More Than a Myth: The Legend of “The Gilded Man”

The story of El Dorado (Spanish for “The Gilded One”) did not begin as a place, but as a person and a ceremony. The Muisca people, who inhabited the high-altitude plains of modern-day Colombia, practiced a spectacular investiture ritual for their new ruler, or zipa. This ceremony, which took place on the sacred Lake Guatavita, was the seed from which the sprawling legend grew.

According to accounts from the 16th century, the ritual was a profound act of spiritual renewal and political affirmation. The heir to the chieftainship would be stripped naked and his body covered in sticky resin, over which fine gold dust was blown until he became a living statue of gold, glimmering under the Andean sun. He was “The Gilded Man.”

He would then board a ceremonial raft, accompanied by other high-ranking chiefs and priests. As the raft was paddled to the center of the deep, circular lake, music and chanting would echo from the shores, where thousands of his people gathered. Upon reaching the middle, a profound silence would fall. The new zipa would then cast offerings of gold objects and precious emeralds—known as tunjos—into the water as a sacrifice to the gods. Finally, he would dive into the lake, washing the gold dust from his body and emerging cleansed, reborn, and officially confirmed as the leader of the Muisca people.

When the Spanish arrived, they heard whispers of this ritual from coastal tribes. Through translation, exaggeration, and their own insatiable greed, the story of a man covered in gold morphed into a city built of it. The hunt for El Dorado was on, but the conquistadors were chasing a phantom born of a misunderstood reality.

