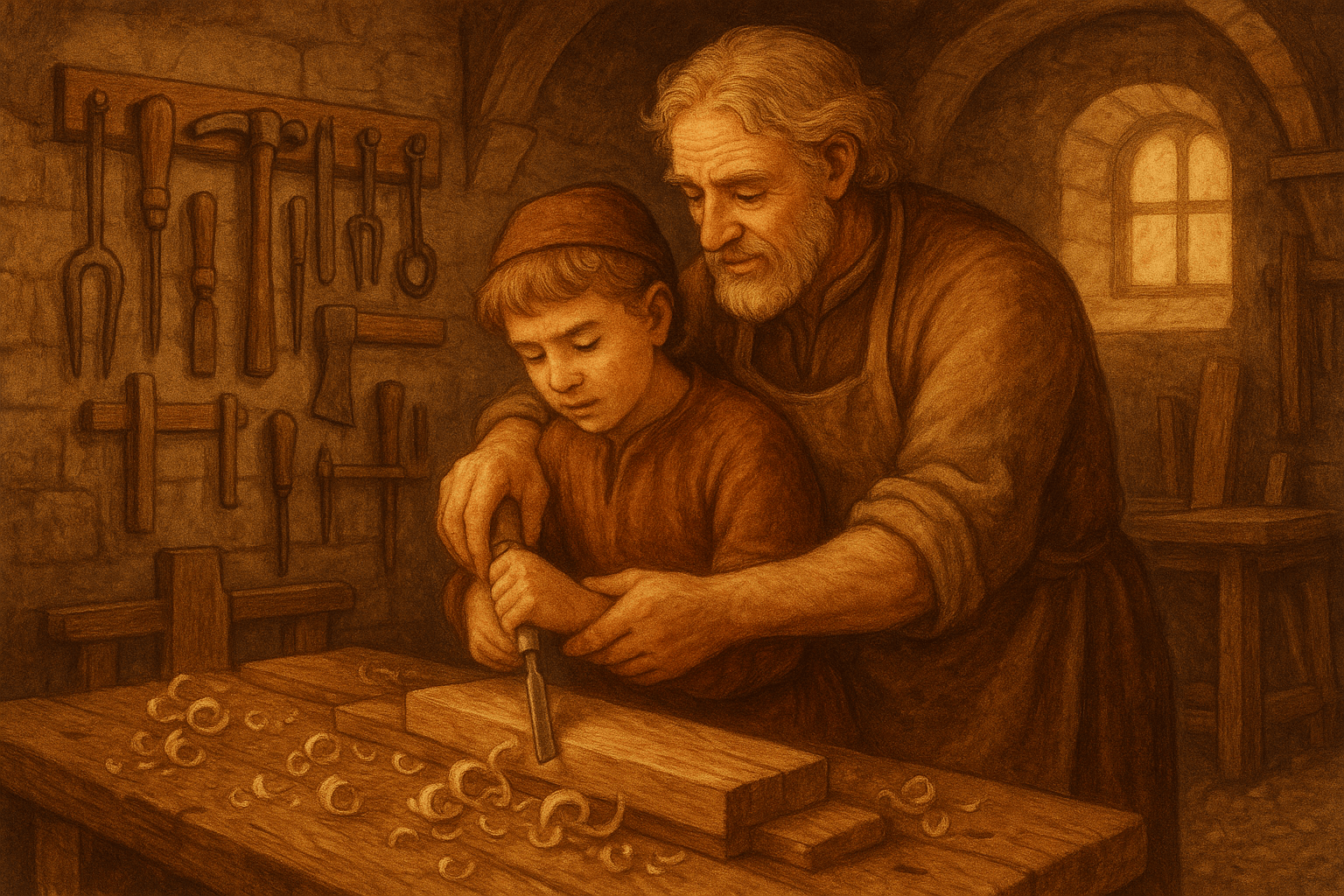

For a world largely without formal public education, apprenticeship was the only way to pass specialized skills from one generation to the next. It was a formal, structured, and legally binding journey from childhood ignorance to professional mastery.

The Binding Contract: An Indenture for Life

An apprenticeship began not with a handshake, but with a formal contract known as an “indenture.” This legal document was so named because two copies were written on a single sheet of parchment, which was then torn or cut along a jagged, or “indented”, line. The master kept one half and the apprentice’s family the other; the unique tear proved the authenticity of the contract if it was ever challenged.

