Close your eyes and imagine a world without a synchronized clock. A world where a ten-mile journey could send you spiraling through a dozen different “correct” times. In this world, the time in Philadelphia is not the time in Harrisburg. Noon is simply the moment the sun reaches its highest point in the sky, a purely local event. For most of human history, this was reality. But the arrival of a new, earth-shaking technology—the railroad—would make this solar-powered chaos untenable, forcing humanity to finally agree on what time it is.

A World of a Thousand Clocks: The Chaos of “Sun Time”

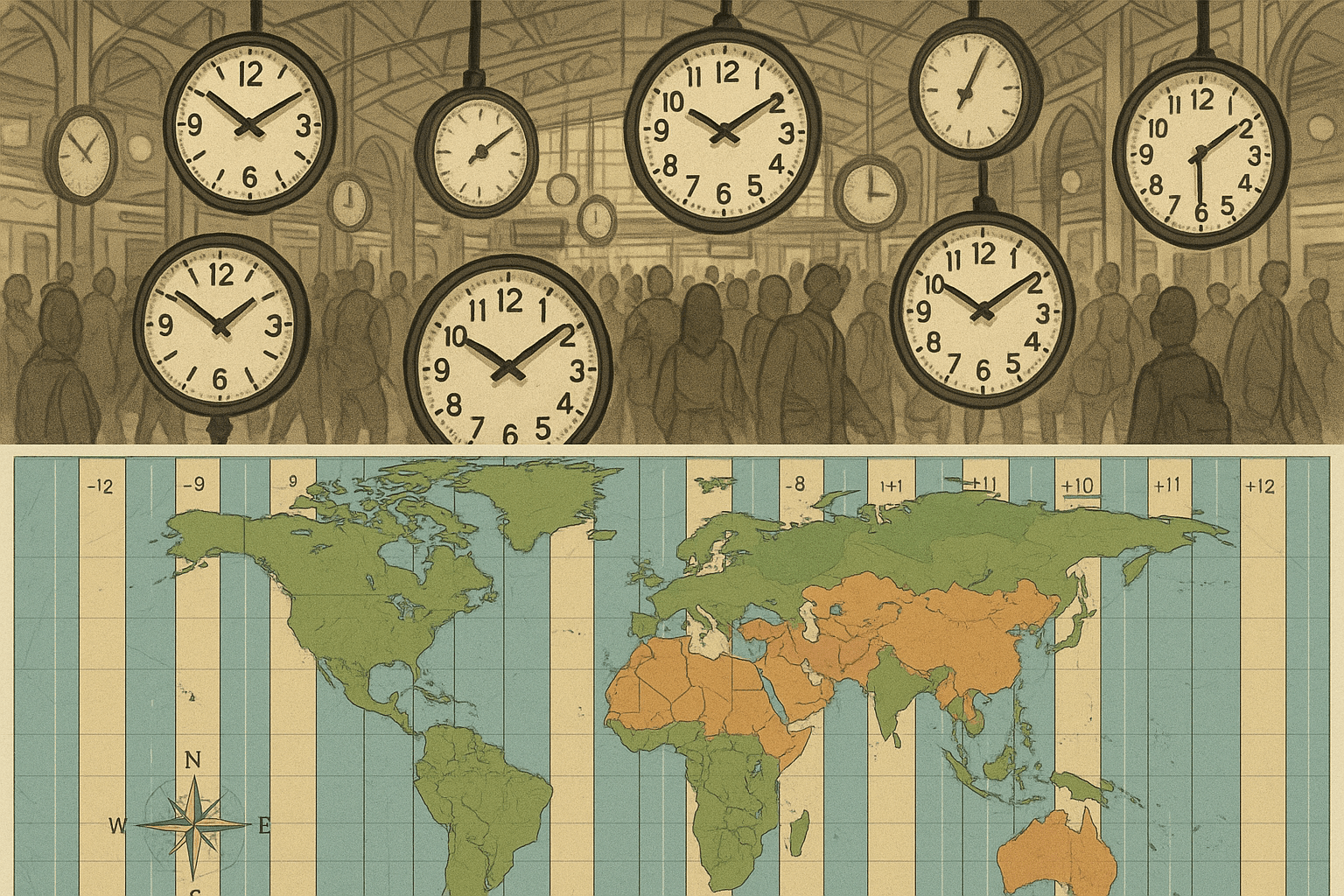

Before the mid-19th century, time was a local affair. Each town, village, and city set its clocks according to its own local mean solar time. When the sun was directly overhead, it was noon. This system worked perfectly well for millennia. When the fastest you could travel was the speed of a horse, the few minutes’ difference between one town and the next was unnoticeable and irrelevant.

