Who Were the Lapita People?

The term “Lapita” doesn’t refer to a single political state or empire, but rather to a widespread cultural complex that flourished in the Pacific between roughly 1500 and 500 BCE. Archaeologists identify them primarily through a shared, highly distinctive artifact: their pottery. Lapita pottery is famous for its intricate geometric patterns, meticulously applied to the clay using a small, comb-like tool in a technique called “dentate-stamping.” These patterns, featuring repeating motifs, lines, and sometimes stylized faces, are a unique cultural fingerprint found across thousands of miles of ocean.

Originating from the Austronesian expansion out of Southeast Asia (likely Taiwan), the Lapita people arrived in the Bismarck Archipelago, just east of New Guinea, already equipped with a sophisticated toolkit for survival and colonization. They carried with them a “portable homeland”—a suite of domesticated plants and animals that included taro, yams, bananas, coconuts, pigs, chickens, and dogs. They were skilled artisans, creating beautiful shell jewelry and using obsidian (a volcanic glass) to craft razor-sharp tools.

The Great Leap into the Void

For millennia, human settlement in the Pacific was confined to what we now call “Near Oceania”—New Guinea, Australia, and the Solomon Islands. These were large landmasses that were, for the most part, inter-visible. You could stand on the shore of one island and see the next. But beyond the Solomons lay “Remote Oceania”, a vast and empty seascape dotted with tiny, isolated islands invisible from any other shore.

Around 1200 BCE, the Lapita did something no human had ever done before: they pushed off from the shores of the Solomon Islands and sailed east into the unknown. This wasn’t a slow, tentative process. In a breathtakingly rapid expansion lasting just a few centuries, they settled a chain of islands stretching over 4,500 kilometers, from Vanuatu and New Caledonia, through Fiji, and all the way to Tonga and Samoa. They were the first people ever to set foot on these pristine islands.

