Thriving from approximately 100 to 940 CE in the highlands of modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea, Aksum was no isolated kingdom. It was a cosmopolitan powerhouse, a crucial link in the chain of global commerce, and a beacon of cultural and religious innovation. Its story is one of immense wealth, staggering engineering, and a revolutionary embrace of faith that would shape the region for millennia to come.

A Crossroads of Continents: The Engine of Aksumite Wealth

Location is everything, and Aksum’s position was strategically brilliant. Nestled along the Red Sea coast, it controlled a vital maritime choke-point. The kingdom’s main port, Adulis, was a bustling, multicultural hub where merchants from across the known world converged. It was here that the Roman Mediterranean met the exotic markets of India and beyond.

A 1st-century CE guide for Greco-Roman merchants, the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, describes Adulis in detail, listing the incredible variety of goods that flowed through Aksum. The kingdom exported precious resources highly sought after in the Roman Empire, such as:

- Ivory

- Rhinoceros horns

- Tortoise shells

- Gold

- Emeralds

- Obsidian

In return, Aksumite markets were filled with foreign luxuries: dyed cloth and cloaks from Egypt, glassware, olive oil and wine from the Roman Empire, and spices, iron, and steel from India. This lucrative trade didn’t just make the kingdom rich; it made it a respected international player. To manage this complex economy, the Aksumite kings took a groundbreaking step: they began minting their own currency around the late 3rd century CE. Aksum was one of the first African civilizations to do so, placing it in an elite club alongside Rome, Persia, and Kush. These coins, stamped in gold, silver, and bronze—often with inscriptions in Greek and the local Ge’ez script—were a clear declaration of Aksum’s sovereignty and economic might.

