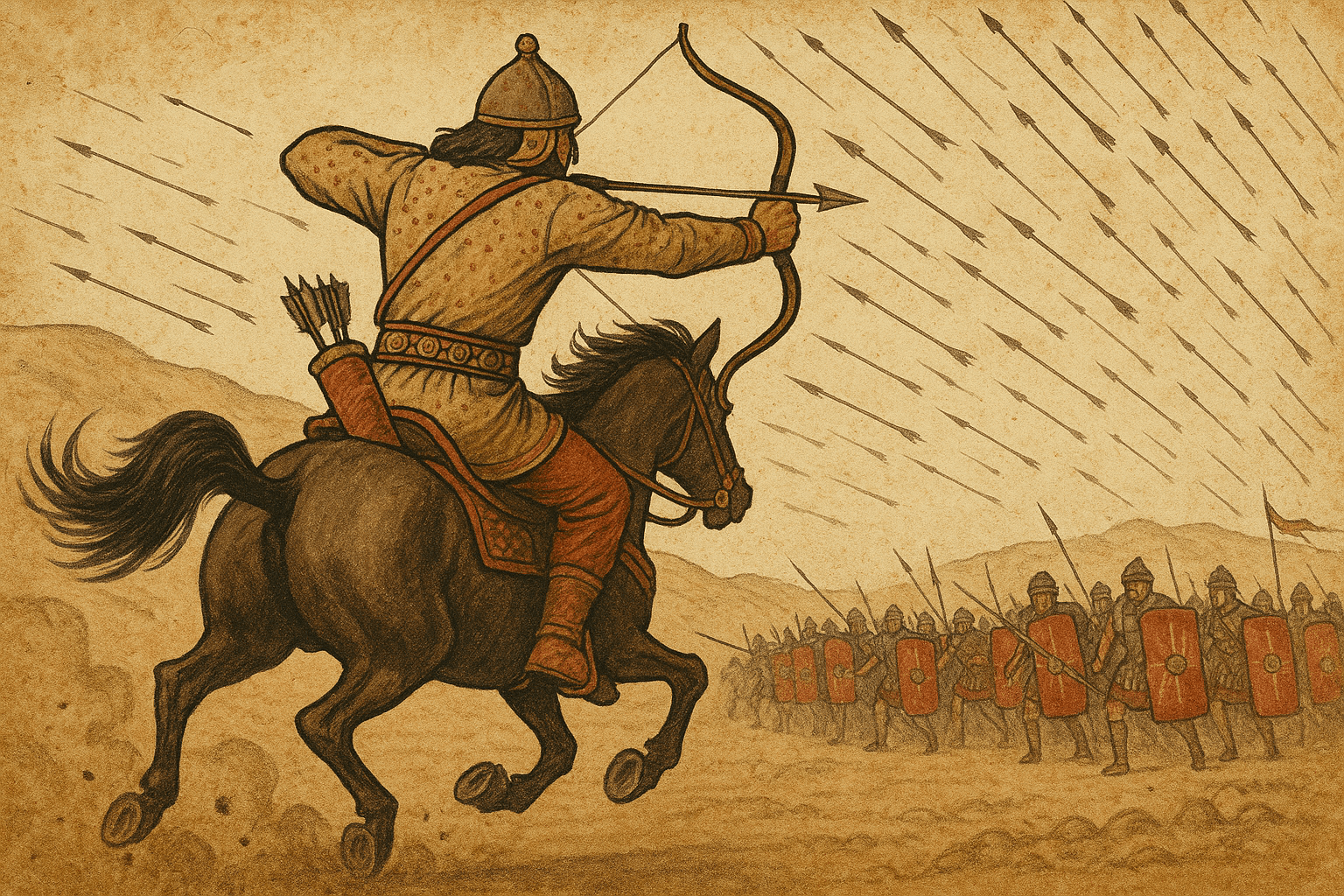

Imagine a chaotic battlefield on the sun-scorched plains of Mesopotamia. A powerful, disciplined army of Roman legionaries advances, their shields locked and their short swords ready. Before them, a seemingly disorganized horde of horsemen breaks and flees in apparent panic. The Romans, sensing victory, break a formation to give chase. It’s a fatal error. As the legionaries surge forward, the fleeing horsemen do something extraordinary: they twist in their saddles, and at a full gallop, unleash a devastating volley of arrows back into the pursuing ranks. This is the Parthian Shot, a tactic so effective, so terrifying, and so iconic that it has echoed through history and even entered our modern language.

Who Were the Parthians?

Before we dissect their signature tactic, it’s essential to understand the people behind it. The Parthian Empire (c. 247 BC – 224 AD) was a major Iranian political and cultural power that dominated the region of modern-day Iran and its surrounding territories. Emerging from the Parni, a nomadic Scythian tribe from Central Asia, the Parthians inherited a deep-rooted equestrian culture. Horsemanship and archery weren’t just military skills; they were a way of life, learned from childhood.