These contracts were serious business and meticulously detailed the obligations of both parties. A typical indenture, which usually lasted for seven years (though terms from five to twelve years were common), would stipulate that the apprentice must:

- Obey the master and his wife (the “mistress”) in all things.

- Work diligently and faithfully.

- Safeguard the master’s trade secrets, referred to as the “art and mystery” of the craft.

- Not frequent taverns, gamble, or engage in immoral behavior.

- Not marry without the master’s permission.

In return, the master was legally bound to:

- Provide food, lodging, and clothing.

- Teach the apprentice the entirety of his craft, holding nothing back.

- Offer moral and religious guidance, acting in loco parentis (in the place of a parent).

- Sometimes, a small sum of money or a new set of tools was given to the apprentice upon completion of their term, known as their “freedom dues.”

The apprentice essentially became part of the master’s household, a hybrid of a family member, a student, and an unpaid servant.

A Day in the Life: Sweat, Toil, and Learning

Life as an apprentice was anything but glamorous. The workday began at dawn and ended at dusk, often six days a week. The first few years were typically spent on menial, back-breaking labor designed to build discipline as much as to assist the workshop. A young apprentice to a painter might spend a year just grinding pigments. A blacksmith’s apprentice would be responsible for managing the fire and cleaning the forge long before he was allowed to heat metal. A weaver’s apprentice would card wool and fetch supplies.

The workshop was a strict hierarchy. At the top was the master, the sole owner of the business. Below him were journeymen—skilled workers who had completed their own apprenticeships—and at the bottom of the pile were the apprentices. As a new apprentice, you were at the beck and call of everyone.

Living conditions were basic. An apprentice might sleep on a pallet in the attic, the corner of the workshop, or under a counter. Food was simple but usually provided in sufficient quantity to fuel a long day’s work. Discipline was harsh. The master had the legal right to physically punish his apprentice for laziness, mistakes, or disobedience. While some masters were kindly mentors, others were cruel tyrants, and a young apprentice had little recourse.

Not Just for Boys: The Forgotten Female Apprentices

While we often picture apprentices as young boys hammering away in a forge, girls and young women were also part of this system, though their opportunities were more limited. They were typically apprenticed in trades deemed “feminine.” These included:

- Textile Trades: Spinning, weaving, and especially the highly skilled and lucrative silk and embroidery trades.

- Victualing Trades: Brewing (“alewife”), baking, and other forms of food preparation.

- Domestic Crafts: Seamstressing and dressmaking.

Female apprentices were often bound to the master’s wife, the mistress of the household, who would manage these aspects of the family business. In many cases, a girl’s apprenticeship was an informal arrangement within her own family, as a daughter learned the trade she would one day inherit or bring to a marriage. Upon a master’s death, it was not uncommon for his widow, having learned the craft by his side for years, to take over the workshop and even take on new apprentices herself.

The Ladder of Success? From Apprentice to Master

The ultimate goal of the apprentice system was to create a new generation of masters. The path, however, was a narrow and difficult one.

1. Apprentice: The learning phase, lasting roughly seven years.

2. Journeyman: Upon “graduation”, the apprentice became a journeyman. The name derives from the French journée (“day”), as they were now free to travel and hire themselves out for a daily wage. This period allowed a craftsman to hone his skills, see how different masters worked, and—crucially—save money.

3. Master: To achieve the final rank, a journeyman had to gain admission to the local trade guild. This was the most challenging step. The guild, a powerful organization that controlled quality and competition, required a journeyman to prove his skill by submitting a “masterpiece” (or chef-d’oeuvre). This was a piece of work—a perfectly wrought sword, an intricate tapestry, a flawless pair of shoes—that demonstrated his total command of the craft. But skill alone was not enough. He also needed capital to set up his own workshop and pay the guild’s steep entrance fees. For this reason, many were journeymen their entire lives.

So, did the system offer social mobility? For a talented, hardworking, and lucky few, yes. A peasant’s son could theoretically become a wealthy master craftsman and a respected town citizen. In reality, the system often reinforced the existing social structure. The easiest way to become a master was to be a master’s son or to marry a master’s daughter. As the Middle Ages wore on, guilds became increasingly exclusive, making it ever harder for outsiders to climb the ladder.

The medieval apprentice system was a harsh and demanding world. It demanded the sacrifice of childhood in exchange for skill, security, and a place in the economic fabric of society. While its modern-day descendants—internships, trade schools, and residencies—are far more humane, they owe their existence to this ancient model of learning by doing, a testament to the enduring idea that true mastery is earned through years of dedicated practice.