The Chosen Few: Becoming a Vestal

A Vestal Virgin did not choose her path; it was chosen for her. Between the ages of six and ten, a young Roman girl could be selected for this most sacred of offices. The selection was made by the Pontifex Maximus, Rome’s chief high priest. The criteria were stringent: she had to be a free-born daughter of a patrician family, with both parents still living, and be free of any physical or mental imperfections. She was, in essence, a perfect offering to the goddess.

The initiation was a profound separation from her old life. The young girl was brought before the Pontifex Maximus, who would take her by the hand and utter the formal words, “I take you, Amata, to be a Vestal priestess…” Her hair was ceremonially cut and hung on a sacred tree, symbolizing the sacrifice of her former identity. She was stripped of her family name and called simply Amata (“Beloved”). Dressed in the white robes of her new office, she entered the House of the Vestals (Atrium Vestae) in the Roman Forum, a home she would not leave for three decades.

Her term of service was rigidly structured over thirty years:

- Ten years as a novice: Learning the complex rites, rituals, and sacred duties from her senior sisters.

- Ten years as a priestess: Performing the core duties of the office at the height of her service.

- Ten years as a teacher: Instructing the next generation of novices.

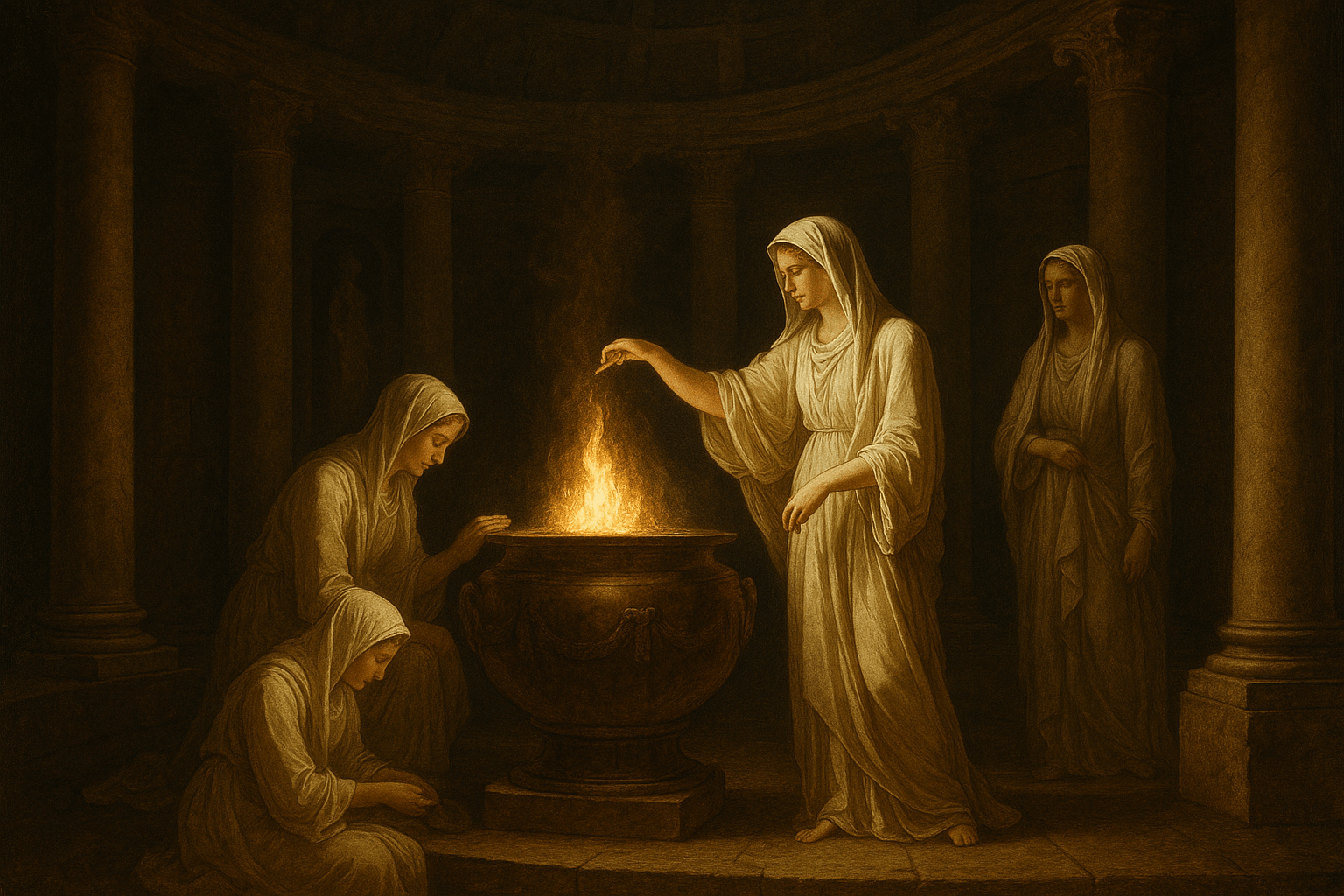

Guardians of the Eternal Flame

The central and most vital duty of a Vestal Virgin was to tend the sacred fire in the Temple of Vesta. This was no ordinary flame. It was believed to be intrinsically linked to the life and fortune of Rome itself. Vesta was the goddess of the hearth, home, and family—the very foundation of Roman civilization. As long as her fire burned, Rome would endure. If it went out, it was considered a terrifying omen, a sign that the goddess had withdrawn her protection and the city was doomed.

The Vestal on duty who allowed the flame to be extinguished was considered gravely negligent and was scourged by the Pontifex Maximus in a dark room. The fire would then have to be relit through a primitive method, by rubbing two sticks together, as using an existing flame was forbidden.

Beyond the fire, their duties included:

- Preparing the mola salsa, a ritual mixture of coarse-ground, salted flour used in nearly all official state sacrifices.

- Fetching water from the sacred spring of the nymph Egeria, which had to be carried in a vessel called a futile that could not be set down without spilling, symbolizing constant vigilance.

- Guarding sacred objects stored within the temple, including the legendary Palladium—a statue of Pallas Athena said to have been rescued from Troy, whose presence was thought to guarantee Rome’s invincibility.

A Life of Unprecedented Privilege

While their personal lives were severely restricted, the public status of a Vestal Virgin was immense. In a society where women lived under the legal authority of a male guardian—first their father (paterfamilias) and then their husband—the Vestals were a stunning exception. Upon taking their vows, they were immediately freed from their father’s control (patria potestas). They could own property, make contracts, write a will, and even testify in court without a male representative. These were rights unheard of for almost any other woman in Rome.

