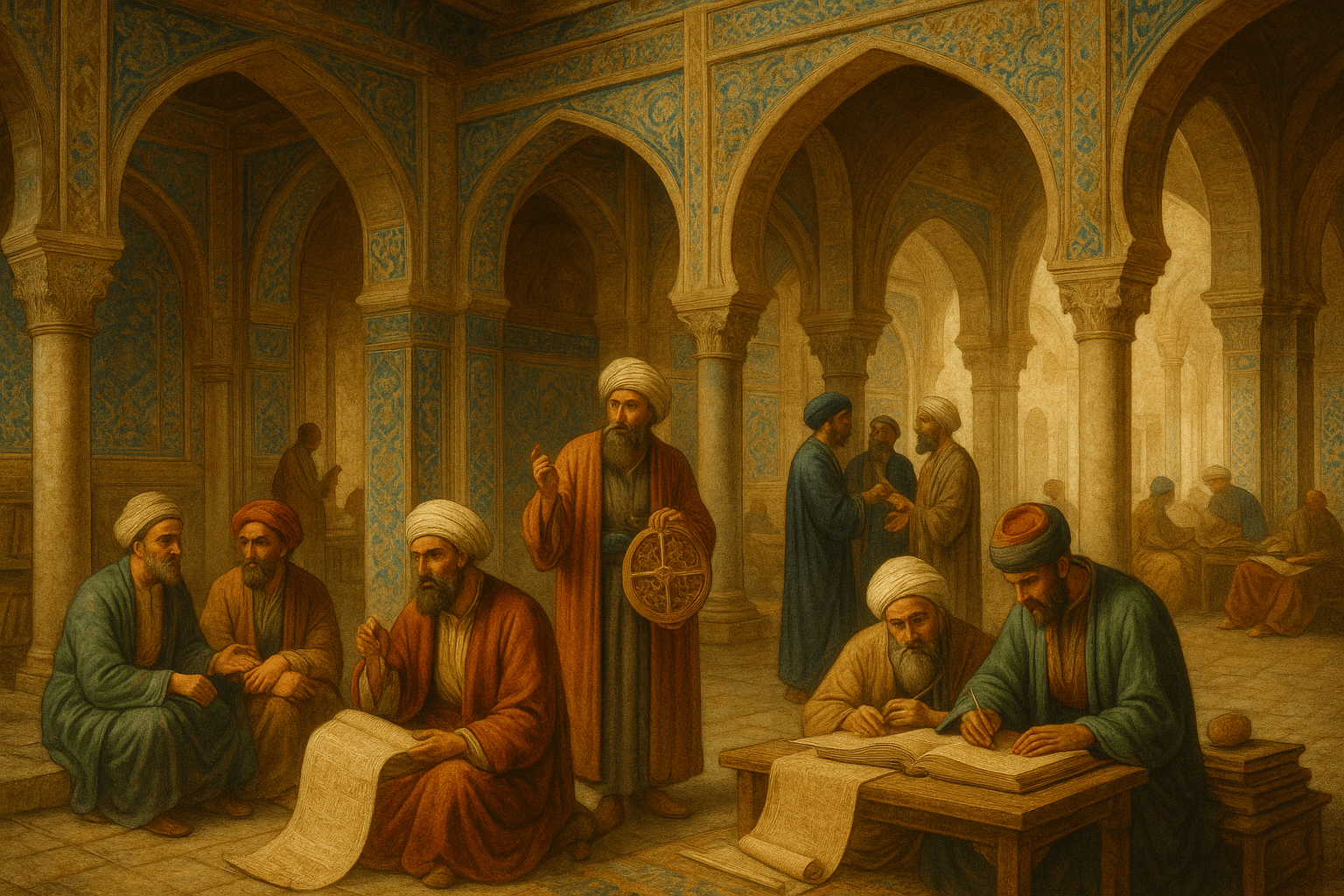

More than just a library, the House of Wisdom was a revolutionary institution—an academy, a translation center, and a research institute that became the epicenter of the Islamic Golden Age. It was a crucible where the knowledge of ancient civilizations was not only saved but synthesized and supercharged, ultimately preserving it for the entire world.

From a Private Collection to a Public Academy

The House of Wisdom didn’t appear overnight. Its origins lie with the powerful Abbasid Caliph Harun al-Rashid, a figure immortalized in the tales of One Thousand and One Nights. In the late 8th century, he established a palace library, the Khizanat al-Hikma (Library of Wisdom), to house a growing collection of manuscripts in various languages, including Persian, Greek, and Arabic.

However, it was his son, Caliph al-Ma’mun, who transformed this private collection into a world-changing public institution around 830 CE. Al-Ma’mun was a man consumed by a passion for knowledge and rational thought. He formally established the Bayt al-Hikma as a grand academy, funding it generously and drawing scholars to Baghdad like moths to a flame. His vision was clear: to gather all the world’s knowledge under one roof and make it accessible in the Arabic language.

