Imagine you stand accused of a crime in 10th-century Europe. There are no witnesses, no physical evidence, no confession. In a world without forensic science or established detective work, how can a court possibly determine your guilt or innocence? For the people of the early and high Middle Ages, the answer was simple yet profound: they would ask God directly.

This was the world of the iudicium Dei, or the “judgment of God”—what we know today as trial by ordeal. Far from being a barbaric free-for-all, the ordeal was a deeply serious judicial and religious ceremony. It was founded on the unshakable belief that God, being all-knowing and perfectly just, would actively intervene in human affairs to reveal the truth and protect the innocent. To a modern observer, it looks like a deadly game of chance. To the medieval mind, it was a sacred appeal to the highest court in the universe.

A World Steeped in Divine Justice

To understand the logic of the ordeal, we must first step into the medieval worldview. This was not a society that saw God as a distant, deistic clockmaker who wound up the universe and let it run. God was an omnipresent and active force in every aspect of life, from the changing of the seasons to the outcome of a battle. Miracles were not just stories from the Bible; they were considered real, possible, and even expected events.

When a secular court reached an impasse due to a lack of evidence, it was logical for them to turn the case over to this higher, divine authority. The trial by ordeal was the formal mechanism for doing so. The process was heavily ritualized and overseen by the clergy, lending it immense solemnity. The accused would often be required to fast, pray, and attend Mass for several days leading up to the ordeal. The tools of the ordeal—the water, the iron, the fire—were blessed by a priest, transforming them from ordinary elements into instruments of God’s will. This wasn’t merely a legal procedure; it was a sacrament, a moment where the sacred and the secular collided to produce justice.

The Ordeals in Practice: Fire, Water, and Combat

While variations existed across Europe, three main forms of ordeal became common practice. Each was designed to provide a clear, binary sign of God’s judgment.

