What’s in a Ceremony? The Roots of the Conflict

To understand the controversy, we first need to understand “investiture.” In the medieval feudal system, a lord would “invest” a vassal with symbols of his new office and land. For a knight, this might be a lance or a clod of earth. For a church official, like a bishop or an abbot, the symbols were a ring (representing spiritual marriage to the church) and a staff, or crosier (representing the shepherd’s duty to his flock).

For centuries, it was common practice for secular rulers, from local lords to the Holy Roman Emperor himself, to appoint these powerful churchmen. This practice was known as lay investiture. From the ruler’s perspective, this made perfect sense. Bishops and abbots weren’t just spiritual leaders; they were major landowners, controlled vast wealth, and were often the most literate and capable administrators in the kingdom. A king or emperor needed their loyalty and their resources. Appointing a loyal brother, a useful courtier, or the highest bidder to a bishopric was simply good politics.

But for a growing number of reformers within the Church, this was a spiritual cancer. The practice often led to:

- Simony: The outright buying and selling of church offices.

- Corruption: Appointees were often politicians or warriors, not pious men, leading to a decline in spiritual leadership.

- Divided Loyalties: Was a bishop a servant of God or a vassal of the king?

Beginning in the 10th century, a powerful reform movement, originating from the Abbey of Cluny in France, sought to purify the Church. They argued that for the Church to be the true vessel of God’s will on Earth, it must be free from the control of secular, or “lay”, rulers.

