From Persian Refugees to Indian Pioneers

The Parsi story begins over a millennium ago with an escape. Fleeing religious persecution following the Arab conquest of Persia in the 7th century, a small group of Zoroastrians set sail, eventually landing on the coast of Gujarat, India. Legend tells of their meeting with the local Hindu ruler, Jadhav Rana, who presented them with a bowl of milk filled to the brim, symbolizing a land with no room for newcomers. The resourceful Parsi leader responded by dissolving a spoonful of sugar into the milk without spilling a drop, promising that his people would sweeten the society, not displace it.

True to their word, the Parsis assimilated peacefully. They adopted the local language (Gujarati) and dress (the sari for women) while diligently preserving their ancient faith. For centuries, they lived primarily as farmers, weavers, and small-scale artisans, earning a reputation for honesty and diligence that would become their most valuable asset in the centuries to come.

Seizing the Winds of Change: The Rise of Parsi Shipbuilders

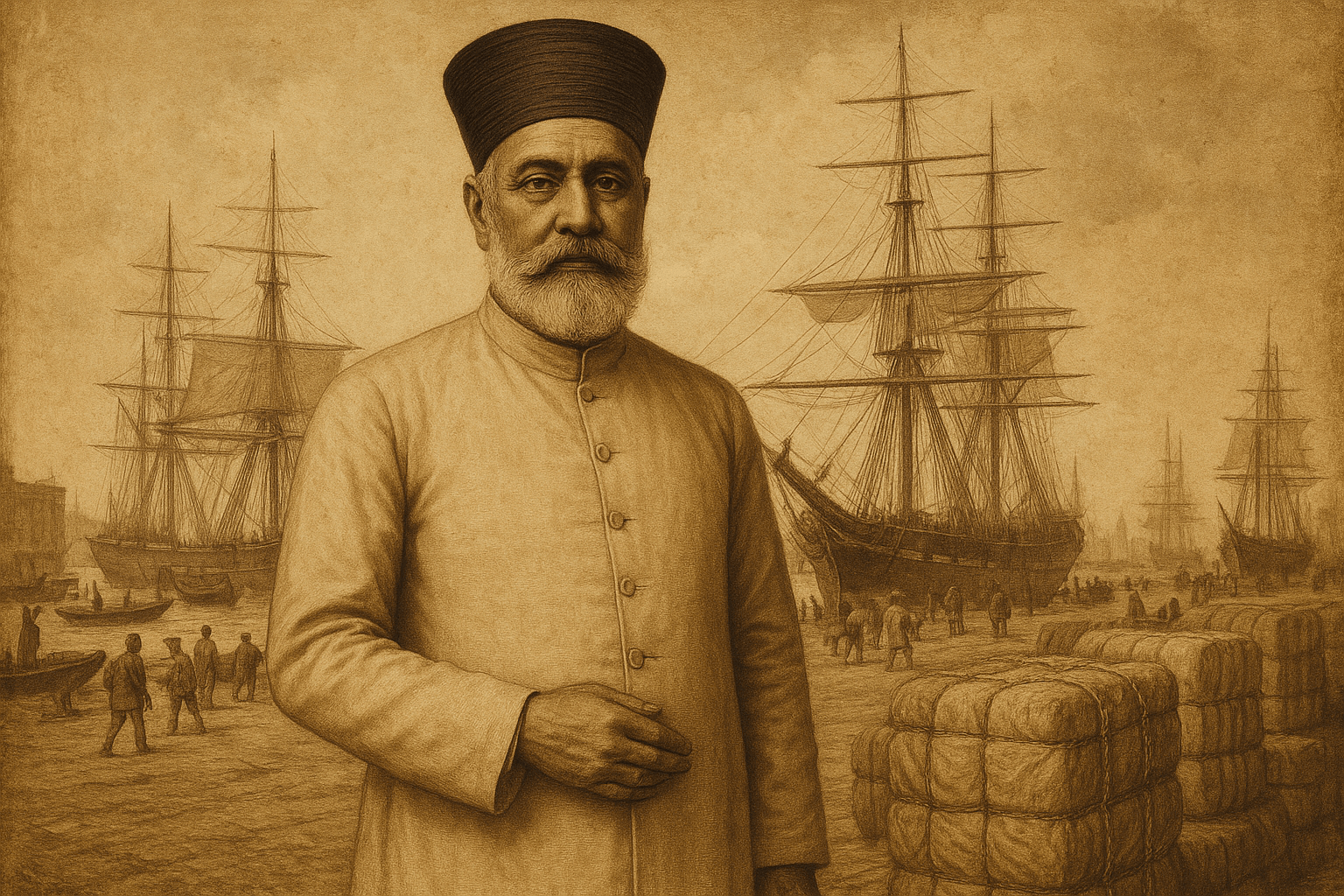

The arrival of European trading companies, particularly the British East India Company, was the catalyst that transformed the Parsi community’s fortunes. When the British shifted their main western Indian base from Surat to Bombay (now Mumbai) in the 17th and 18th centuries, the Parsis followed, recognizing a new horizon of opportunity.

One of their first and most significant contributions was in shipbuilding. Unlike many Hindu communities, Parsis had no religious taboos against crossing the ocean or working with “unclean” materials, making them ideal partners for the maritime-focused British. The most legendary name in this field is the Wadia family. In 1736, the East India Company lured the master shipbuilder Lowellji Nusserwanji Wadia to Bombay to manage a new shipyard. This began a dynastic legacy that would last for over 150 years.

The Wadia shipyards didn’t just build ships; they built masterpieces. Using Malabar teak, a wood far more durable and resistant to shipworm than European oak, they constructed over 350 vessels for clients ranging from the British Royal Navy to merchants across the globe. Famous ships like the HMS Trincomalee (launched in 1817 and now the oldest British warship still afloat) and the HMS Minden (aboard which Francis Scott Key is said to have penned “The Star-Spangled Banner”) were testaments to Parsi craftsmanship. These “Wadia-builts” became the backbone of British naval power in the East.

Kings of Commerce: The Cotton and Opium Trades

While shipbuilding laid the foundation, it was the mastery of global commodity trades that cemented Parsi economic dominance. As trusted intermediaries who were fluent in English, Gujarati, and Persian, they were perfectly positioned to bridge the gap between British capital and Indian production.

