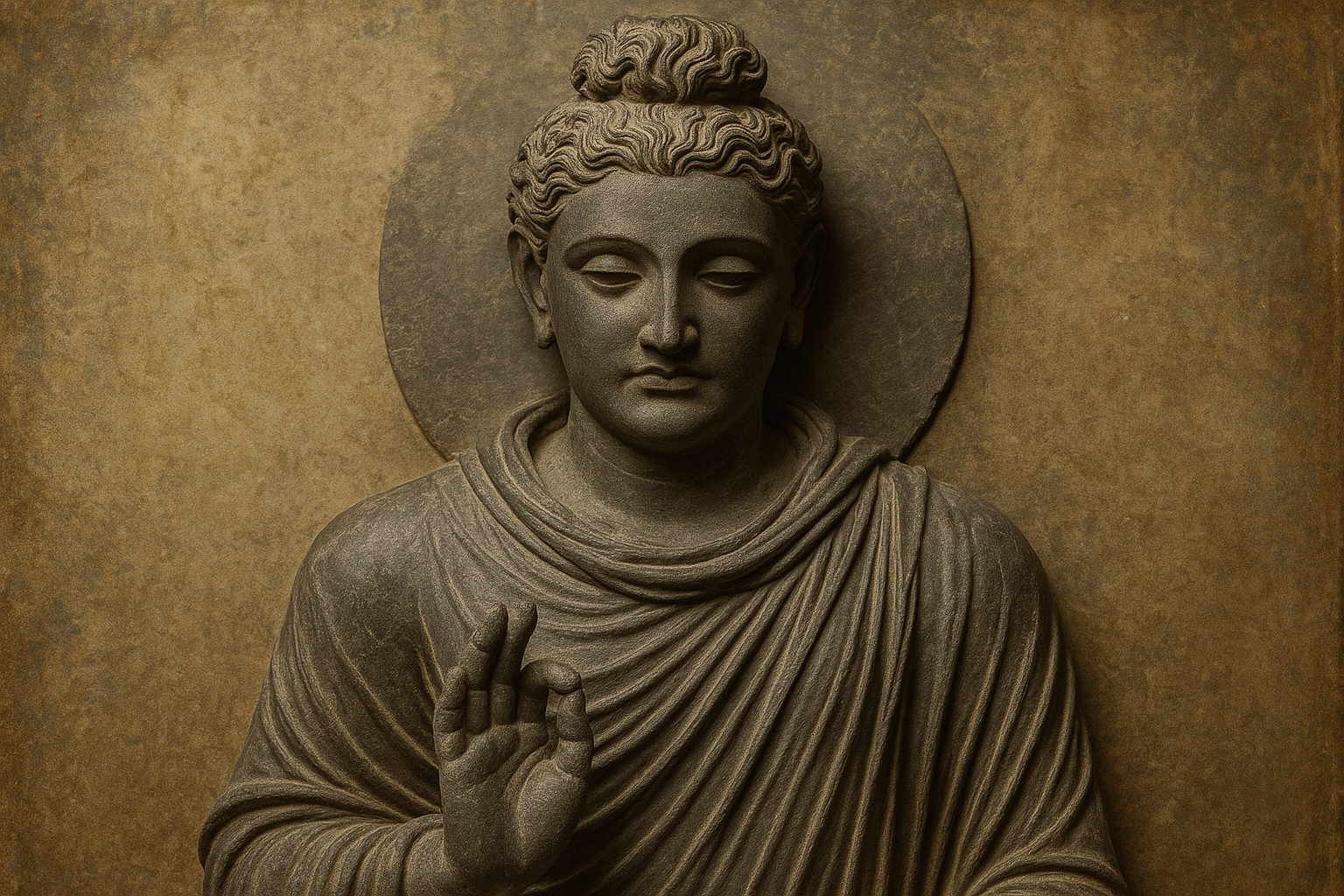

Imagine walking through a museum and stumbling upon a statue. It has the serene, meditative face of the Buddha, but the wavy hair, the strong nose, and the intricately folded robes look like they were carved in a Roman workshop. You are not mistaken. You are looking at a masterpiece from ancient Gandhara, a region where, for centuries, the worlds of the East and West didn’t just meet—they merged into something entirely new and breathtaking.

This is the story of Greco-Buddhist art, a remarkable artistic movement born in the crossroads of civilizations. Located in what is now modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan, the Gandhara region became a melting pot of cultures following the conquests of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BCE.

The Stage is Set: When West Met East

When Alexander’s armies marched through Central Asia, they didn’t just bring military might; they brought Hellenistic culture. After Alexander’s death, his generals established successor states, most notably the Greco-Bactrian and later the Indo-Greek kingdoms. For nearly two centuries, Greek rulers governed parts of Central Asia and Northern India, establishing cities, minting coins with their portraits, and building temples to their gods.

