Legalism was not a philosophy for the common person; it was a cold, calculating handbook for rulers. It emerged during the turbulent Warring States period (c. 475-221 BCE), a time of incessant warfare and political chaos. Thinkers across China desperately sought a way to end the bloodshed and create a strong, stable state. While Confucians looked to the moral virtue of past sage-kings, the Legalists scoffed. They saw human nature as inherently selfish and lazy. Appealing to morality, they argued, was like trying to stop a flood with a handful of sand. The only thing people understood was self-interest, driven by a clear system of rewards and punishments.

The Three Pillars of Power

Legalist philosophy was not a monolithic doctrine but an amalgamation of ideas that were later synthesized, most famously by the philosopher Han Fei. These ideas can be distilled into three core concepts that formed the pillars of the Legalist state.

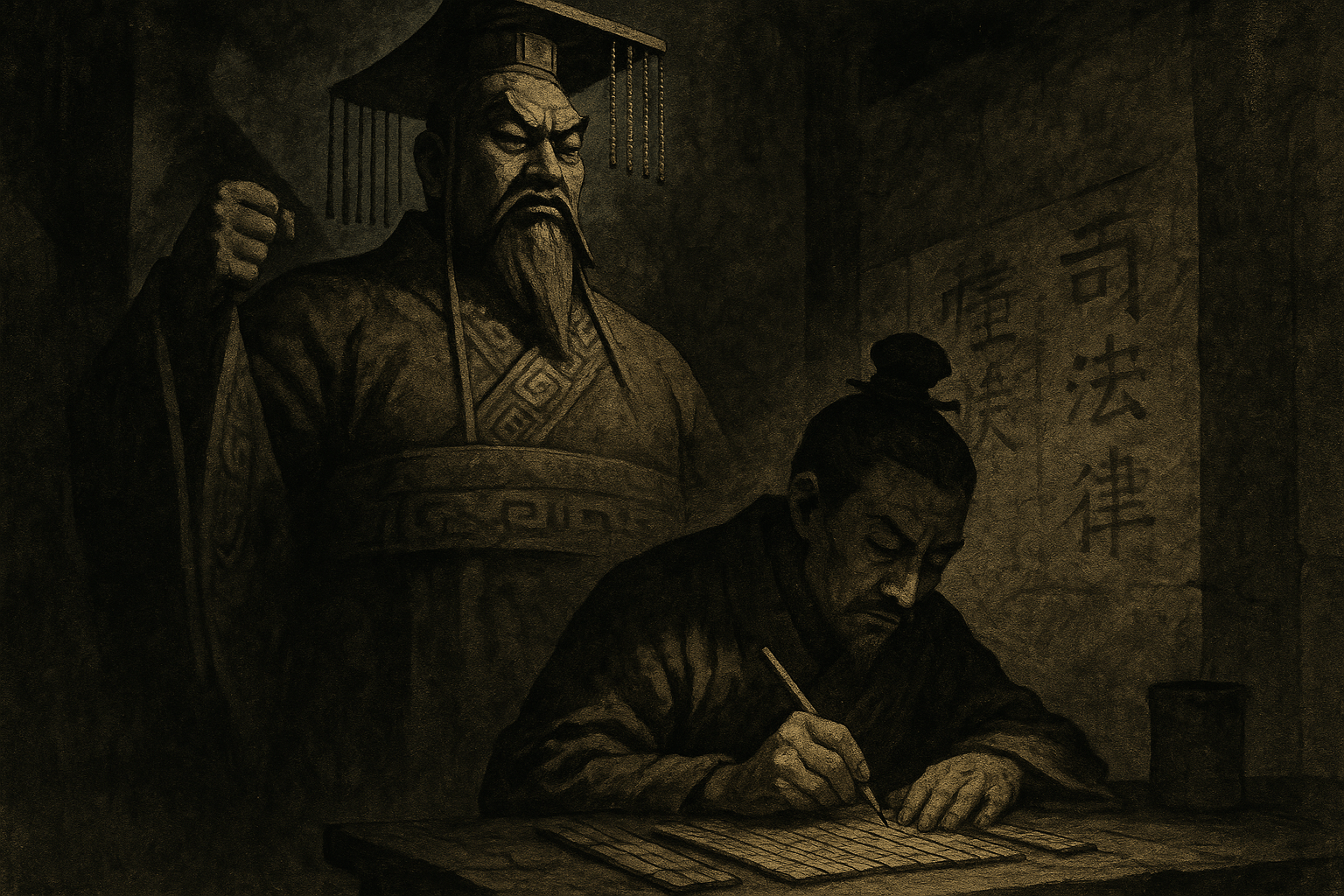

1. Fa (法): The Supremacy of Law

For Legalists, the law was everything. But this wasn’t law based on tradition or divine will; it was a set of clear, public, and objective rules decreed by the ruler. Fa had to be simple enough for anyone to understand and, most importantly, it had to be applied to everyone equally, from the highest minister to the humblest peasant. No one was above the law. This was a radical departure from the aristocratic, feudal system where birthright determined one’s status and treatment. The law was the ultimate tool for standardizing behavior and creating social order.

