Who Were the Hopewell Peoples?

It’s important to understand that “Hopewell” was not a single tribe, empire, or nation. There was no Hopewell king ruling from a central capital. Rather, the term describes a widespread set of shared cultural practices, rituals, and artistic styles that flourished from roughly 100 BCE to 500 CE. The epicenter of this tradition lay in the river valleys of what is now southern Ohio, but its influence radiated outwards for thousands of miles.

The people of the Hopewell tradition lived in semi-permanent settlements, relying on a mix of hunting, gathering, and the cultivation of native plants like squash, sunflower, and maygrass—an agricultural system known as the Eastern Agricultural Complex. But they are most famous for their monumental public works: massive, geometrically precise earthworks. Sites like the Newark Earthworks in Ohio feature enormous circles, octagons, and squares aligned with stunning astronomical precision. These were not cities in the modern sense, but vast ceremonial centers where dispersed communities would gather for religious festivals, intricate burial rituals, and, crucially, to participate in continent-spanning trade.

Arteries of a Continent: The Hopewell Exchange Network

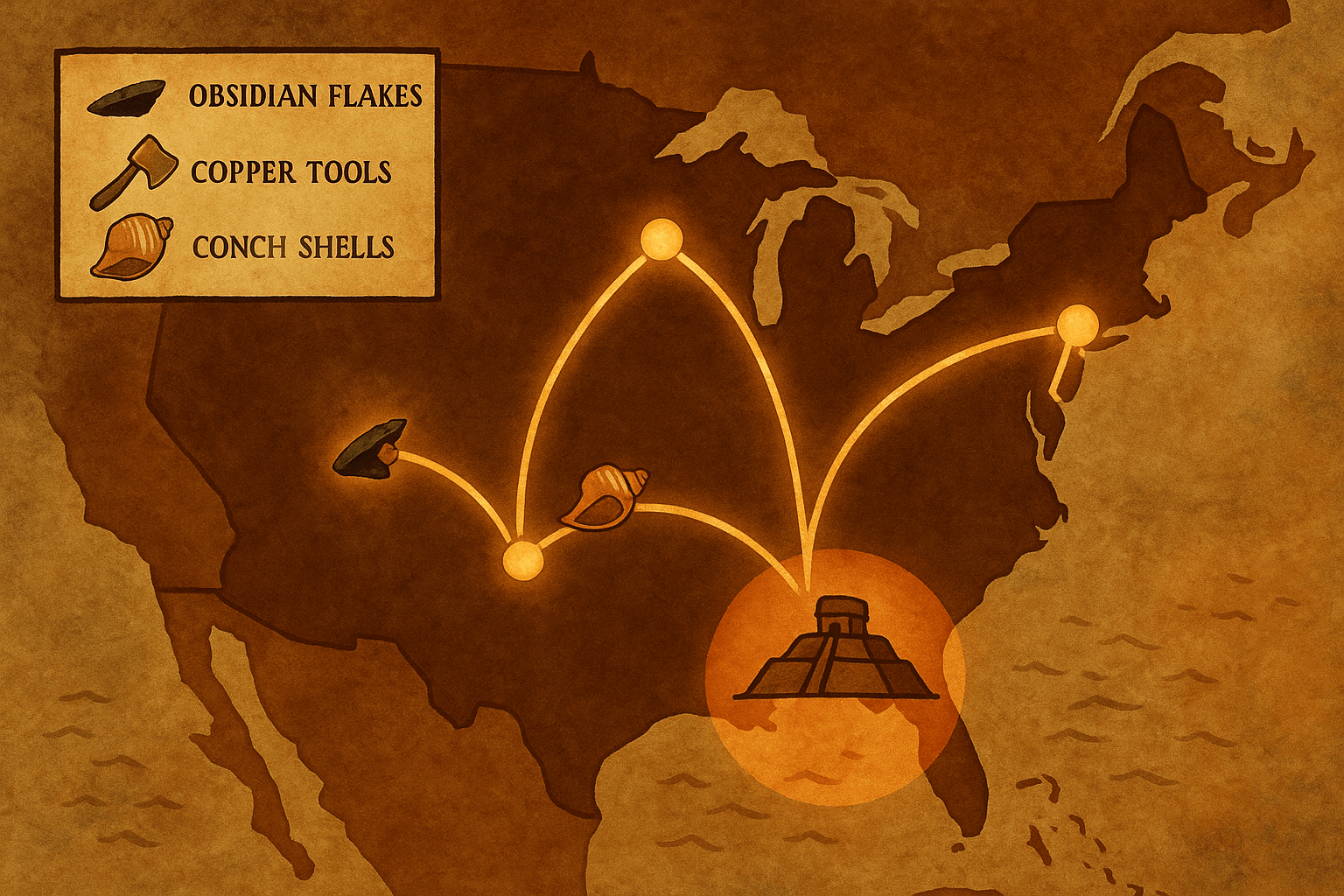

At the core of the Hopewell tradition was the “Hopewell Exchange Network”—a testament to the ambition, mobility, and organizational power of these ancient peoples. The network moved raw materials and finished goods over astonishing distances. These were not everyday commodities; they were rare, exotic, and spiritually potent materials, reserved for ceremonial use and to signify the status of important individuals.

The sheer scale of this trade is breathtaking. Consider the materials uncovered by archaeologists in the burial mounds of Ohio chieftains and shamans:

- Copper: Sourced from the Great Lakes region, particularly the Keweenaw Peninsula of Michigan and Isle Royale. Hopewell artisans cold-hammered this metal into elaborate breastplates, intricate ear spools, ceremonial axes (celts), and animal-effigy ornaments.

- Mica: This shimmering, silicate mineral was mined in the southern Appalachian Mountains of North Carolina. It was painstakingly cut into delicate and complex shapes, including human hands, bird talons, and serpents, likely used in sacred regalia.

- Obsidian: Perhaps the most stunning example of long-distance trade, this black volcanic glass has been chemically traced to sources in Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming. From there, it traveled over 1,500 miles to Ohio, where it was masterfully flaked into massive, beautiful, but non-utilitarian ceremonial blades, some over a foot long.

- Marine Shells: Large conch and whelk shells were brought inland from the coast of the Gulf of Mexico. They were carved into elaborate pendants known as gorgets or used as sacred drinking cups in rituals.