The Great Translation Movement

The most crucial function of the House of Wisdom was its ambitious and systematic Translation Movement. This was an undertaking on an industrial scale. Al-Ma’mun and his successors dispatched agents across the Byzantine Empire and beyond, sending them to monasteries and libraries in search of manuscripts. They reportedly paid for texts with their weight in gold, and sometimes, the acquisition of philosophical or scientific works was even a condition of peace treaties.

Once secured, these treasures were brought back to Baghdad to be translated. The goal was to render the masterworks of human thought into Arabic, the era’s lingua franca of science and culture. The scope was breathtaking:

- From Greek: The philosophical works of Plato and Aristotle, the mathematics of Euclid, the astronomical models of Ptolemy, and the medical treatises of Galen and Hippocrates.

- From Persian: Literary classics, administrative techniques, and historical chronicles from the Sassanian Empire.

- From Sanskrit (India): Groundbreaking works on mathematics, astronomy, and medicine, including the introduction of what we now call “Arabic numerals” (which were originally Indian).

The translators themselves were a diverse group, reflecting the cosmopolitan spirit of the age. Nestorian Christians, Jews, and Muslims worked side by side. A standout figure was Hunayn ibn Ishaq, a Nestorian Christian physician and scholar. He was a master of four languages—Syriac, Arabic, Greek, and Persian. He led a team that translated over a hundred of Galen’s medical works, developing a rigorous methodology that involved comparing multiple manuscripts and creating a standardized Arabic vocabulary for scientific and medical terms. This wasn’t simple word-for-word translation; it was a scholarly act of interpretation and clarification.

More Than Just a Library

While translation laid the foundation, the true genius of the House of Wisdom was in what happened next. It was a vibrant research center where scholars didn’t just read the ancients; they debated, critiqued, corrected, and built upon them.

Attached to the great library were observatories, scriptoriums, and separate wings dedicated to different fields of study. Here, scholars made original contributions that would echo for centuries:

- In Mathematics, the brilliant scholar Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi synthesized Greek and Indian knowledge to create a new discipline. His book, Al-Kitāb al-mukhtaṣar fī ḥisāb al-jabr wa-l-muqābala (“The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing”), gave the world its first systematic guide to linear and quadratic equations. His title gave us the word “algebra” (al-jabr), and his own name, Latinized, gave us “algorithm.” It was also through his work that Hindu-Arabic numerals (0-9), including the revolutionary concept of zero, were introduced to the wider world.

- In Astronomy, scholars at the Baghdad observatory refined Ptolemy’s models of the cosmos, corrected his calculations, and created far more accurate astronomical tables (zij). They calculated the Earth’s circumference with an accuracy that was astonishing for its time.

- In Philosophy and a host of other sciences, thinkers like al-Kindi, the “philosopher of the Arabs”, worked to harmonize Greek philosophy with Islamic theology, pioneering new fields of inquiry in everything from optics to pharmacology.

The Seeds of a Renaissance

The knowledge nurtured in Baghdad did not remain sealed within its walls. As the Abbasid Caliphate’s influence spread, so did its intellectual wealth. This knowledge traveled west across North Africa and into Al-Andalus (Islamic Spain), where cities like Cordoba and Toledo became new centers of learning.

Centuries later, as European scholars sought to reconnect with their classical past, they found it waiting for them in Arabic. In cities like Toledo, Christian and Jewish scholars like Gerard of Cremona worked to translate these Arabic texts—which now contained the original Greek works enriched with centuries of commentary and new discoveries—into Latin. The reintroduction of Aristotle, Euclid, and Galen, through Arabic intermediaries, was a key spark that helped ignite the European Renaissance.

A Tragic End and an Enduring Legacy

The golden age could not last forever. Political fragmentation weakened the caliphate, and with it, the lavish patronage that had sustained the House of Wisdom. The final, devastating blow came in 1258 during the Mongol Siege of Baghdad. Hulagu Khan’s forces sacked the city, destroying monuments, palaces, and libraries.

A dramatic, if possibly apocryphal, account from the time claims that the invaders threw so many books from Baghdad’s libraries into the Tigris River that its waters ran black with ink for days. Whether literal or symbolic, this image captures the immense cultural tragedy of the loss. The physical House of Wisdom was gone.

But its spirit was not. The Bayt al-Hikma stands as a powerful testament to the universal human quest for knowledge and the incredible heights that can be reached through cross-cultural collaboration. It reminds us that no single civilization has a monopoly on wisdom and that the preservation and advancement of knowledge is a shared global inheritance. The light that shone so brightly in 9th-century Baghdad had already illuminated a path for the rest of the world to follow.