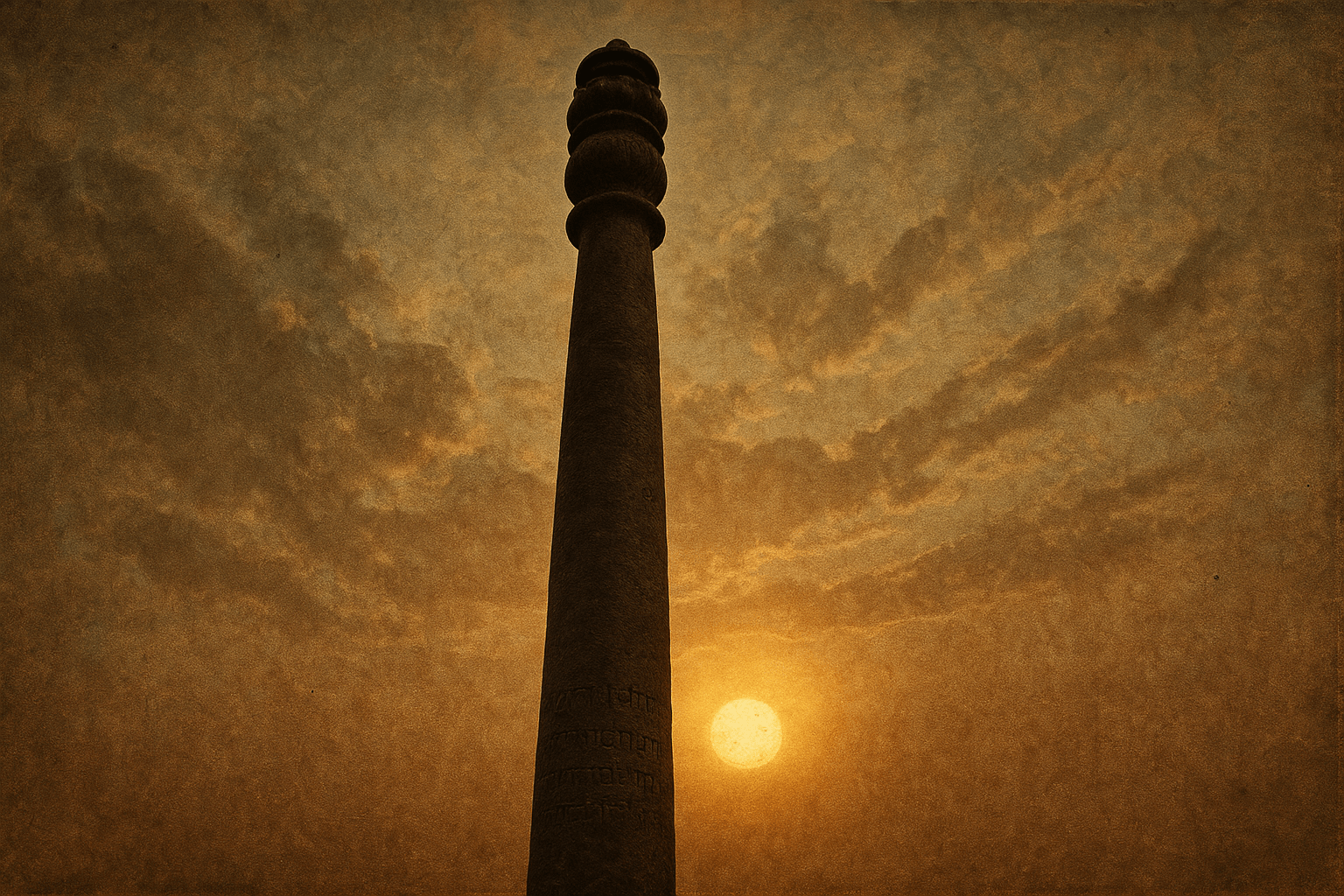

A Pillar with a Past

To understand the pillar’s mystery, we must first travel back to the golden age of ancient India: the Gupta Empire. The pillar’s story begins not in Delhi, but in a location that is still debated by historians. An inscription etched onto its surface in the classical Sanskrit language, using the Brahmi script, provides the crucial clue to its origin.

The Gupta-Era Inscription

The inscription praises a powerful king named “Chandra”, celebrating his victories over his enemies in the Vanga country (modern Bengal) and his conquest across the “seven mouths of the Indus.” It states that he erected the pillar as a Vishnudhvaja—a standard or flagstaff dedicated to the Hindu god Vishnu—on a hill known as Vishnupada (“footprint of Vishnu”).