Their military was a direct reflection of this heritage. Unlike the infantry-centric armies of Rome, the Parthian force was built on two types of cavalry:

- Horse Archers: The backbone of the army. These were lightly armored, incredibly mobile riders mounted on swift steeds. Their primary weapon was the powerful composite bow, a masterpiece of engineering made from wood, sinew, and horn, capable of launching arrows with enough force to pierce Roman armor.

- Cataphracts: The heavy cavalry. These were the shock troops, knights in shining armor centuries before their European counterparts. Both rider and horse were completely encased in scale or mail armor, and they wielded a massive lance called a kontos. They were the immovable object to the horse archers’ irresistible force.

This dual-cavalry system allowed the Parthians to execute a flexible, hit-and-run style of warfare that baffled their more conventional enemies.

Anatomy of a Winning Retreat

The Parthian Shot was not a simple maneuver; it was a sophisticated system of psychological warfare, expert skill, and tactical brilliance. It can be broken down into three distinct phases that worked in a devastating cycle.

Phase 1: The Lure

It began with harassment. The horse archers would ride in close to the enemy, peppering their lines with arrows from a safe distance. They were a frustrating, elusive target. When the enemy, goaded beyond endurance, launched a charge, the Parthians would feign a retreat. This was a carefully orchestrated deception. They would turn and ride away, appearing to be in a disorganized rout. To a commander like the Roman Marcus Licinius Crassus, this was an irresistible opportunity to crush a fleeing foe and win a decisive victory.

Phase 2: The Turn and Fire

This is the iconic moment. As the enemy pursued, confident and often breaking their tight defensive formation, the Parthian horse archers would execute their legendary feat. At a full gallop, they would rise in their stirrups, twist their entire torso to the rear, and loose a volley of arrows into the surprised faces of their pursuers. The physical skill required for this cannot be overstated. It demanded incredible core strength, balance, and the ability to aim a powerful bow while controlling a galloping horse, all without the benefit of a rigid saddle or extensive stirrups as we know them today.

Phase 3: The Relentless Cycle

The Parthian Shot was not a one-time trick. After firing, the archers would face forward and continue their “retreat”, giving them time to nock another arrow. They would repeat this process again and again, whittling down the enemy with each volley. The pursuing army was caught in a terrible dilemma: if they continued the chase, they would suffer continuous casualties. If they stopped to reform, the Parthians would simply halt out of range, regroup, and begin harassing them anew. This created a “kill zone” that moved with the army, a relentless storm of arrows from which there was no escape.

Carrhae, 53 BC: The Ultimate Case Study

Nowhere was the devastating effectiveness of this doctrine more apparent than at the Battle of Carrhae. The overconfident Roman Triumvir, Marcus Licinius Crassus, marched seven legions—over 40,000 elite troops—into Parthian territory seeking glory and conquest. He was met by a far smaller Parthian army under the brilliant general Surena.

Crassus made the critical mistake of allowing himself to be drawn into open, flat terrain, perfect for cavalry. Surena’s 9,000 horse archers and 1,000 cataphracts went to work.

The Romans formed their famous testudo (tortoise) formation, locking their shields overhead and to the sides to create a mobile fortress against the arrow storm. But the power of the Parthian composite bows was too great. Arrows pierced shields, limbs, and armor. Even more terrifying for the Romans was the Parthian logistics. Surena had brought a baggage train of over 1,000 camels loaded with nothing but arrows, ensuring his archers had a virtually inexhaustible supply.

When Roman formations wavered or tried to sally out, Surena unleashed his cataphracts. These armored behemoths crashed into the weakened Roman lines with irresistible force, shattering their cohesion and driving them back into the arrow storm. The horse archers were the hammer, and the cataphracts were the anvil. Caught between them, the Roman army was systematically dismantled.

The result was one of Rome’s most humiliating defeats. Over 20,000 Romans were killed and another 10,000 captured, including Crassus himself, who was later executed. The cherished legionary standards, the symbols of Roman pride, were lost to the Parthians.

The Lasting Legacy of a Parting Shot

The Battle of Carrhae cemented the reputation of the Parthian military and its signature tactic. It demonstrated that the Roman legion, while supreme in close-quarters infantry combat, was vulnerable to a different kind of warfare. The Romans eventually learned from this, incorporating more auxiliary cavalry and archers into their own armies to counter the threat.

The Parthian tactic, while perfected by them, was a staple of steppe warfare, used by peoples like the Scythians, Huns, and later the Mongols, who would use similar feigned retreats to conquer much of the known world. But it was the Parthians who made it legendary in the classical West.

Today, the phrase “a Parthian shot” lives on in our language, meaning a final, sharp, and often wounding remark made as one is leaving. It’s a fitting tribute to a military maneuver that was, for the enemies of the Parthian Empire, the most devastating parting gift of all.