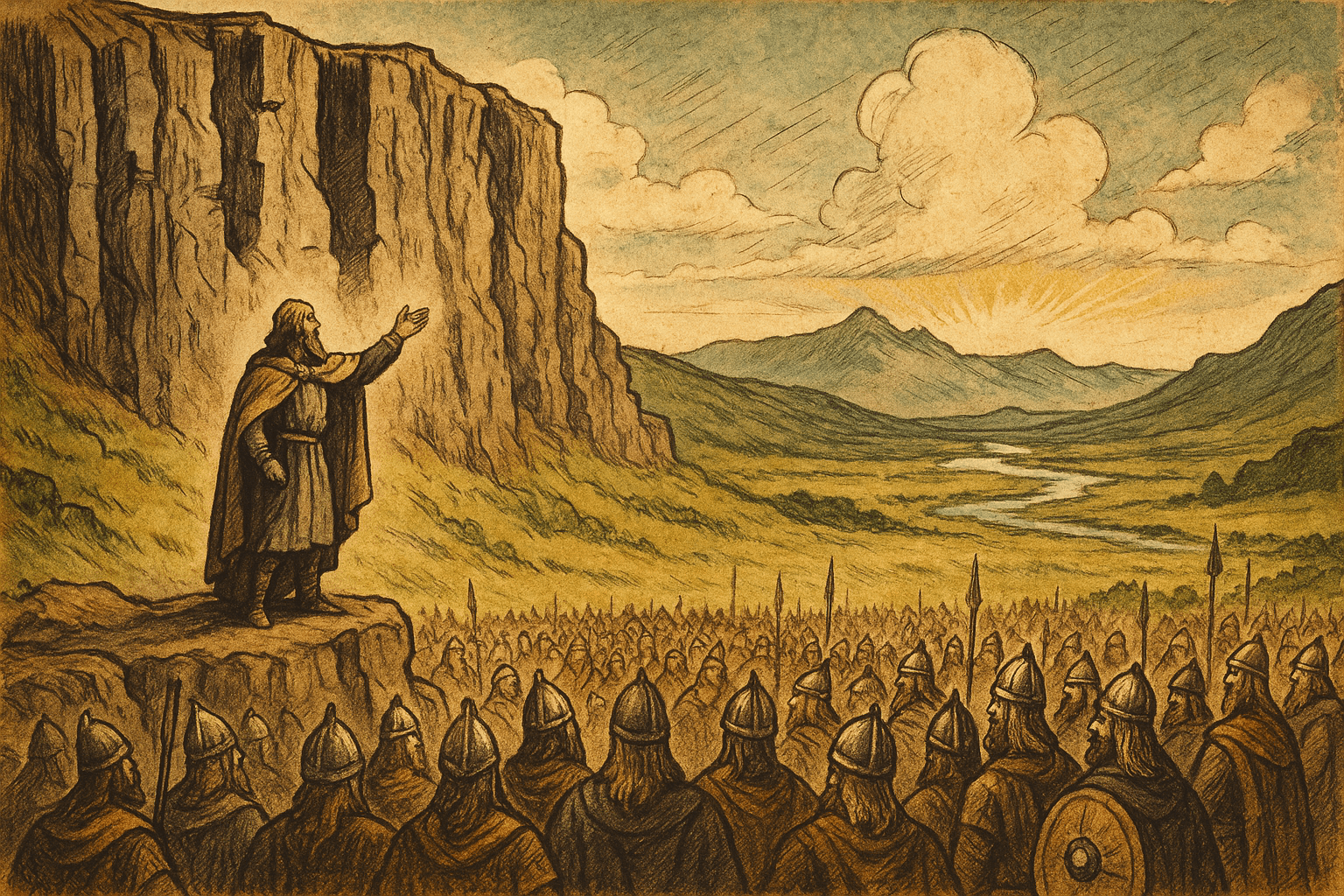

Picture a landscape torn from a saga. A vast, green plain sliced open by a dramatic cliff face—the edge of a tectonic plate. In this primordial valley, beneath a wide northern sky, thousands of people are gathered. Tents and turf booths cluster by a river, the air thick with the smoke of campfires, the murmur of law, and the din of commerce. This isn’t a scene of war, but of governance. This is 930 AD, and you are witnessing the birth of the Icelandic Althing (Alþingi), the world’s first national parliament.

A Nation Forged in Freedom

To understand the Althing, one must first understand how Iceland was settled. Beginning in the late 9th century, waves of Norse settlers, primarily from Norway, began sailing west. They were not just explorers; many were political refugees. They were chieftains (goðar), free farmers, and their families fleeing the ambitions of King Harald Fairhair, who was forcefully unifying Norway under his central rule. These were fiercely independent people, accustomed to governing their own affairs through regional assemblies, or things.

