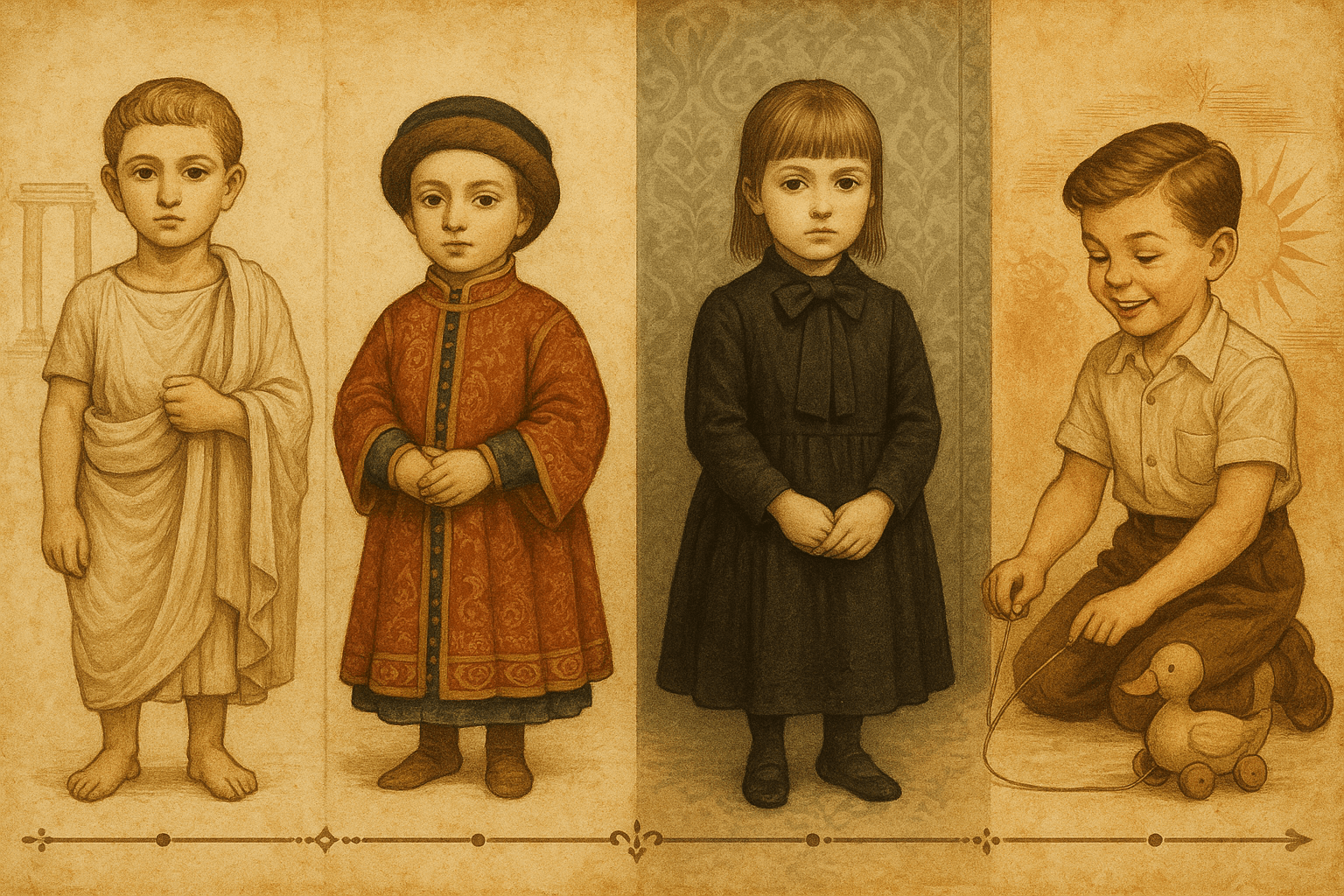

Not Seen, Not Heard: Children in Antiquity and the Middle Ages

Journey back to ancient Greece or Rome, and you would find a world with a startlingly unsentimental view of children. In the Roman household, the pater familias, or father of the family, held the power of life and death over his newborn children. While deep parental affection certainly existed, high infant mortality rates—where perhaps only half of children reached the age of ten—necessitated a degree of emotional distance. Children were seen not as unique beings in a special phase of life, but as incomplete adults, potential future citizens, or heirs who needed to survive to be of value.

