Standing in a modern airport queue, you clutch a small, durable booklet. Its cover bears the coat of arms of your country, its pages a stamped mosaic of your travels. This document—your passport—feels like an immutable fact of modern life, the essential key to unlocking the world. Yet, this powerful little book is a relatively recent invention, the product of a long and fascinating evolution from a simple royal letter to a high-tech tool of global governance. How did we get from a handwritten note ensuring safe passage to a biometric chip containing your unique identity?

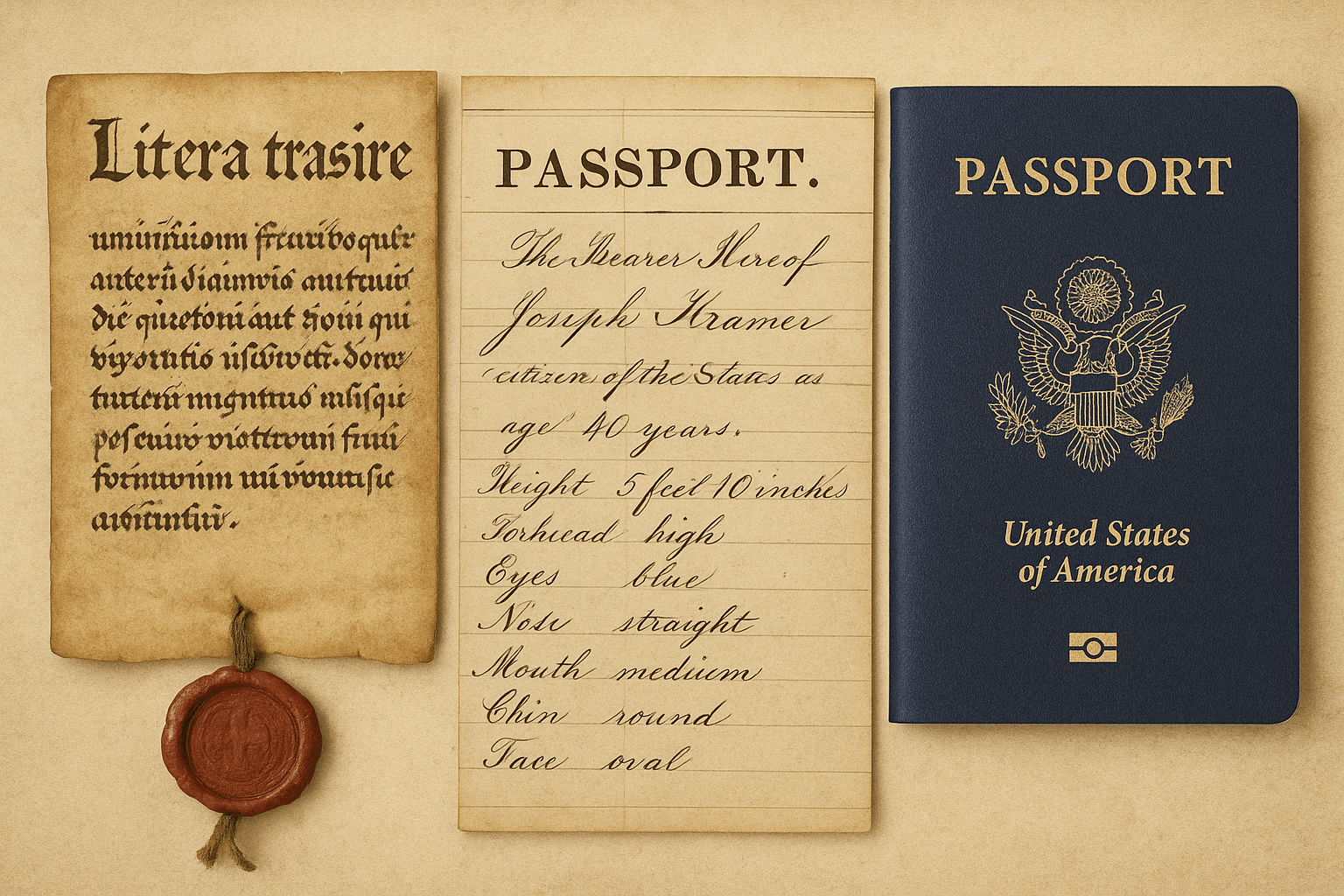

The First ‘Passports’: Letters of Safe Conduct

The core idea of a passport—a document requesting that its holder be allowed to pass without harm—is ancient. One of the earliest known references can be found in the Hebrew Bible, in the Book of Nehemiah, written around 450 BC. Nehemiah, an official serving King Artaxerxes I of Persia, wishes to travel to Judea and asks the king for assistance:

“And I said to the king, ‘If it pleases the king, let letters be given me to the governors of the province Beyond the River, that they may let me pass through until I come to Judah.’”