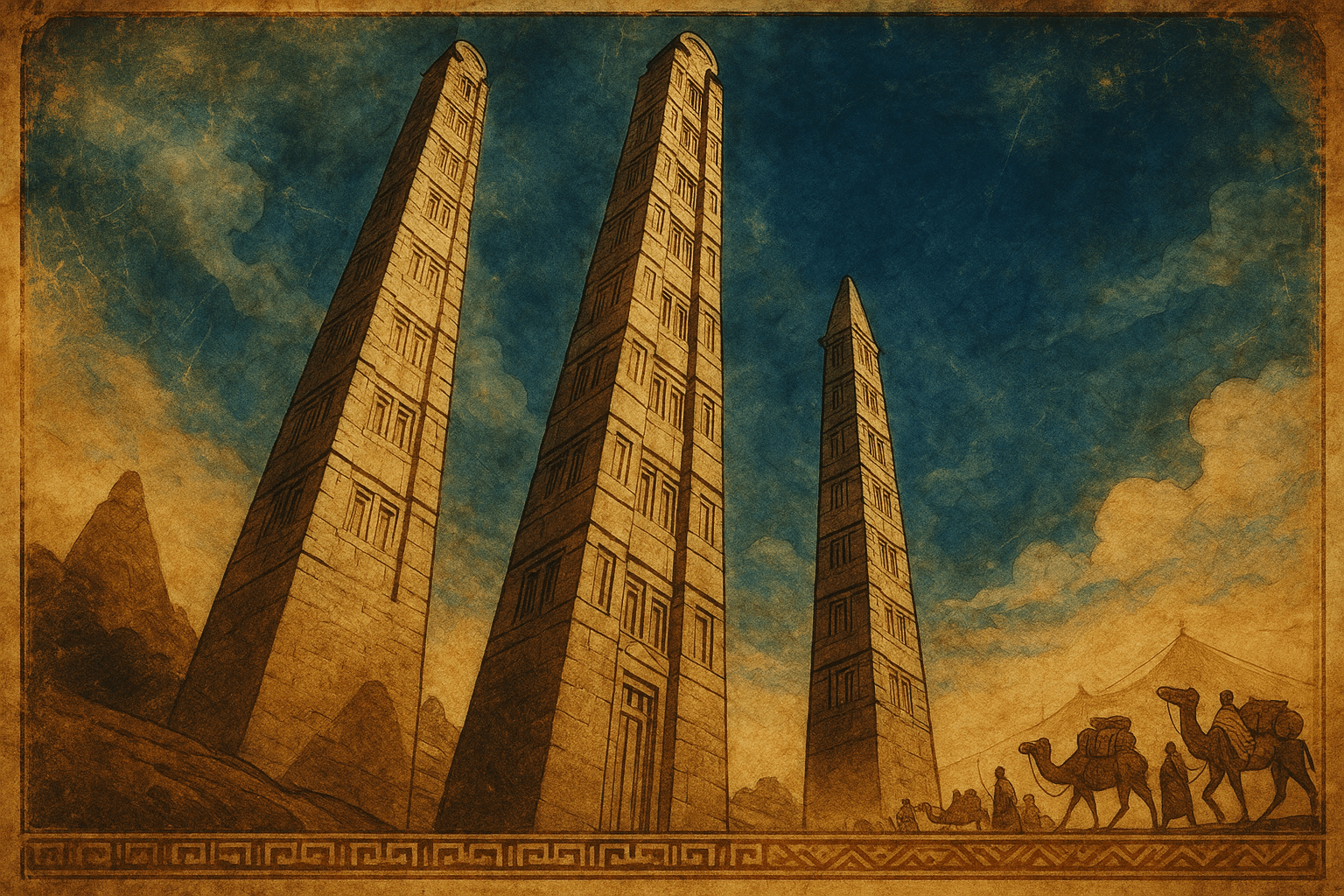

Skyscrapers of the Ancient World: The Great Stelae of Aksum

As you walk through the ancient capital, also named Aksum, a forest of stone towers rises from the earth. These are the stelae—single, massive granite obelisks erected as grave markers for the kingdom’s rulers and nobility. They are not just monuments; they are breathtaking feats of engineering and artistry that silently proclaim the power of the kings buried beneath them.

Carved to resemble multi-story buildings, complete with false doors at the base and intricate window carvings climbing to the top, these stelae symbolized a permanent palace for the deceased in the afterlife. The largest and most famous is the Great Stele. If it were still standing, it would soar 33 meters (108 feet) high, weighing an estimated 520 tons. It is the largest single piece of stone ever quarried and erected by humans in the ancient world. Tragically, this behemoth likely fell and shattered during its erection, its massive fragments still lying where they fell centuries ago.

Another iconic monument, the Obelisk of Aksum, stood 24 meters tall before it was looted by Mussolini’s troops in 1937 and taken to Rome. For decades, it stood as a controversial symbol in the Piazza di Porta Capena. After a long diplomatic process, Italy finally returned the stele to Ethiopia in 2005, where it was re-erected in 2008—a powerful moment of cultural repatriation and a testament to the enduring significance of these ancient wonders.

A Kingdom For Christ: Aksum’s Conversion

While its economic and architectural achievements were profound, Aksum’s most lasting legacy may be its early and trailblazing adoption of Christianity. Before the 4th century CE, Aksumite religion was polytheistic, worshipping gods like Astar, the god of the sky, and Mahrem, a deity of war. This is evident on early coins, which feature a disk and crescent symbol.

Everything changed under the reign of King Ezana in the mid-4th century. The story, told by the historian Rufinus, is captivating. A Syrian Christian philosopher named Meropius was traveling by sea with two young relatives, Frumentius and Aedesius. Their ship was attacked near the coast of Aksum, and everyone aboard was killed except for the two boys. They were taken to the king’s court, where their education and intelligence impressed the monarch. Frumentius eventually became a trusted advisor and tutor to the young prince, Ezana.

When Ezana ascended to the throne around 330 CE, Frumentius had sown the seeds of the Christian faith in him. King Ezana declared Christianity the official state religion, making Aksum one of the very first kingdoms in the world to do so—decades before the Roman Empire would make a similar declaration. This pivotal moment is documented in stone and metal. King Ezana’s later inscriptions are dedicated to the “Lord of Heaven”, and his coins replace the old pagan symbols with the Christian cross. This conversion forged a powerful alliance with the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire and set the cultural and religious trajectory for what would become modern Ethiopia.

The Fading of a Superpower

Like all great empires, Aksum’s golden age eventually came to an end. Its decline began in the 7th century, driven by a combination of factors. The rise of Islamic caliphates in Arabia reoriented global trade, shifting power away from the Red Sea and isolating Aksum from its Christian allies in Byzantium. The port of Adulis was eventually destroyed, severing the kingdom’s main artery of wealth.

At the same time, environmental challenges, likely including deforestation and climate change, may have degraded the land and reduced agricultural yields. The center of Aksumite power gradually shifted south into the more fertile Ethiopian highlands, and the kingdom slowly fragmented.

Yet, the legacy of Aksum never truly vanished. It lives on in the powerful Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, in the ancient Ge’ez script that is still used in liturgical services, and in the profound sense of history that defines the Ethiopian and Eritrean people. Aksum was not just a regional power; it was a cornerstone of the ancient world, a true African superpower whose echoes resonate to this day.