Their prestige extended into public life. They had reserved seats of honor at the front of the Colosseum and other public spectacles. When they traveled through the city in their covered carriage (carpentum), they were preceded by a lictor, a type of bodyguard who would clear the way for them—a right otherwise reserved for high-ranking magistrates. To harm a Vestal, or even to pass beneath her litter, was a capital offense. In a remarkable display of their sacred authority, if a Vestal happened upon a criminal being led to execution, the condemned person was automatically pardoned.

The Ultimate Price: Buried Alive

All these privileges hinged on one absolute, unbreakable vow: chastity. For thirty years, from childhood until middle age, a Vestal Virgin had to remain pure. Her virginity was not just a personal matter; it was a state concern of the highest order. Her physical purity was a mirror for the spiritual purity and integrity of Rome. If she broke this vow (crimen incesti), it was considered a profound religious pollution that endangered the entire state.

The punishment was one of the most horrifying spectacles in the Roman world. Because a Vestal’s body was consecrated, her blood could not be shed. So, the Romans devised a chilling solution to execute her without technically killing her. The guilty Vestal was dressed in grave clothes and carried in a closed, silent litter—like a corpse—through a grieving city. The procession ended at a place called the Campus Sceleratus, or “The Evil Field.”

There, an underground chamber had been prepared, containing a small bed, a lighted lamp, and a meager portion of bread, water, milk, and oil. The Pontifex Maximus would say a prayer, and the condemned woman would descend a ladder into her tomb. The ladder was removed, the entrance sealed, and the earth piled back on top. She was left to die of suffocation or starvation, abandoned by the gods she was supposed to serve. The state, having provided her with sustenance, could claim it had not killed her but merely left her to a fate decided by the divine. Her male partner in the crime suffered a more straightforward, brutal end: he was publicly flogged to death in the Forum.

A Life After Service

If a Vestal successfully completed her thirty years of service, she was free. At around the age of forty, she could leave the priesthood, receive a generous state pension, and was permitted to marry. For a woman who had known unparalleled autonomy and public reverence, however, this was a mixed blessing. Many chose to remain within the college of priestesses, living out their days as respected elders. To marry and subordinate themselves to a husband after decades of independence and immense public honor was, for many, a step down.

The Vestal Virgins were a paradox at the heart of Rome. They were simultaneously servants and symbols, revered and confined. Their lives were a testament to the Roman belief in ritual, discipline, and the profound connection between personal purity and the fate of an empire. They were powerful women in a man’s world, but their power came at a cost that few could—or would be willing to—endure.