From the Steppes to the Nile: The Origins of the Mamluks

The Mamluk system wasn’t born in a day. For centuries, Islamic rulers had relied on enslaved soldiers, often recruited from beyond the borders of the Muslim world. The practice was perfected by the Ayyubid dynasty, founded by the famous Saladin. Ayyubid sultans purchased thousands of young non-Muslim boys, primarily Kipchak Turks from the Eurasian steppes, in the slave markets of the Black Sea.

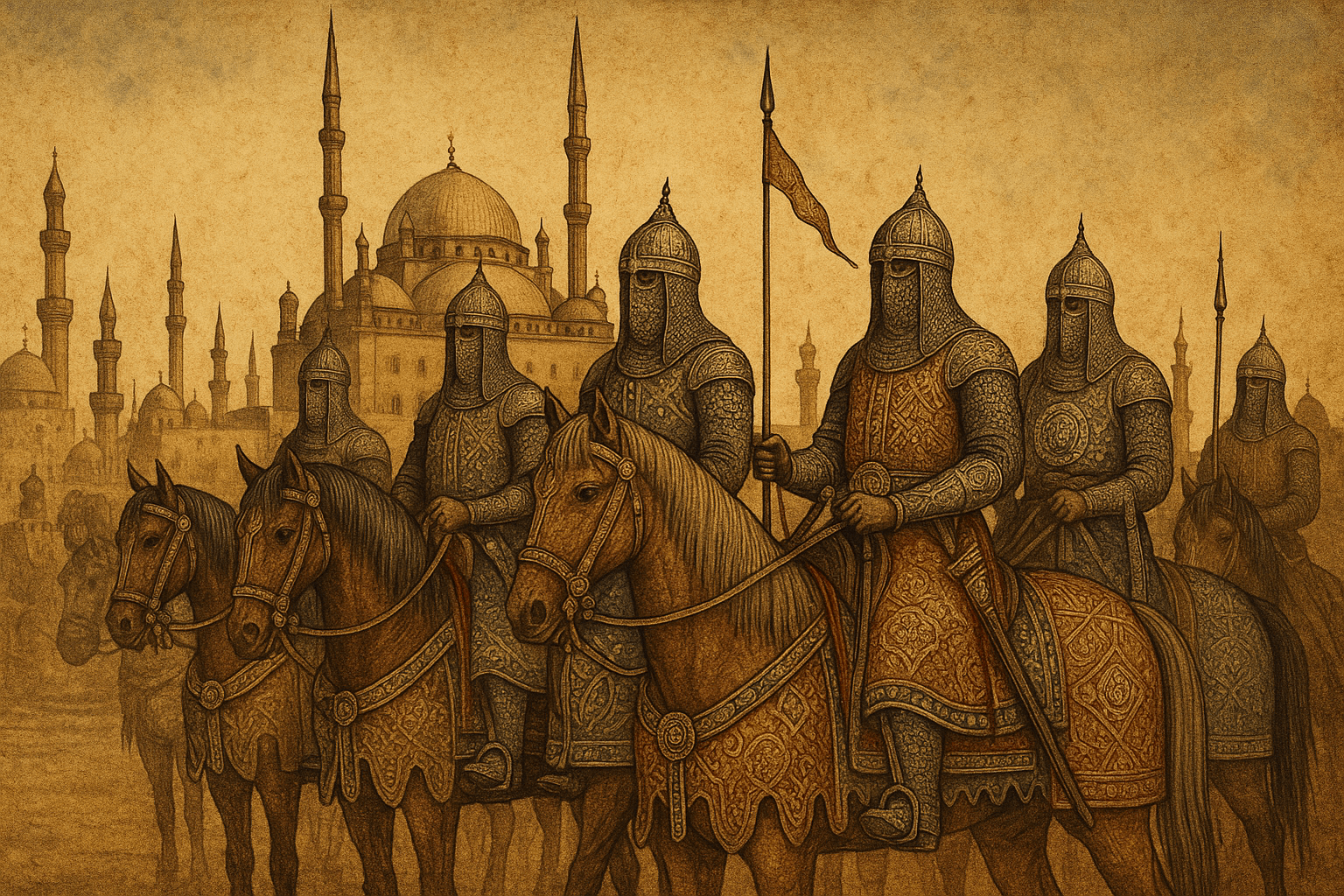

These boys were not ordinary slaves. They were brought to barracks in Cairo, converted to Islam, and subjected to a grueling and sophisticated training regimen. They learned Arabic, the Quran, and, most importantly, the arts of war—horsemanship, archery, and swordsmanship. This process, known as the furūsiyyah, forged them into an elite military caste. Their loyalty was not to a nation or a people, but to a single person: their master, the sultan or emir who had purchased and trained them. This created a powerful, insulated warrior class with no family ties to the local population, making them, in theory, the perfect loyal bodyguards.

