A Collision Course in a Wartime Harbour

The tragedy began with two ships on intersecting paths in “The Narrows”, the tight channel connecting the outer harbour to the Bedford Basin. The first was the SS Imo, a Norwegian vessel chartered to pick up relief supplies for war-torn Belgium. Unladen and riding high in the water, she was impatient to depart after delays.

The second, heading into the harbour, was the SS Mont-Blanc, a French cargo ship. To an outside observer, she seemed unremarkable. But below her decks, she was a floating bomb. Her hold was packed with a highly volatile cocktail of military explosives:

- 2,300 tons of wet and dry picric acid

- 200 tons of TNT

- 10 tons of guncotton

- 35 tons of benzol, a flammable fuel, stored in barrels on the deck

Due to the explosive nature of her cargo, the Mont-Blanc was not flying the customary warning flags, hoping to avoid becoming a target for German U-boats. A series of misunderstood signals, poor navigation in the crowded channel, and a fateful last-minute maneuver resulted in the Imo striking the Mont-Blanc on her starboard bow at low speed. The impact itself was not severe, but it was enough. Barrels of benzol toppled, spilling their contents across the deck. When the steel hulls scraped against each other, the resulting sparks ignited the volatile fuel. A fire began to rage.

The Calm Before the Cataclysm

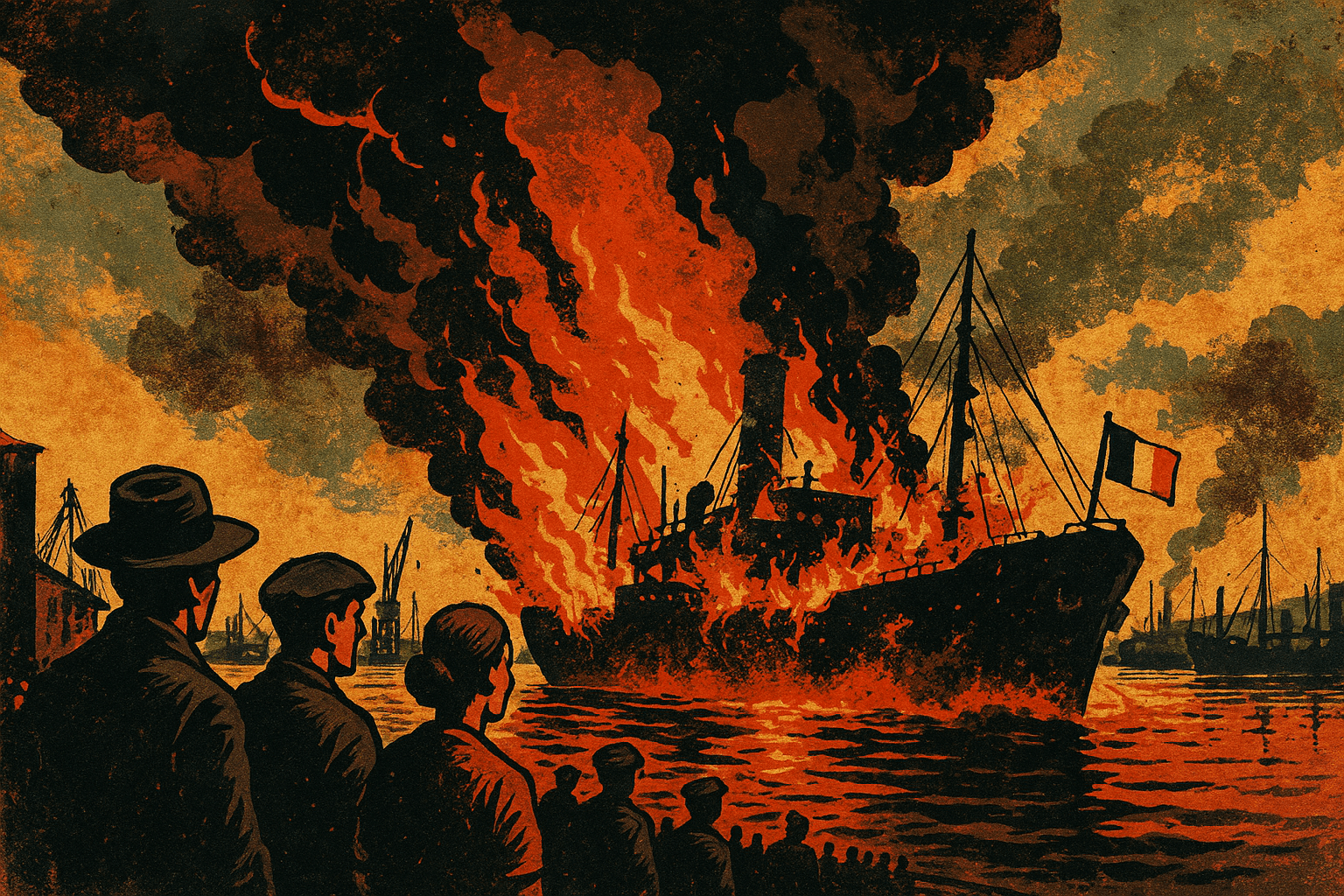

Knowing the apocalyptic potential of the fire, the captain and crew of the Mont-Blanc immediately abandoned ship, rowing desperately for the Dartmouth shore while shouting warnings that few could understand or hear. The burning, unguided vessel drifted toward the Halifax waterfront, coming to rest against Pier 6 in the city’s industrial Richmond district.

Onlookers gathered by the waterfront and in the windows of their homes and offices, mesmerized by the spectacle of the burning ship. Children on their way to school stopped to watch. Firefighters, including Halifax’s first motorized fire engine, the Patricia, raced to the scene, unaware that they were driving into an inescapable trap. They prepared to douse a ship fire, believing it was the worst they would face that day. They had no idea they were about to be vaporized.

9:04:35 AM: A City Erased

At 9:04 and 35 seconds AM, the Mont-Blanc’s cargo detonated. The result was instantaneous and absolute devastation. The ship was obliterated in a blinding white flash, and a fireball rose over 1.6 kilometers (1 mile) into the air, creating the now-familiar mushroom cloud. The temperature at the blast’s core reached an estimated 5,000°C (9,000°F).

A ferocious pressure wave radiated outwards, traveling faster than the speed of sound. It flattened virtually every structure within a 2.5-square-kilometer (1-square-mile) radius, an area that encompassed the entire Richmond district. Buildings, factories, and homes were reduced to splinters. The blast generated a deafening roar that was heard hundreds of kilometers away. It triggered a tsunami in the harbour that tossed ships ashore and drowned those who had survived the initial explosion along the waterfront. The Imo was thrown onto the Dartmouth shoreline.