As Iceland’s population grew, so did the potential for conflict. Without a shared legal framework, disputes over land, livestock, or honor could easily spiral into violent, multi-generational blood feuds. A new, all-encompassing system was needed. The chieftains decided to create a commonwealth—a republic without a king, bound together by a common law. A wise man named Úlfljótr was reportedly sent to Norway to study its legal systems. Upon his return, the principles were adapted for Iceland, and a central location was chosen for a new, grand assembly: the Althing.

The Heart of the Commonwealth: Þingvellir

The site chosen was Þingvellir, the “Assembly Plains.” The location was no accident. Geographically, it was relatively accessible from all the major settlements of the time. Practically, it offered ample water from the Öxará river, grazing for horses, and wood for fires. Symbolically, its power was immense.

Þingvellir lies directly in a rift valley, marking the crest of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge where the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates are slowly pulling apart. The assembly literally took place on fractured ground, a poignant metaphor for a society determined to hold itself together through consensus and law. The main cliff, the Almannagjá (“Everyman’s Gorge”), created a spectacular natural amphitheater. It was from the Lögberg, or Law Rock, a prominent spot along this cliff, that the laws of the land would be proclaimed to all who gathered.

How Did the “Viking Democracy” Work?

The Althing was a complex system that balanced the power of chieftains with the rights of free men. It was less a democracy in the modern “one person, one vote” sense and more an aristocratic republic built on consent.

The Key Players

- The Goðar: There were initially 39 chieftains who held a goðorð, or chieftaincy. Crucially, a goðorð was not a piece of land but a political authority that was privately owned. It could be inherited, sold, or even shared. The farmers in a region, the þingmenn, swore allegiance to a goði and depended on him to represent them at the Althing. In a radical check on power, a free farmer could, at any time, switch his allegiance to a different goði. This kept chieftains accountable to their followers.

- The Lögsögumaður (Lawspeaker): The most prestigious position in the commonwealth was the Lawspeaker. Elected by the goðar for a three-year term, he was the living repository of Iceland’s laws. Each summer at the Althing, he was required to stand at the Law Rock and recite one-third of the legal code from memory. He presided over the assembly and was the ultimate interpreter of the law, but he had no power to rule or command.

The Institutions

The Althing was divided into two main parts. The Lögrétta, or Law Council, was the legislative heart. It was comprised of the goðar, each with two advisors, along with the Lawspeaker. This body had the power to create new laws and amend old ones. The second part consisted of the courts, which heard and passed judgment on disputes brought before the assembly.

One major weakness, however, was that the Althing had no executive branch. There was no king, no police force, no state-sanctioned authority to enforce the courts’ verdicts. If a person was found guilty, it was up to the wronged party and their kinfolk to carry out the sentence, whether it was seizing property as compensation or declaring the guilty party an outlaw, whom anyone could kill without penalty. This system, while brilliantly decentralized, often relied on personal power and could lead to the very feuds it was designed to prevent, as chronicled in the famous Icelandic Sagas like Njáls saga.

More Than Just Law: A Social and Cultural Hub

For the two weeks it was in session each summer, the Althing transformed Þingvellir into the temporary capital of Iceland. It was far more than a political assembly; it was the nation’s preeminent social event. People came from every corner of the island not just for justice, but to trade goods, arrange marriages, forge alliances, and share news from the farthest-flung fjords and from the world beyond.

It was a place for athletic contests, poetry recitals, and business deals. For a scattered and isolated population, the Althing was the glue that bound Iceland together, reinforcing a shared identity and culture year after year.

A Landmark Decision: The Conversion to Christianity

Perhaps the Althing’s finest hour came around the year 1000. Iceland was dangerously divided between its traditional Norse paganism and the growing influence of Christianity. With rival factions on the brink of civil war, a brilliant compromise was reached. Both sides agreed to let the pagan Lawspeaker, Þorgeir Ljósvetningagoði, decide the nation’s religious fate. After famously lying under a fur cloak for a day and a night to contemplate, he emerged and declared his verdict from the Law Rock: Iceland would officially become a Christian nation to maintain unity. However, in a display of remarkable pragmatism, he decreed that people could continue to worship the old gods in private. Civil war was averted not by a sword, but by the power of reasoned law and compromise.

The End of an Era and a Lasting Legacy

The Icelandic Commonwealth lasted for over 300 years. Over time, however, the system of competing goðar began to break down. Wealth and power concentrated in the hands of a few powerful families, leading to an era of civil war known as the Age of the Sturlungs. Weakened by internal strife, Iceland submitted to the authority of the Norwegian crown in 1262.

Though the Althing lost its legislative authority, it continued as a law court at Þingvellir until 1798. After a brief abolition, it was re-established in Reykjavík in 1845 and has served as Iceland’s modern parliament ever since, making it the oldest continuous parliamentary institution in the world.

Today, a visit to Þingvellir National Park is a journey into the heart of Iceland’s identity. Standing in that epic valley, you can still feel the echoes of the Lawspeaker’s voice and the weight of a society that, for three centuries, dared to govern itself not by the decree of a king, but by the power of a shared law spoken aloud in the wild heart of their nation.