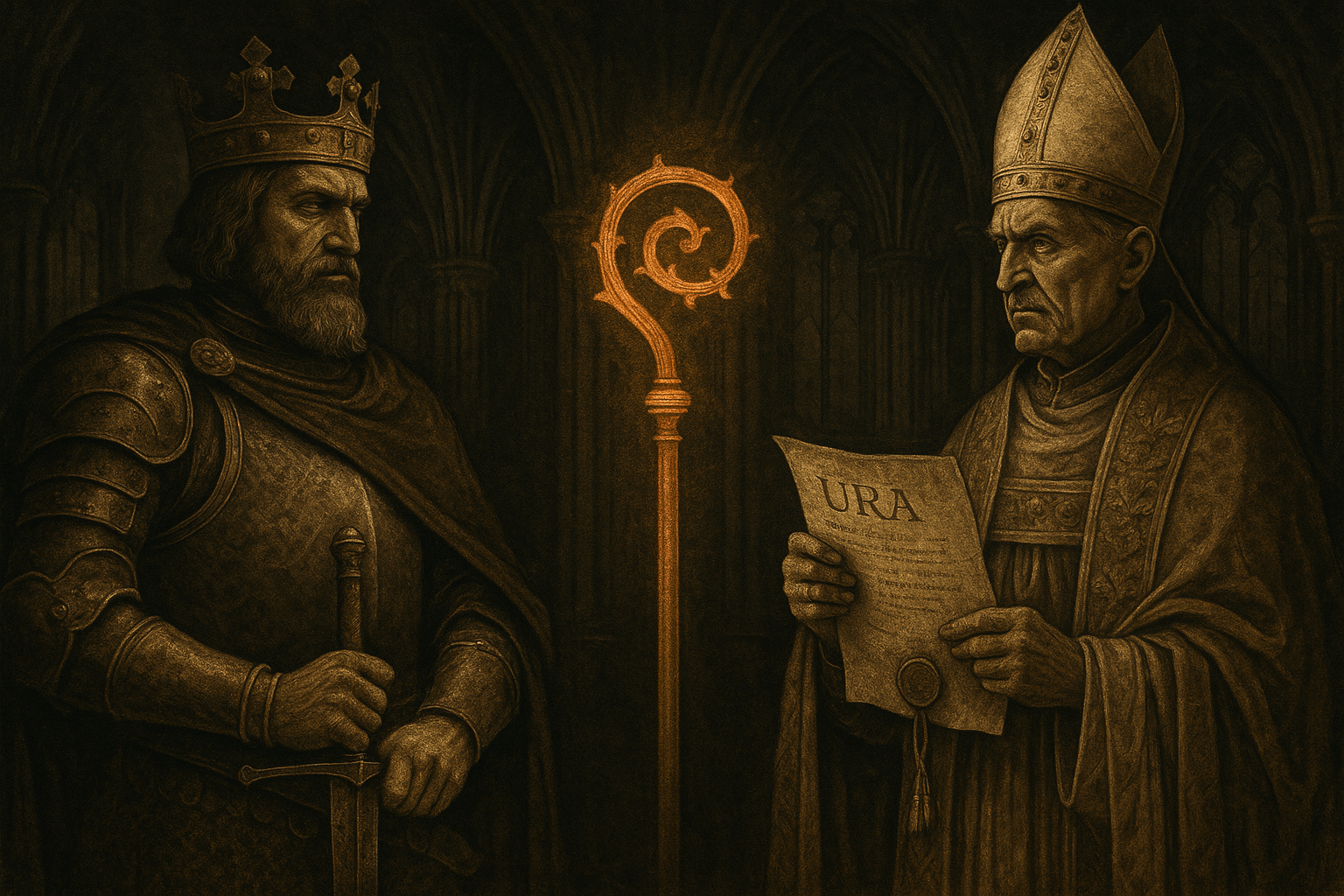

The Titans Clash: Pope Gregory VII vs. Emperor Henry IV

The simmering conflict boiled over in the 1070s with the rise of two formidable and unyielding figures. In one corner stood Pope Gregory VII, a brilliant and fiery reformer, formerly the monk Hildebrand. Gregory believed passionately in the absolute supremacy of the papacy. In his famous Dictatus Papae (Dictates of the Pope), a list of 27 propositions, he declared that the pope alone could appoint and depose bishops, and, most audaciously, that he had the power to depose emperors.

In the other corner was the young and headstrong Holy Roman Emperor, Henry IV. He had inherited the long-standing right of German emperors to appoint bishops throughout their lands, and he had no intention of surrendering this power, which was essential to his control over the rebellious German nobility.

The showdown began in 1075 when Gregory VII unequivocally banned lay investiture. Henry IV responded with defiance, appointing his own man to the powerful and wealthy position of archbishop of Milan. The Pope’s response was swift and devastating: in 1076, he excommunicated Henry IV. This was no mere spiritual slap on the wrist. Excommunication freed all of Henry’s vassals from their oaths of loyalty. The Emperor’s authority crumbled as his enemies at home, the German dukes, seized the opportunity to rebel, threatening to elect a new king.

The Walk to Canossa: A Masterclass in Political Theatre

Checkmated and facing the loss of his crown, Henry IV made a desperate, brilliant move. In the dead of winter in January 1077, he journeyed across the Alps to the castle of Canossa in northern Italy, where Pope Gregory was staying. For three days, the most powerful secular ruler in Christendom stood outside the castle gates, barefoot in the snow, dressed as a humble penitent, begging the Pope for forgiveness.

Gregory was caught in a bind. As a politician, he wanted to see Henry humbled and deposed. But as a priest, he was obligated to forgive any sinner who showed such profound penance. Reluctantly, Gregory lifted the excommunication. Henry had saved his throne.

While it appeared to be a victory for Henry in the short term, the image of an emperor humbling himself before a pope was a propaganda victory of immense proportions for the papacy. It cemented the idea in the public imagination that the Pope’s spiritual authority could bring even an emperor to his knees.

An Uneasy Truce: The Concordat of Worms

The drama at Canossa did not end the war. The conflict raged on for decades, with more excommunications, military campaigns, and the installation of “anti-popes” by the emperor. The struggle outlived both Gregory and Henry. Finally, after nearly 50 years of strife, a compromise was reached in 1122 with the Concordat of Worms (pronounced “Vorms”).

This agreement cleverly split the process of investiture in two:

- Spiritual Investiture: Churchmen would be freely elected (by other clergy) and invested with their symbols of spiritual authority—the ring and staff—by a representative of the Pope.

- Secular Investiture: The Emperor would then bestow upon the new bishop or abbot the symbols of his secular power—lands, titles, and political duties—by touching him with a scepter.

It was a compromise, but one that leaned heavily in the Church’s favor. The emperor had lost the power to pick his bishops, forever changing the balance of power.

The Lasting Legacy: A New Kind of World

The Investiture Controversy was more than just a feud between two powerful men. It fundamentally reshaped medieval Europe and cast a long shadow into the modern era. Its legacy is profound:

- It massively increased the power and prestige of the papacy, laying the groundwork for the “Papal Monarchy” of the High Middle Ages.

- It weakened the authority of the Holy Roman Emperor, contributing to the long-term political fragmentation of Germany and Italy.

- Most importantly, it drew the first clear, albeit messy, line between the powers of the church and the powers of the state.

The idea that spiritual and secular spheres should be separate was a radical concept in the 11th century. While the struggle for where that line should be drawn continues to this day, it was in the snows of Canossa and the halls of Worms that the debate first took center stage, forever changing the course of Western civilization.