Perhaps the most widespread source of injury was glass. Windows shattered for miles around, turning into millions of deadly projectiles that blinded, maimed, and killed people who had been watching the fire from what they assumed was a safe distance. In an instant, an estimated 1,950 people were killed, and over 9,000 were injured—many of them severely. Halifax was a city in ruins, shrouded in a black, oily rain from the explosion.

The Blizzard and the Response

As survivors stumbled through the rubble, bleeding and disoriented, fate delivered another cruel blow. The following day, a severe blizzard descended on Halifax, dumping over 40 centimeters (16 inches) of snow on the city. This hampered rescue efforts and brought further misery to the thousands left homeless, who were now struggling to survive in the freezing ruins of their city.

Yet, in the midst of horror, heroes emerged. One of the most celebrated was Vincent Coleman, a railway dispatcher at the Richmond station. As the Mont-Blanc burned, he was about to flee when he remembered an incoming passenger train with hundreds of people aboard was due to arrive. He returned to his telegraph key and tapped out a desperate message: “Hold up the train. Ammunition ship afire in harbour making for Pier 6 and will explode. Guess this will be my last message. Goodbye boys.” Coleman’s message was received, the train was stopped, and hundreds of lives were saved. He was killed at his post when the blast hit.

Aid began to pour in almost immediately from surrounding towns in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. The most significant and immediate assistance, however, came from Boston. Upon hearing of the disaster, the Massachusetts Public Safety Committee organized a relief train packed with doctors, nurses, medical supplies, and food. It battled through the blizzard to arrive in the stricken city, providing critical support. This act of kindness forged a bond that endures to this day. Every year, as a token of gratitude, Nova Scotia sends a massive Christmas tree to the city of Boston, where it is lit as a symbol of remembrance and friendship.

Legacy of the Blast

The Halifax Explosion left an indelible mark on the city and on the world. The rebuilding of Halifax led to improved urban planning and stricter building codes. The sheer number and type of injuries provided a grim but invaluable learning experience for medical professionals, leading to significant advancements in trauma care and pediatric surgery, particularly in the treatment of eye injuries.

The event served as a dark precursor to the destructive power humanity was capable of unleashing, a lesson that would be reinforced with devastating finality at Hiroshima and Nagasaki 28 years later. Today, memorials across Halifax stand as quiet reminders of the day the war came home, a testament to the city that was destroyed and the resilient community that rose from the ashes.