2. Shu (術): The Secret Art of Statecraft

While the laws were public, the ruler’s methods for maintaining power were to be kept secret. Shu refers to the tactics, or “arts of the ruler”, used to control the bureaucracy. A Legalist ruler should be enigmatic and inscrutable, never revealing his true intentions or desires. This kept ministers guessing and prevented them from manipulating him for their own gain. The ruler’s job was to “hold the handles” of power, evaluating his officials solely on whether their performance (xing) matched the duties of their proposed title (ming). If performance exceeded the job description, it was as bad as failing to meet it, as it suggested the official was overstepping his bounds.

3. Shi (勢): The Inherent Power of Position

Legalists were realists. They knew not every ruler would be a sage. Shi solves this problem by arguing that power and authority come from the position (the throne), not from the personal qualities of the individual occupying it. An average ruler in a position of immense power is far more effective than a brilliant scholar with no authority. The system, therefore, was designed to function regardless of the ruler’s personal virtue or wisdom. The throne itself held the legitimacy, and the ruler’s job was to wield the power inherent in that position without hesitation.

“Two Handles”: Carrots and Brutal Sticks

At the heart of Legalist practice was a simple but terrifyingly effective system of social control known as the “Two Handles”: reward and punishment.

- Rewards (The Carrot): The state encouraged exactly two professions: farming and soldiering. High agricultural yields or exceptional bravery in battle were lavishly rewarded with wealth, rank, and social standing. This laser-focus was designed to strengthen the state’s economic and military foundations.

- Punishments (The Stick): This was the handle the Legalists used most forcefully. Punishments were deliberately severe and merciless to deter any deviation from the law. Minor offenses could lead to hard labor on projects like the Great Wall. More serious crimes resulted in horrific mutilations (such as tattooing the face or amputation of the nose or feet) or execution, often involving the entire family or community to enforce collective responsibility.

The goal was to create a society where the fear of punishment was so great that people wouldn’t even consider breaking the law.

The Architects of an Empire: Shang Yang and Li Si

Legalism was not just theory; it was put into devastating practice. Its first major trial was in the state of Qin under the minister Shang Yang in the 4th century BCE. Shang Yang ruthlessly reformed Qin, abolishing feudal land ownership, creating a direct tax system, and enforcing his harsh legal code. He organized the population into groups of five and ten households, making them mutually responsible for each other’s crimes. His reforms transformed Qin from a backwater state into a military juggernaut. In a classic twist of Legalist irony, when his patron ruler died, Shang Yang was accused of treason and was killed by being pulled apart by five chariots—a victim of the very system he created.

Centuries later, the statesman Li Si, a student of the leading Legalist philosopher Han Fei, became the chancellor to Qin Shi Huang, the man who would conquer all other states and declare himself the First Emperor of China in 221 BCE. Under Li Si’s guidance, the entire newly-unified China was reorganized along Legalist principles. He oversaw the standardization of currency, weights, measures, road widths, and—most famously—the written script. To eliminate intellectual dissent, Li Si instigated the infamous “burning of the books and burying of the scholars”, an event that saw the destruction of countless philosophical and historical texts deemed subversive to Qin authority.

The Double-Edged Legacy

The Qin Dynasty was brutally effective. It ended centuries of war, created the political and administrative structure that would define China for two millennia, and completed massive infrastructure projects like the early Great Wall. The Terracotta Army itself stands as a testament to its incredible organizational power.

However, this efficiency came at an unbearable human cost. The Qin’s reliance on terror and slave labor fostered immense resentment. Just a few years after Qin Shi Huang’s death in 210 BCE, widespread rebellions erupted, and the dynasty that was meant to last for “ten thousand generations” collapsed in a mere 15 years.

The succeeding Han Dynasty publicly repudiated Legalism in favor of Confucianism. But this was a clever political move. In reality, they created a synthesis that has defined Chinese governance ever since: “Confucian on the outside, Legalist on the inside” (儒表法里, rú biǎo fǎ lǐ). While the state promoted Confucian ethics of benevolence and propriety, its administrative core—the bureaucracy, the use of law to control the populace, and the focus on a strong, centralized state—retained the unmistakable stamp of hard-nosed Legalist pragmatism.

Legalism remains a stark and unsettling chapter in world history. It serves as a powerful reminder that order and unity can be forged through fear and control, but that such a regime, devoid of humanism and compassion, rests on a brittle and ultimately unsustainable foundation.