By the 1870s, however, the United States was a patchwork of temporal confusion. There weren’t just a handful of different times; there were thousands. Indiana alone officially observed over 20 different local times. A traveler going from Maine to California might have to adjust their watch over 200 times. A government report from the era listed over 300 different local times in use by American towns and cities. For the average citizen, this was a quirky inconvenience. For the burgeoning railroad industry, it was a logistical nightmare that threatened the safety and efficiency of the entire enterprise.

The Iron Horse and the Tyranny of the Timetable

The railroad was the internet of its day—a revolutionary technology that compressed space and time. Suddenly, a journey that once took weeks by wagon could be completed in a matter of days. But to operate this vast network of iron and steam, the railroads needed one crucial document: the timetable.

How could a railroad company create a coherent schedule when every station operated on its own clock? Imagine a train scheduled to leave Chicago at 10:00 AM and arrive in Fort Wayne, Indiana, at 1:00 PM. But which 10:00 AM? Chicago’s? And which 1:00 PM? Fort Wayne’s? The railroads tried to manage this by publishing complex timetables with conversion charts, often with dozens of columns of arrival and departure times for a single train, each corresponding to a different local time. It was baffling for passengers and dangerously confusing for conductors and engineers.

The consequences were more than just missed connections. They were deadly. Without a single, reliable time standard, the risk of head-on collisions on single-track lines was immense. A conductor in one town might believe he had ten minutes to get his train onto a siding, while an oncoming train’s conductor, operating on a clock just a few minutes different, believed he had the right of way. While many accidents occurred, one tragic event in Kipton, Ohio, in 1891 brutally highlighted the stakes. Two trains collided head-on after one of the engineers’ watches had stopped for four minutes and then restarted, making him believe he had more time than he actually did. The incident became a powerful argument for a uniform time standard that could be checked and maintained with precision.

The Visionaries: From Schoolmaster to Railway Engineer

The problem was so obvious that several minds began working on a solution. One of the earliest pioneers was a school principal named Charles F. Dowd. In 1870, he proposed a system of four standard time “belts”, or zones, for the United States, centered on the meridians of Washington, D.C., and New Orleans. Though his plan was initially ignored, he had planted the seed of the idea that would eventually take root.

The man most credited with championing the cause on an international scale was Sir Sandford Fleming, a Scottish-born Canadian railway engineer. The story goes that Fleming’s “eureka” moment came in 1876 after he missed a train in Ireland because the schedule printed “p.m.” instead of “a.m.” This personal frustration drove him to tackle the larger, systemic problem of time itself.

Fleming proposed a plan for a worldwide standard time, which he called “Cosmic Time.” His vision was comprehensive: a single, 24-hour clock for the entire planet, based on a prime meridian (0° longitude). From this starting point, the world would be divided into 24 time zones, each one hour apart. While the idea of a single global clock was too radical, the core concept of a universal prime meridian and hourly zones was brilliant.

The Day of Two Noons: The Great Switchover

Frustrated by government inaction, the American railroad companies decided to take matters into their own hands. At the General Time Convention in Chicago in October 1883, railway managers from across the United States and Canada adopted a plan based on the proposals of Dowd and Fleming. They established five time zones for North America: Intercolonial (what we now call Atlantic), Eastern, Central, Mountain, and Pacific. The switchover was set for a specific, coordinated moment.

That moment came at noon on Sunday, November 18, 1883. It was dubbed “The Day of Two Noons.” As telegraph signals transmitted the exact time from the Allegheny Observatory in Pittsburgh, cities and towns across the continent paused. In cities on the eastern edge of a new time zone, the clocks were moved back several minutes. As noon according to the old “sun time” came and went, citizens waited for the new, standardized noon to arrive. In other places, clocks were moved forward. Jewelers hung signs offering to adjust timepieces, and newspapers ran detailed explanations of the change.

There was resistance, of course. Some decried “railroad time” as an arrogant imposition, an unnatural violation of “God’s time.” The mayor of Bangor, Maine, famously protested, refusing to adopt a system that would make his city obey the time of a meridian 500 miles away. But the power and utility of the railroads won out. The logic was undeniable, and within a year, over 85% of American cities with populations over 10,000 had adopted the new system.

From Railroad Time to World Time

The success of the North American experiment paved the way for a global standard. In October 1884, President Chester A. Arthur convened the International Meridian Conference in Washington, D.C. Delegates from 25 nations gathered to choose a prime meridian for the world and establish a universal system of timekeeping.

After weeks of debate, they voted to establish the meridian passing through the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, England, as the Prime Meridian (0° longitude). This decision officially established Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) as the world’s time standard, and the 24-zone system proposed by Fleming was endorsed as the framework for global time.

Yet, just as it had in the U.S., official government adoption lagged behind practical use. It wasn’t until the Standard Time Act of 1918 that the U.S. government officially sanctioned the railroad time zones. Today, the system they built underpins everything we do. From coordinating international flights and global financial markets to scheduling a Zoom call with someone across the ocean, we rely on this invisible framework born from the smoke, steel, and steam of the 19th-century railroad.