- Grizzly Bear Teeth and Shark Teeth: Evidence of a continental reach, grizzly bear canines from the Rocky Mountains and shark teeth from the Atlantic coast were drilled and used as powerful pendants and ornaments, imbued with the spirit of these formidable animals.

This was not simple bartering between neighboring villages. The existence of such a widespread network implies sophisticated relationships, established trade routes, and a shared understanding of the value—both material and spiritual—of these exotic goods.

More Than Goods: A Marketplace of Ideas

The Hopewell Exchange Network was about more than just moving physical objects. It was a conduit for the flow of information, technology, and belief. As materials moved from hand to hand, so too did artistic styles and religious concepts. Archaeologists refer to this as the “Hopewell Interaction Sphere.”

An artisan in Illinois might see a design on a copper plate from Ohio and incorporate it into their own local pottery traditions. A mortuary ritual practiced in the Scioto River Valley might be adopted and adapted by communities hundreds of miles away. This is why we see a distinct “Hopewell style” across a vast area: elegant platform pipes carved into hyper-realistic animal forms, pottery stamped with complex geometric and curvilinear designs, and shared symbols like the raptorial bird or the serpent.

The network created a common cultural and religious language that transcended local identities. It fostered a shared cosmology, allowing people from vastly different environments and backgrounds to participate in a collective spiritual landscape. The exotic materials, carried over immense distances, were tangible proof of this interconnected world, symbols of power derived not just from wealth, but from access to a wider sacred geography.

The End of an Era

Around 400-500 CE, this grand system began to wane. The construction of monumental earthworks ceased, and the flow of exotic goods slowed to a trickle. This was not a sudden “collapse” or the disappearance of a people. Rather, it was a profound cultural shift.

Archaeologists debate the exact causes. Colder, less predictable climate patterns may have stressed the native food systems. The introduction and spread of the bow and arrow may have altered patterns of warfare and hunting, leading to more localized and defensive societies. Another compelling theory suggests that as maize (corn) agriculture became more dominant, societies became more sedentary and territorial. The focus shifted from the prestige of long-distance spiritual goods to the control of fertile farmland, unraveling the very foundation of the Hopewell network.

The legacy of the Hopewell did not vanish. It evolved, laying the cultural groundwork for the subsequent Mississippian cultures, including the builders of the great city of Cahokia. But the Hopewell Exchange Network remains a singular achievement—a powerful reminder that the history of North America is one of ancient complexity, deep spiritualism, and profound interconnectedness, written not in books, but in the earth and in the remarkable artifacts left behind.