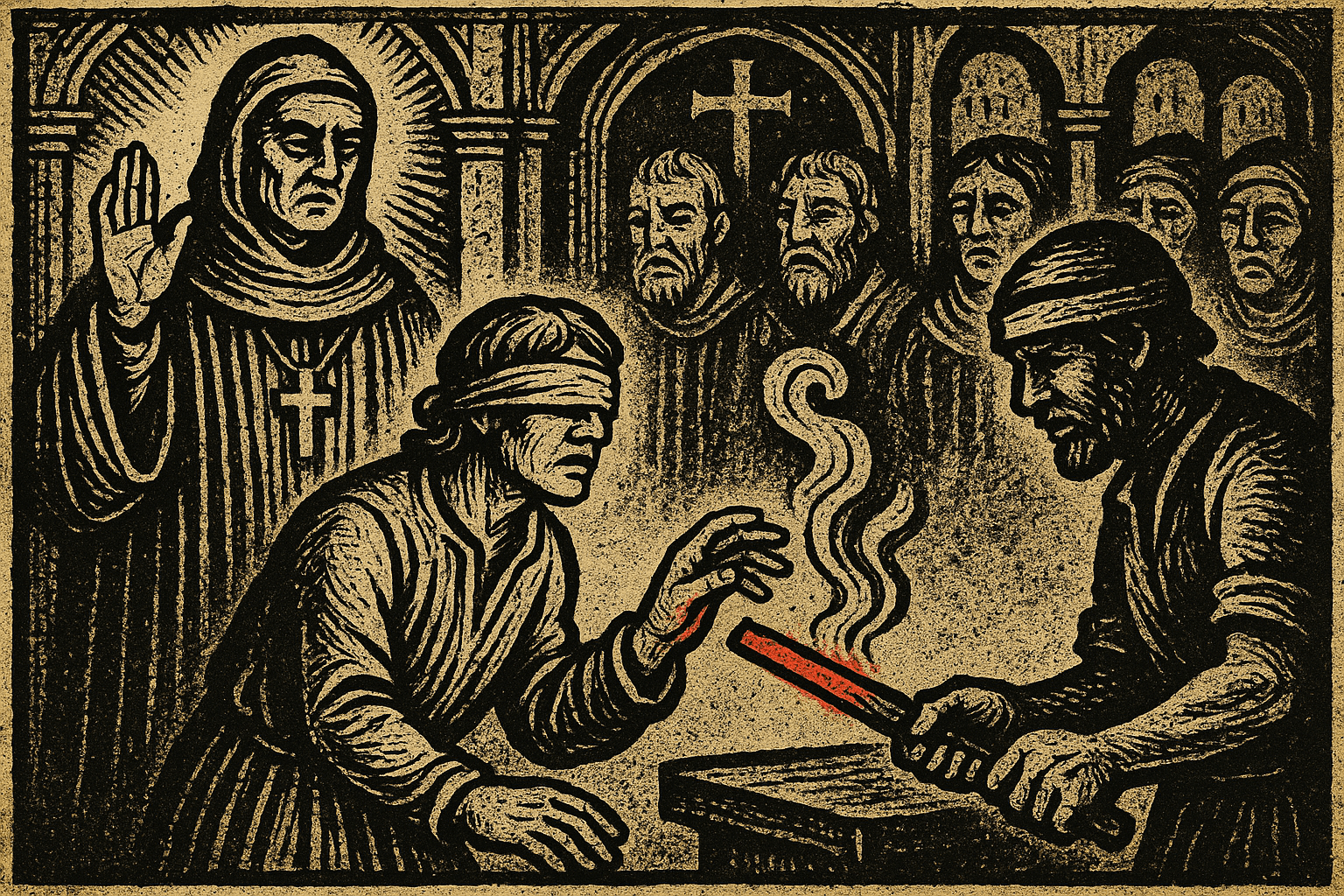

Ordeal by Fire (Ordalium Ignis)

One of the most common ordeals involved fire. In one version, the accused was required to carry a piece of red-hot iron, weighing between one and three pounds, for a set number of paces. In another, they would walk barefoot across nine heated plowshares. Immediately afterward, the burned hand or foot was bandaged and sealed by the priest. Three days later, the bandages were removed in a public ceremony. If the wound was healing cleanly, without infection, God had performed a miracle to prove their innocence. If the wound was festering and infected, it was a clear sign of their guilt and divine condemnation.

Ordeal by Cold Water (Ordalium Aquae Frigidae)

The ordeal by water is perhaps the most counterintuitive to modern sensibilities. The accused was bound—often thumb to opposite toe—and lowered by a rope into a body of cold water that had been ritually blessed. Here’s the crucial part: floating was a sign of guilt. The logic was that the pure, sanctified water would actively “reject” the sinful, guilty person. Sinking, by contrast, was a sign of innocence, as the pure element “accepted” the accused. The person was, of course, tied to a rope and was to be pulled out quickly if they sank, so sinking was not intended to be a death sentence in itself. It was the sign from God that mattered.

Ordeal by Combat (Duellum)

Most popular among the nobility, the trial by combat pitted the accuser and the accused (or their chosen champions) against each other in a fight. The logic was straightforward: “God will grant victory to the righteous.” This was a deadly serious duel, often ending in death or severe injury. It reflected the martial values of the warrior class, combining physical prowess with divine favor. Importantly, this ordeal recognized social realities; women, children, the clergy, or the elderly could be represented by a champion—a physically able warrior who would fight on their behalf.

More Than a Game of Chance: The Social and Psychological Logic

While the theological framework is clear, the ordeal system also functioned on a powerful social and psychological level. It wasn’t quite the 50/50 gamble it appears to be.

- A Tool for Confession: The sheer terror of the ordeal was a potent tool for eliciting confessions. The multi-day ritual of fasting, prayer, and public scrutiny, all culminating in a physically agonizing test, would weigh heavily on a guilty person’s conscience. Many chose to confess rather than face what they believed would be certain exposure and damnation by God Himself.

- Reinforcing Community Consensus: An ordeal was typically a last resort, ordered by a court or community that was already suspicious. The process and its outcome often served to publicly ratify a conclusion the community had already reached. It provided a definitive, divinely-sanctioned end to a dispute, restoring social harmony.

- The Priest’s Discretion: The system was not as objective as it sounds. In the ordeal by fire, the priest was the one to unwrap the wound and declare whether it was “healing cleanly.” This offered a significant degree of human intervention. If the accused was a respected member of the community and widely believed to be innocent, the priest might be more inclined to interpret an ambiguous wound favorably. This allowed a degree of “managed justice” to be folded into the divine judgment.

The End of the Ordeal

The slow decline of the trial by ordeal began not with a sudden wave of rationalism, but with a shift in theology. By the early 13th century, leading thinkers within the Church began to question the practice. They argued that the ordeal was not a humble appeal to God, but a prideful act of “tempting” God—of demanding a miracle on a human schedule. The Bible itself warned, “You shall not put the Lord your God to the test.”

The decisive blow came in 1215 at the Fourth Lateran Council. Pope Innocent III, one of the most powerful popes in history, formally forbade clergy from participating in or lending religious legitimacy to any trial by ordeal. Without the priests, the blessings, and the Mass, the ordeal lost its entire theological foundation. It devolved from a sacred iudicium Dei into mere torture.

Deprived of their divine method for truth-finding, secular courts were forced to innovate. This prohibition created a judicial vacuum that spurred the development of the legal systems we recognize today. In England, it encouraged the growth of the jury system, where a body of local men would weigh evidence. On the continent, it led to the rise of the inquisitorial system, which relied on judicial investigation. The end of the ordeal didn’t just close a chapter on medieval justice; it opened the book on the modern legal world.