A Discovery in a Cave: The Muisca Raft Unearthed

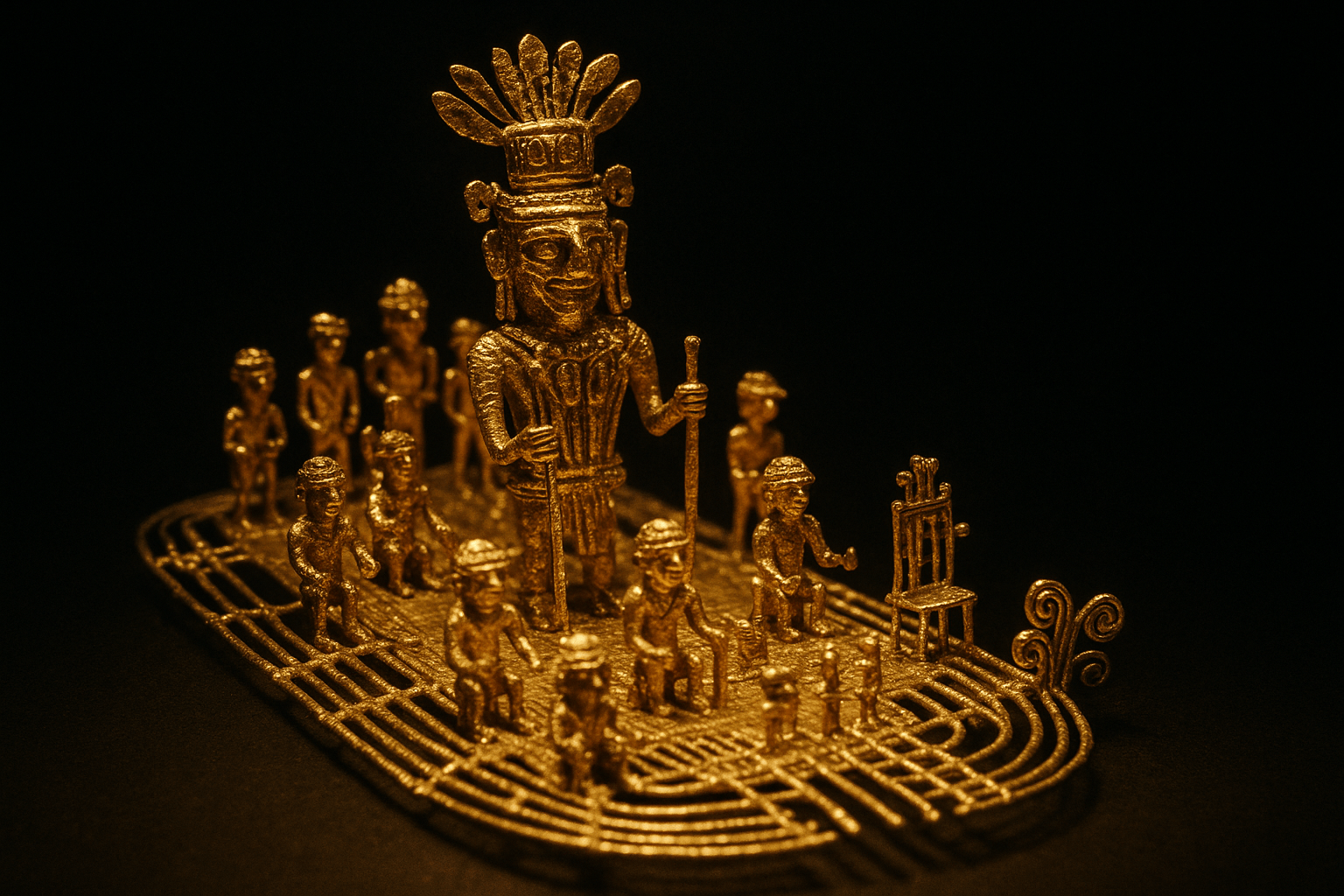

For centuries, the ceremony was just a story, a historical account. Then, in 1969, three farmers exploring a cave near the town of Pasca, Colombia, made an extraordinary discovery. Nestled inside a ceramic pot, protected from the elements for nearly 500 years, was a small, intricate golden raft. It was an almost perfect, three-dimensional depiction of the El Dorado ceremony.

Measuring just 19.5 cm long and 10.1 cm wide, the Muisca Raft is a triumph of pre-Columbian metallurgy. It was crafted from an alloy of gold and copper known as tumbaga using the sophisticated lost-wax casting technique. This method involves creating a detailed model in beeswax, encasing it in clay, and then heating the mold to melt the wax out. Molten metal is then poured into the resulting cavity, creating a precise replica of the original wax model.

The artifact depicts a prominent central figure, taller than the others and adorned with a spectacular headdress, undoubtedly the zipa. He is surrounded by ten smaller figures, likely his attendants and fellow chiefs, some holding staffs and wearing their own adornments. They all stand upon a meticulously detailed raft, frozen in the very moment of their sacred journey across Lake Guatavita. The raft is not just a piece of jewelry; it is a historical document cast in gold, a narrative scene that validates the chronicles of the Spanish and, more importantly, preserves the memory of the Muisca people’s most sacred ritual.

The Muisca: Masters of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense

To truly understand the raft, one must understand its creators. The Muisca were not a unified empire like the Inca or Aztecs but a confederation of chiefdoms that flourished on the Altiplano Cundiboyacense—the high plateaus of Colombia’s Eastern Andes. By the 15th century, they had developed a complex society based on sophisticated agriculture (growing maize, potatoes, and quinoa), expert weaving, and extensive trade networks.

One of their most valuable commodities was salt, which they mined from underground deposits and traded for goods from other regions, including the gold they used in their metalwork. But for the Muisca, gold’s value was not economic. They did not use it as currency. Instead, gold was a sacred material, imbued with divine power. Its yellow luster was associated with the creative and life-giving energy of their sun god, Sué. To the Muisca, gold was a vehicle for communicating with the divine, a physical manifestation of sacred power, not a measure of earthly wealth.

Gold, Water, and Cosmology: The Meaning of the Offering

The Muisca cosmology was deeply intertwined with their environment. The mountains, rocks, and especially the lakes (lagunas) were considered sacred portals to the spirit world. Lake Guatavita was one of the most revered, believed to be the home of the serpent goddess Bachué, the mother of all humanity.

The El Dorado ceremony was therefore an act of cosmic balance. By offering gold—the physical embodiment of the sun’s masculine, creative energy—into the sacred lake—the embodiment of the feminine, watery, and generative realm—the Muisca were renewing the primordial pact between their people and their gods. It was a reciprocal act, a “payment” to ensure the continued fertility of the land, the well-being of the people, and the legitimacy of their new leader.

When the zipa plunged into the water, he symbolically entered the spirit realm. By emerging cleansed of his golden coating, he was reborn, his authority now sanctified by the gods themselves. The ceremony was not an ostentatious display of wealth but a profound and necessary act of religious and political statecraft.

The Enduring Legacy of the Raft

Today, the Muisca Raft rests at the heart of the world-renowned Museo del Oro (Gold Museum) in Bogotá, Colombia. It stands as a silent testament to a civilization whose worldview was tragically misunderstood. The Spanish saw gold and thought only of monetary wealth, triggering a destructive quest for a city that never was.

The raft reminds us that the true treasure was not the gold itself, but the intricate culture that produced it. It transforms the legend of El Dorado from a simple tale of greed into a complex story of faith, cosmology, and identity. This small, exquisite object is more than a glimpse of El Dorado; it is a window into the soul of the Muisca people.