The Seizure of Power: A Dynasty is Born

The Ayyubids created a force so effective that it eventually consumed them. By the mid-13th century, Mamluk generals held immense power within the Ayyubid military. The turning point came in 1250. Following the death of Sultan al-Salih Ayyub, his ambitious and capable widow, Shajar al-Durr (a former slave herself), conspired with the Bahri Mamluks—an elite regiment garrisoned on an island in the Nile—to assassinate the new heir, Turanshah.

For a brief, remarkable period, Shajar al-Durr ruled as Sultana. To solidify her position in a male-dominated world, she married a Mamluk commander, Aybak. He soon sidelined her and declared himself sultan, officially inaugurating the Mamluk Sultanate. The slaves had become the masters.

Halting the Unstoppable: The Mamluks vs. the Mongols

The newly formed Mamluk state was immediately faced with an existential threat that had crushed every other power in its path: the Mongol Empire. In 1258, the Mongol hordes under Hulagu Khan had sacked Baghdad, the intellectual and spiritual heart of the Islamic world, and executed the last Abbasid Caliph. The wave of terror and destruction was sweeping west towards Syria and Egypt.

Cairo was in a panic. But the Mamluk Sultan Qutuz, aided by his brilliant and ruthless general, Baybars, decided to confront the threat head-on. In 1260, the Mamluk and Mongol armies met in Palestine at a place called Ain Jalut (“the Spring of Goliath”). Using clever feigned-retreat tactics, the Mamluks lured the Mongol cavalry into an ambush and annihilated them. It was the first time a major Mongol army had been decisively defeated in open battle.

The victory at Ain Jalut was a world-changing event. It shattered the myth of Mongol invincibility and saved Egypt, the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, and likely North Africa from conquest. The Mamluks became the undisputed champions and defenders of the Islamic faith, a role they relished and used to legitimize their rule.

The Golden Age of Mamluk Cairo

With the destruction of Baghdad, Cairo became the preeminent city of the Islamic world. Refugees, scholars, and artisans flocked to the Mamluk capital, sparking a cultural and artistic golden age. The Mamluk sultans, flush with wealth from their control over the lucrative spice trade between the East and Europe, became extravagant patrons of art and architecture.

They transformed the skyline of Cairo, constructing massive, multi-functional complexes that often included a mosque, a madrasa (school), a mausoleum for the patron, and a hospital. Mamluk architecture is characterized by its monumental scale, intricate stone carving, soaring domes, and elegant minarets. Masterpieces from this era still dominate Cairo today, including:

- The Sultan Hassan Mosque-Madrasa: An immense and awe-inspiring structure, considered one of the finest examples of early Mamluk architecture.

- The Qalawun Complex: A sprawling foundation that included a renowned hospital (maristan) that provided free medical care to all for centuries.

- The Khan el-Khalili: This famous bazaar, while having older roots, was largely rebuilt and organized under the Mamluks, becoming the economic heart of the city.

Beyond architecture, Mamluk artisans excelled in producing exquisite decorative arts. Intricately inlaid metalwork, gilded and enameled mosque lamps, and luxurious illuminated Qurans are all hallmarks of this period. The Mamluks didn’t just rule; they adorned their world with a spectacular and lasting beauty.

A System in Decline: The End of an Era

For all its strengths, the Mamluk system contained the seeds of its own destruction. Their rule is typically divided into two periods: the Bahri (1250–1382) of Turkic origin and the Burji (1382–1517) of Circassian origin. The key weakness was succession.

Power was not hereditary; it was taken by the most powerful Mamluk emir. While this ensured strong leaders in the early days, it devolved into a cycle of bloody coups, assassinations, and civil wars. The sultan’s reign was often short and violent. This internal instability was compounded by external disasters. The Black Death in the mid-14th century wiped out a huge portion of the population, crippling the economy and the military. Later, in 1498, the Portuguese discovery of a direct sea route to India around Africa allowed them to bypass the Mamluk-controlled trade routes, devastating the sultanate’s main source of income.

The final blow came from a new, formidable power: the Ottoman Empire. Armed with modern cannons and firearms, the Ottoman army of Sultan Selim I was more than a match for the Mamluk cavalry, which still relied on the traditional tactics of bow and lance. In 1517, at the Battle of Ridaniya outside Cairo, the Ottomans crushed the Mamluk forces. The last Mamluk sultan, Tuman Bay II, was captured and ignominiously hanged at a Cairo city gate. Egypt became a province of the Ottoman Empire, and the sun set on the Mamluk Sultanate.

Though their state was conquered, the Mamluks’ legacy endures. They were a military paradox who rose from bondage to build an empire, protect their faith from an unstoppable force, and sponsor an artistic flourishing that forever defined the face of Cairo. Their story is a powerful testament to the turbulent, complex, and brilliant history of the medieval world.