The American Civil War (1861-1865) proved to be a pivotal moment. With cotton supplies from the American South cut off, the textile mills of Lancashire, England, faced a “cotton famine.” Parsi merchants like the legendary Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy and the Petit family moved decisively to fill this void. They financed, sourced, and shipped vast quantities of Indian cotton, accumulating immense fortunes and establishing Bombay as a global cotton hub.

However, no discussion of Parsi merchant history is complete without mentioning the controversial but historically crucial opium trade. In the 19th-century triangular trade route—where Indian opium was sold in China to finance British purchases of tea—Parsi merchants were key players. They owned the ships, insured the cargo, and acted as the primary agents for the British. Figures like Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy, who started his life in poverty, built the foundation of his immense wealth through the opium trade with China. While ethically complex by today’s standards, this trade was the engine of global commerce at the time, and it funneled unprecedented capital into Bombay, capital that the Parsis would soon reinvest in their adopted city.

Building a Metropolis: The Parsi Imprint on Mumbai

What truly sets the Parsi merchants apart is what they did with their wealth. They were not merely extractors of profit; they were city-builders and philanthropists. The fortunes made in the Canton trade and the cotton boom were systematically poured back into building the infrastructure of a modern city and civil society.

The Parsi legacy is written into the very fabric of Mumbai:

- Industry and Infrastructure: They were pioneers, establishing India’s first modern textile mills, banks, and insurance companies. The visionary Jamsetji Tata, starting with textile mills, laid the groundwork for what would become the Tata Group, India’s most respected conglomerate. His vision extended to founding the iconic Taj Mahal Palace Hotel, the Indian Institute of Science, and the country’s first major steel plant.

- Philanthropy and Education: Believing that wealth came with social responsibility, Parsis funded countless schools, hospitals, and cultural institutions. The Sir J.J. School of Art and the J.J. Hospital, both funded by Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy, remain premier institutions in the city today.

- Civic Life: They financed causeways and land reclamation projects that physically shaped the seven islands of Bombay into the unified metropolis we know today. They endowed public parks, libraries, and theatres, enriching the city’s cultural life.

From the docks they built to the industries they founded and the institutions they endowed, the Parsis transformed Bombay from a colonial outpost into India’s vibrant commercial and financial capital. Their story is a powerful testament to how a small, displaced community, armed with resilience, foresight, and a profound sense of civic duty, can leave an indelible mark on the world stage.