The Vessels of Exploration: The Outrigger Canoe

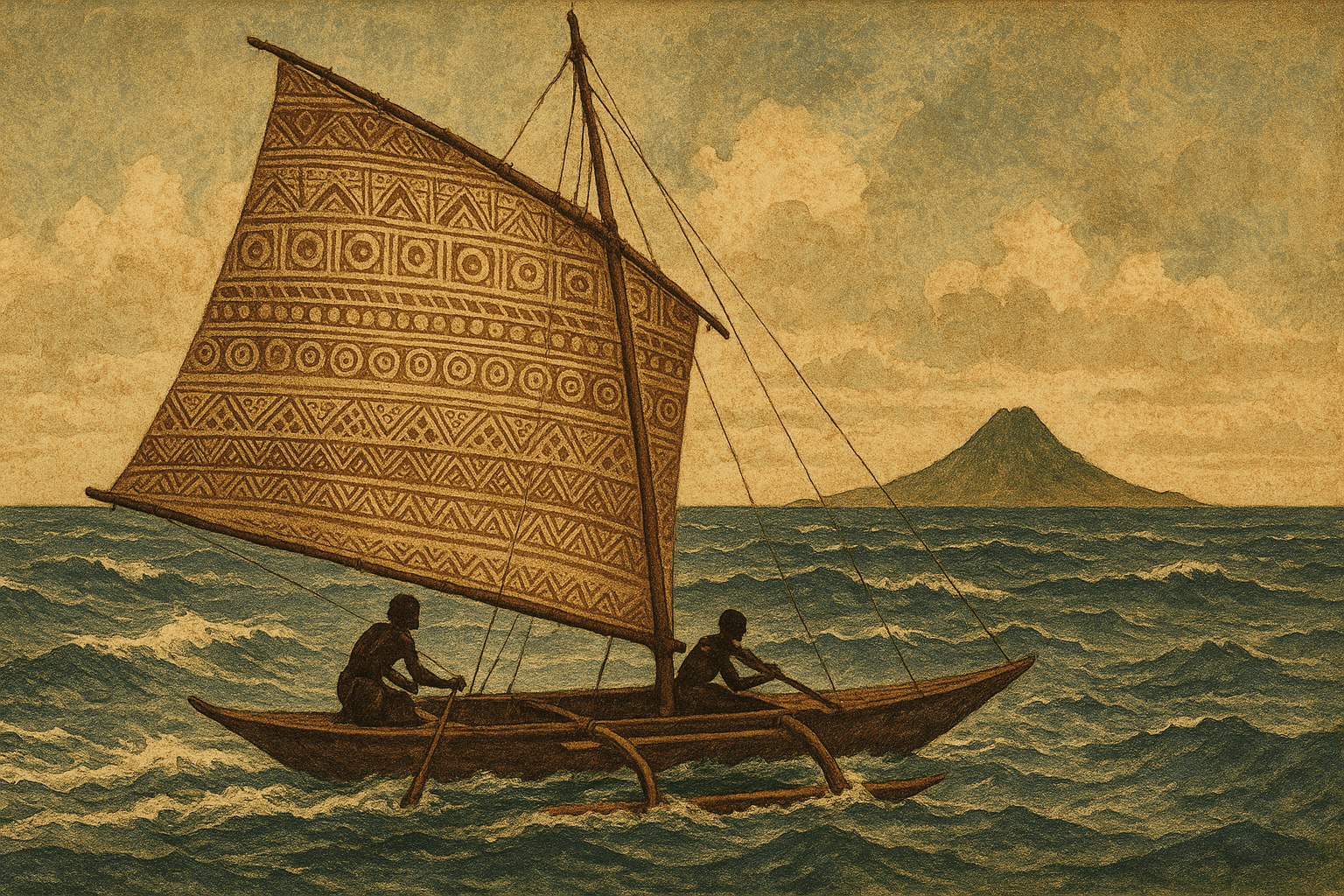

This incredible feat was only possible because the Lapita had perfected a revolutionary piece of technology: the ocean-going outrigger canoe. These were not simple dugout logs. They were large, sophisticated sailing vessels, likely built as double-hulled catamarans or with a single outrigger float for stability. This design made them stable in rough seas, fast, and capable of being sailed into the wind.

Most importantly, they could carry significant cargo. A single voyage would have transported dozens of people, their precious planting materials, breeding pairs of animals, tools, and enough water and food for weeks at sea. These canoes were not just boats; they were mobile ecosystems, floating platforms of colonization that allowed the Lapita to transplant their entire way of life across the ocean.

Masters of the Sea: A Mental Map of the Ocean

How did the Lapita navigate without instruments? They used a complex and brilliant system of non-instrumental wayfinding, a body of knowledge passed down through generations. This was a mental map of the ocean, read through environmental signs.

- The Star Compass: Navigators memorized the rising and setting points of dozens of stars and constellations. By keeping their canoe aligned with a specific star on the horizon, they could maintain a precise directional course.

- Sun and Moon: The path of the sun during the day and the moon at night provided crucial directional cues.

- Ocean Swells: Perhaps the most sophisticated technique was reading the patterns of ocean swells. Long-distance swells travel in a consistent direction for thousands of miles. A trained navigator could feel this pattern in the movement of the canoe, allowing them to hold their course even under cloudy skies. They also understood how swells refract and bend around islands, creating distinct patterns that signaled land was near, long before it was visible.

- Natural Signs: In the final stages of a voyage, navigators relied on other clues. They watched for land-based birds, which fly out to sea in the morning to feed and return to their island home in the evening. They looked for specific cloud formations that tend to build up over islands or the greenish reflection of a shallow lagoon on the underside of clouds.

A Portable Homeland on a New Shore

Upon discovering a new, uninhabited island, the Lapita would set about transforming it into a home. They sought out coastal plains and lagoons, ideal locations for their villages. There, they would plant the taro, yams, and breadfruit they had carefully transported across the sea. They released their pigs and chickens, establishing the agricultural basis for a new, self-sufficient community.

Their arrival had a profound and permanent impact. They were the first large mammals on many of these islands, and their activities, combined with the animals they introduced, led to significant ecological changes, including the extinction of many species of native birds. In clearing land for gardens and building their settlements, they began actively shaping the landscapes of Oceania, a process their descendants would continue for centuries.

The Lapita Legacy: Foundations of Polynesia

By around 500 BCE, the distinctive Lapita pottery style began to fade from the archaeological record, and the rapid, long-distance expansion paused for nearly a thousand years in the heart of Polynesia (Tonga and Samoa). But the Lapita people did not disappear. Their culture evolved, their populations grew, and their navigational knowledge was refined.

They laid the cultural, linguistic, and technological foundation for what would become the great Polynesian societies. It was from this Samoan-Tongan homeland that, centuries later, their descendants would launch the final, even more ambitious, wave of exploration. They would use the same fundamental canoe technology and wayfinding principles, honed by the Lapita, to settle the vast “Polynesian Triangle”—a remote and far-flung world from Hawaiʻi in the north, to Rapa Nui (Easter Island) in the southeast, and Aotearoa (New Zealand) in the southwest.

The story of the Lapita is a testament to human curiosity and endurance. They were not just migrants; they were the architects of a new human world, turning a water world into a network of island homes. Their epic voyages, guided by starlight and ancestral knowledge, stand as one of the greatest achievements in the history of exploration.