This perspective arguably became even more pronounced in the Middle Ages. The influential historian Philippe Ariès famously argued that in medieval society, the very concept of childhood “did not exist.” This doesn’t mean children were unloved, but that as soon as they could live without constant care (around age seven), they were absorbed into the adult world. They wore smaller versions of adult clothing, worked alongside their elders in fields and workshops, and participated in the same festivals, taverns, and even criminal proceedings. They were, in essence, miniature adults, exposed to all the hardships, vulgarities, and realities of medieval life.

A Soul to Be Molded: The Renaissance and Reformation

The first shifts in this worldview began to appear during the Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation. A renewed interest in classical education led humanist thinkers to focus on the proper instruction of (primarily elite, male) children to create ideal citizens. Simultaneously, religious reformers like Martin Luther and John Calvin introduced a new moral urgency to child-rearing.

They saw children not as innocent, but as born with original sin—tiny, flawed vessels that needed to be strictly disciplined and morally corrected to be saved. This period saw the proliferation of catechisms and moral guidebooks. The goal was not to nurture a child’s unique spirit but to break their sinful will and mold them into pious, obedient adults. Childhood became a probationary period, a spiritual bootcamp for the soul.

The Great Invention: The Enlightenment and the Romantic Child

The true revolution in the history of childhood began in the 17th and 18th centuries. The Enlightenment brought two monumental ideas that would forever change how the Western world saw its children.

- John Locke (1690s): In his Some Thoughts Concerning Education, the English philosopher proposed that a child’s mind is a tabula rasa, or “blank slate.” He argued that children are not born inherently good or evil, but are shaped entirely by their environment and experiences. This placed an immense new responsibility on parents and educators to provide a positive and rational upbringing.

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1762): The French thinker went even further in his seminal work, Emile, or On Education. Rousseau passionately argued that children are born inherently good and innocent, and that it is society that corrupts them. He idealized childhood as a pure, natural state, a “noble savage” that should be allowed to develop freely, away from the constricting influence of adult conventions.

These ideas laid the intellectual groundwork for our modern concept of childhood. The Romantics of the early 19th century, like the poet William Wordsworth, fully embraced Rousseau’s vision, celebrating the child as a symbol of spiritual purity, imagination, and closeness to God and nature.

The Victorian Paradox: An Idealized Prison

The 19th century witnessed a strange and often brutal contradiction. Among the rising middle classes, the Romantic ideal of childhood flourished. The family home became a sacred, private sphere designed to shield the “innocent” child from the harsh realities of the outside world. A whole new market for children’s books, toys, and clothing emerged, cementing childhood as a special, protected, and desexualized stage of life.

Yet, at the very same time, the Industrial Revolution was thrusting millions of working-class children into the most horrific conditions imaginable. Children as young as five worked long, dangerous hours in coal mines, textile factories, and as chimney sweeps. This stark duality—the cherished middle-class child versus the exploited working-class laborer—eventually sparked reform movements. The first laws regulating child labor and promoting compulsory education were not just about protecting children, but about defining who was allowed to *have* a childhood in the first place.

The Century of the Child

The 20th century saw the consolidation of the modern, Western model of childhood. The emerging fields of developmental psychology and pediatrics, led by figures like Sigmund Freud and Jean Piaget, scientifically categorized childhood into distinct developmental stages. Education became a universal and compulsory experience, and the state increasingly took on a role in protecting children’s welfare.

By the end of the century, this ideal was codified on a global scale with documents like the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), which defines childhood as a time for play, education, and protection. The “invention” was complete. The journey from a miniature adult to a psychologically complex and legally protected individual had taken centuries.

Today, as we navigate the challenges of the digital age and increasing global awareness, our understanding of childhood continues to evolve. But by looking back, we can appreciate that the world we build for our children is not a given. It is a choice—a reflection of our deepest cultural values, fears, and aspirations.