While the inscription doesn’t give a specific date, based on the script style and the king’s description, historians widely identify “Chandra” as the great Gupta emperor Chandragupta II Vikramaditya, who reigned from approximately 375 to 415 CE. His reign was a period of immense cultural, scientific, and artistic achievement, and the creation of such a metallurgical marvel fits perfectly within this historical context.

A Journey Through Time

The pillar did not always stand in its current location. It was moved to Delhi around the 13th century. It is believed that Anangpal, a Tomar king, first brought it to Delhi in the 11th century. Later, it was incorporated into the Quwwat-ul-Islam mosque, the first mosque built in Delhi, by Qutb-ud-din Aibak, the founder of the Delhi Sultanate. It was likely placed in the mosque’s courtyard as a trophy of war, a testament to the conqueror’s might, ironically preserving the very monument that celebrated a Hindu king.

For centuries, it has stood there, a silent witness to the rise and fall of empires, enduring Delhi’s monsoon rains, scorching summers, and polluted air with barely a trace of corrosion.

Unraveling the Rust-Proof Enigma

So, how did 4th-century blacksmiths create a virtually rust-proof iron pillar when modern iron structures require constant maintenance with paints and coatings to fend off corrosion? The answer is not a single “magic bullet” but a remarkable combination of material composition, craftsmanship, and environmental factors.

Dispelling the “Pure Iron” Myth

A common misconception is that the pillar is made of an incredibly pure form of iron, or perhaps even a mysterious alloy from a meteorite. Scientific analysis has thoroughly debunked this. The pillar is made of wrought iron with a purity of about 98%—a high quality for its time, but not exceptional by modern standards. The secret lies not in what was left out, but in what was left in.

The Secret Ingredient: Phosphorus

The key to the pillar’s longevity lies in its unusually high phosphorus content. Ancient Indian iron-smelting processes were different from modern methods. They used charcoal to smelt iron ore in small clay furnaces. This traditional method, known as “direct reduction”, did not completely liquefy the iron. The resulting spongy iron bloom was then repeatedly heated and hammered to expel slag and consolidate the metal.

Crucially, the specific iron ore and limestone flux used by the Gupta-era smiths contained high levels of phosphorus. Instead of being removed as impurities, a significant amount of this phosphorus (up to 1%) was incorporated into the final iron product. This “impurity” turned out to be a blessing.

Phosphorus acts as a catalyst, promoting the formation of an extremely thin, stable, and non-porous protective film on the surface of the iron. This passive layer, just a few micrometers thick, is a complex compound of iron, oxygen, and hydrogen, technically known as a crystalline iron hydrogen phosphate hydrate. This layer clings tightly to the metal, effectively sealing it off from the corrosive effects of air and moisture. Unlike common rust, which is flaky and porous and allows corrosion to continue unabated, this protective film self-heals and prevents any further degradation.

A Symphony of Factors

While high phosphorus content is the primary hero of this story, other factors play a supporting role:

- Expert Forging: The pillar was not cast as a single piece. It was painstakingly constructed by hammer-welding multiple hot iron blooms together. This process left behind microscopic slag inclusions, which help to break up the continuity of the iron and can also contribute to the formation of the passive layer.

- The Environment: Delhi’s climate, with its relatively low humidity for much of the year, is less corrosive than coastal areas. The pillar’s mass also allows it to retain heat, meaning that after a hot day, its surface stays warm longer than the surrounding air, preventing dew from condensing on it.

- A Human Touch (or Lack Thereof): For a long time, it was a tradition for visitors to stand with their backs to the pillar and try to encircle it with their hands for good luck. The oils and sweat from countless hands may have contributed to the surface patina. However, a fence was erected around the pillar in 1997 to protect it from this very contact, which was beginning to cause some discoloration and wear at the base.

Masters of the Forge

The Iron Pillar is more than just a chemical curiosity; it is a profound testament to the advanced skills of ancient Indian metallurgists. The sheer scale of forging a single, 6-ton piece of wrought iron was a monumental undertaking in the 4th century, requiring immense resources, manpower, and a deep, empirical understanding of materials science.

The creators of the pillar may not have known about phosphorus in the chemical sense, but through generations of trial and error, they mastered their craft. They knew which ores produced the most durable iron and perfected a forging process that resulted in a monument that would outlast their own empire by more than a millennium.

A Legacy Cast in Iron

Today, the Iron Pillar of Delhi stands as a link to a forgotten world of scientific achievement. It challenges the linear view of progress and reminds us that ancient civilizations possessed knowledge and skills that can still astound modern science. It is not an alien artifact or a product of lost magic, but the result of human ingenuity, masterful craftsmanship, and a deep harmony with the natural materials of the earth. It is a true metallurgical marvel, forever silent, forever strong, and almost, forever rust-free.