While these kingdoms eventually faded, Hellenistic culture did not. It seeped into the local artistic and architectural traditions. The final, crucial ingredient for this artistic synthesis arrived with the rise of the Kushan Empire (c. 1st-3rd centuries CE). The Kushans, a people of Central Asian origin, controlled a vast territory that included Gandhara and stretched along the lucrative Silk Road. Many Kushan rulers, most famously Kanishka the Great, became devout patrons of Buddhism. It was under their patronage that Gandharan art truly flourished, creating a style that served Buddhist faith with a Hellenistic visual language.

From Symbol to Human Form: A Revolutionary Leap

Before the Gandharan school, Buddhist art was largely aniconic, meaning the Buddha himself was never depicted in human form. Early artists in India represented the Enlightened One through symbols:

- An empty throne symbolizing his royal heritage and spiritual kingship.

- The Bodhi Tree, under which he attained enlightenment.

- A set of footprints, representing his physical presence on earth.

- The Dharma Wheel (Dharmachakra), symbolizing his teachings.

This avoidance of direct representation stemmed from a deep reverence, a belief that the enlightened state of Nirvana was beyond human depiction. The Greek tradition, however, was the complete opposite. From Zeus to Apollo to Aphrodite, the Greeks and their Roman successors were masters of anthropomorphism, believing the ideal human form was the perfect vessel to represent the divine.

It was this Hellenistic comfort with depicting gods as idealized humans that gave Gandharan artists the license to do something revolutionary: create the first human-form images of the Buddha.

Hallmarks of a Hybrid Style: What to Look For

The Greco-Buddhist style is a fascinating blend of features, immediately recognizable once you know what to look for. The artists took the core iconography of Buddhism and rendered it using purely classical techniques.

The “Apollo-like” Buddha

The earliest Gandharan Buddhas are often startlingly Western in appearance. They are portrayed as handsome, serene men with features drawn directly from the Greco-Roman artistic playbook. Key characteristics include:

- Wavy Hair: Instead of the snail-shell curls typical of later Buddhist art, the Gandharan Buddha has flowing, wavy hair gathered into a topknot. This topknot represents the ushnisha, the cranial protuberance symbolizing his expanded wisdom, but it is rendered in the style of a classical chignon or bun.

- Realistic Facial Features: The faces are not stylized but naturalistic, with high-bridged aquiline noses, defined lips, and heavy-lidded eyes, evoking a sense of calm introspection. Many early figures even sport a mustache, a feature that later disappeared from Buddhist iconography.

- Contrapposto Stance: Many standing Buddha figures stand in contrapposto, a classic Greek sculptural pose where the body’s weight is shifted onto one leg, creating a subtle S-curve in the torso. This gives the statues a sense of dynamism and realism, a far cry from the stiff, frontal poses of other ancient art traditions.

Classical Drapery and Form

Gandharan artists were masters of depicting drapery. The Buddha’s monastic robe, the sanghati, is treated like a heavy Greek himation or Roman toga. The fabric clings to the body, revealing the form underneath, with deep, complex, and naturalistic folds cascading down the figure. This realistic treatment of cloth, known as “wet drapery”, was a hallmark of sculptors like Phidias of Athens.

A Supporting Cast of Characters

The synthesis wasn’t limited to the Buddha. Bodhisattvas—enlightened beings who delay their own nirvana to help others—were often depicted as wealthy Indian princes adorned with jewelry and elegant hairstyles, but sculpted with the same Hellenistic realism. Even more striking is the syncretic depiction of protector deities. The Buddha’s fierce protector, Vajrapani, was often depicted as the Greek hero Heracles, complete with his lion-skin and club, standing guard beside the serene Buddha.

More Than Just Statues: Narrative Reliefs

Beyond individual statues, Gandharan artists produced elaborate narrative relief panels that adorned stupas (Buddhist mound-like shrines). These reliefs tell the life story of the Buddha, from his miraculous birth to his Great Departure from the palace, his temptation by the demon Mara, and his first sermon. Here too, the Greco-Roman influence is undeniable. The scenes are filled with figures in dynamic poses, set against architectural backdrops featuring classical Corinthian columns and decorative garlands carried by cherubic figures.

The Legacy of the Gandharan Buddha

The creation of the human Buddha image was a pivotal moment in the history of art. This new, relatable image of the Buddha proved immensely powerful and popular. As monks, merchants, and missionaries traveled the Silk Road, they carried small, portable Gandharan sculptures with them.

This Gandharan prototype became the basis for much of the Buddhist art that followed across Asia. Its influence can be traced in the monumental Buddhas of Bamiyan in Afghanistan (tragically destroyed in 2001), the cave sculptures of Yungang and Longmen in China, and eventually in the artistic traditions of Korea and Japan. While the indigenous Indian school of Mathura developed its own human Buddha image around the same time—with a distinctly different, more robust and spiritualized aesthetic—it was the Greco-Buddhist model that traveled furthest.

The art of Gandhara stands as a powerful testament to the creative power of cultural exchange. It is a beautiful, frozen moment in history when two great civilizations looked at each other and, instead of clashing, chose to create. The result was an art form that gave a human face to the divine and forever changed the visual landscape of one of the world’s great religions.