These “letters” were essentially safe-conduct passes. They weren’t a form of national identification but a request from one sovereign to another, granting protection to a specific individual on a specific mission. For centuries, this remained the basic model. In Roman times, the declaration “Civis Romanus sum” (“I am a Roman citizen”) served a similar purpose, carrying with it the protection and authority of the Empire, though it was a statement of status rather than a physical document.

Passing Through the Port: The Medieval Passport

The term “passport” itself likely emerged in the medieval period, though its exact origins are debated. The most common theory is that it derives from the French passe port, meaning “to pass through a port” or a city gate. These documents were not for the average person, who rarely traveled far from their village. Instead, they were granted by monarchs or local lords to a select few: diplomats, royal messengers, soldiers, and prominent merchants.

One of the first rulers to formalize this system was King Henry V of England in the early 15th century. An Act of Parliament in 1414 empowered the King to issue “safe conducts”, which we would now recognize as early passports, to his subjects traveling abroad. These were typically single, large sheets of paper, signed by the monarch, and often included a physical description of the bearer. You might be described as “tall, with a grey beard and a scar on his left cheek”—a rudimentary form of biometric identification.

The Great Turning Point: World War I and the Lockdown of Borders

For much of the 19th and early 20th centuries, international travel for many Europeans and Americans was surprisingly free. The rise of railways had made crossing borders easier than ever, and in many places, passports were considered an archaic annoyance. You could often buy a train ticket from Paris to St. Petersburg and travel across the continent with little more than your ticket and some currency.

World War I changed everything. Suddenly, the free movement of people across borders was no longer a sign of progress but a grave security threat. Nations, gripped by paranoia over espionage and subversion, slammed their borders shut. Requiring travelers to carry a passport from their home country became a “temporary” wartime measure to track who was coming and going. For the first time, a passport began to shift from a letter of introduction for the elite to a compulsory document of identity and citizenship for the masses.

When the war ended, these temporary measures didn’t disappear. The passport had proven to be an incredibly effective tool for state control. Governments realized its power not only for security but also for regulating immigration, controlling dissent, and cementing the concept of national belonging. The age of casual, passport-free travel was over for good.

Forging a Global Standard

The post-war world was a mess of conflicting travel document requirements. Every country had its own idea of what a passport should look like, what information it should contain, and what languages it should use. The chaos hindered trade, diplomacy, and the simple act of travel.

Recognizing the problem, the newly formed League of Nations held the Paris Conference on Passports & Customs Formalities and Through Tickets in 1920. This landmark conference laid the foundation for the modern passport system. Its key recommendations included:

- A standardized format: a booklet of a specific size (15.5 cm x 10.5 cm).

- A 32-page layout, with the first four pages for personal details and the remainder for visas.

- The title “Passport” should be written in the national language and in French.

- The inclusion of a photograph of the bearer.

While adoption was gradual, the 1920 agreement created the blueprint for the familiar little book that travelers would carry for the rest of the 20th century.

From Photo ID to Microchip: The Modern Passport Evolves

The 20th century saw further refinements driven by technology and security concerns. After World War II, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), a UN agency, took over the role of setting passport standards to facilitate air travel. In the 1980s, the ICAO introduced the Machine Readable Passport (MRP), featuring the now-ubiquitous two lines of letters, numbers, and chevrons at the bottom of the photo page. This Machine Readable Zone (MRZ) allowed for automated scanning, dramatically speeding up border crossings and improving accuracy.

The next great leap was a response to another global crisis: the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. Security became the paramount concern in international travel. This led to the development of the biometric passport, or e-Passport, which is the current global standard. These passports look much like their predecessors but contain a hidden electronic chip. This chip securely stores a digitized version of the holder’s photograph, the information on the data page, and, in many countries, biometric data like fingerprints or iris scans. This makes the document exceptionally difficult to forge and allows for verification against a traveler’s actual physical features.

From a handwritten plea for safe passage to a cryptographically-secured microchip, the passport’s history mirrors our world’s own journey. It tells a story of expanding empires, the rise of the nation-state, the trauma of global wars, and the relentless advance of technology. Today, it is more than just a travel document; it is the primary physical proof of our identity and citizenship, a small book that holds immense power over where we can go and who we are in the eyes of the world.