The Seeds of Division: A Papacy in Avignon

To understand how the Church ended up with multiple popes, we must first look back to the preceding seven decades. Since 1309, the popes had not resided in Rome. Following a bitter conflict between Pope Boniface VIII and King Philip IV of France, a French pope, Clement V, was elected and moved the papal court to Avignon, a city on the Rhône River. This began the era known as the Avignon Papacy, or what the Italian poet Petrarch called the “Babylonian Captivity of the Church.”

For nearly 70 years, a succession of French popes governed from Avignon. While they were not puppets of the French king, they were certainly under his influence. The papal bureaucracy swelled, and its reputation became tainted by accusations of corruption and worldliness. Across Europe, a growing chorus of voices, including prominent figures like St. Catherine of Siena, demanded the papacy return to its historic seat in Rome. In 1377, Pope Gregory XI finally heeded these calls and brought the papal court back to the Eternal City, though he found it a politically volatile and crumbling place. His death just one year later would light the fuse of the schism.

A Mob in Rome and a Hasty Election

In the spring of 1378, the cardinals gathered in Rome to elect Gregory XI’s successor. The atmosphere was electric with tension. The people of Rome, fearing the election of another Frenchman who might return the papacy to Avignon, surrounded the Vatican. Their chants were clear and threatening: “Romano lo volemo, o almeno italiano!” (“We want a Roman, or at least an Italian!”).

Under this intense duress, the cardinals—most of whom were French—hastily elected Bartolomeo Prignano, the Archbishop of Bari, who was an Italian but not a Roman. He took the name Urban VI. Initially, the cardinals seemed to accept their choice. But they soon discovered that they had elected a man with a dangerously volatile and authoritarian personality. Urban VI immediately railed against the cardinals’ luxurious lifestyles, accused them of simony, and threatened to swamp their French majority by creating a flood of new Italian cardinals. He was determined to reform the Church, but his abrasive, tactless, and outright hostile manner alienated the very men who had elected him.

Two Popes, One Church Split in Two

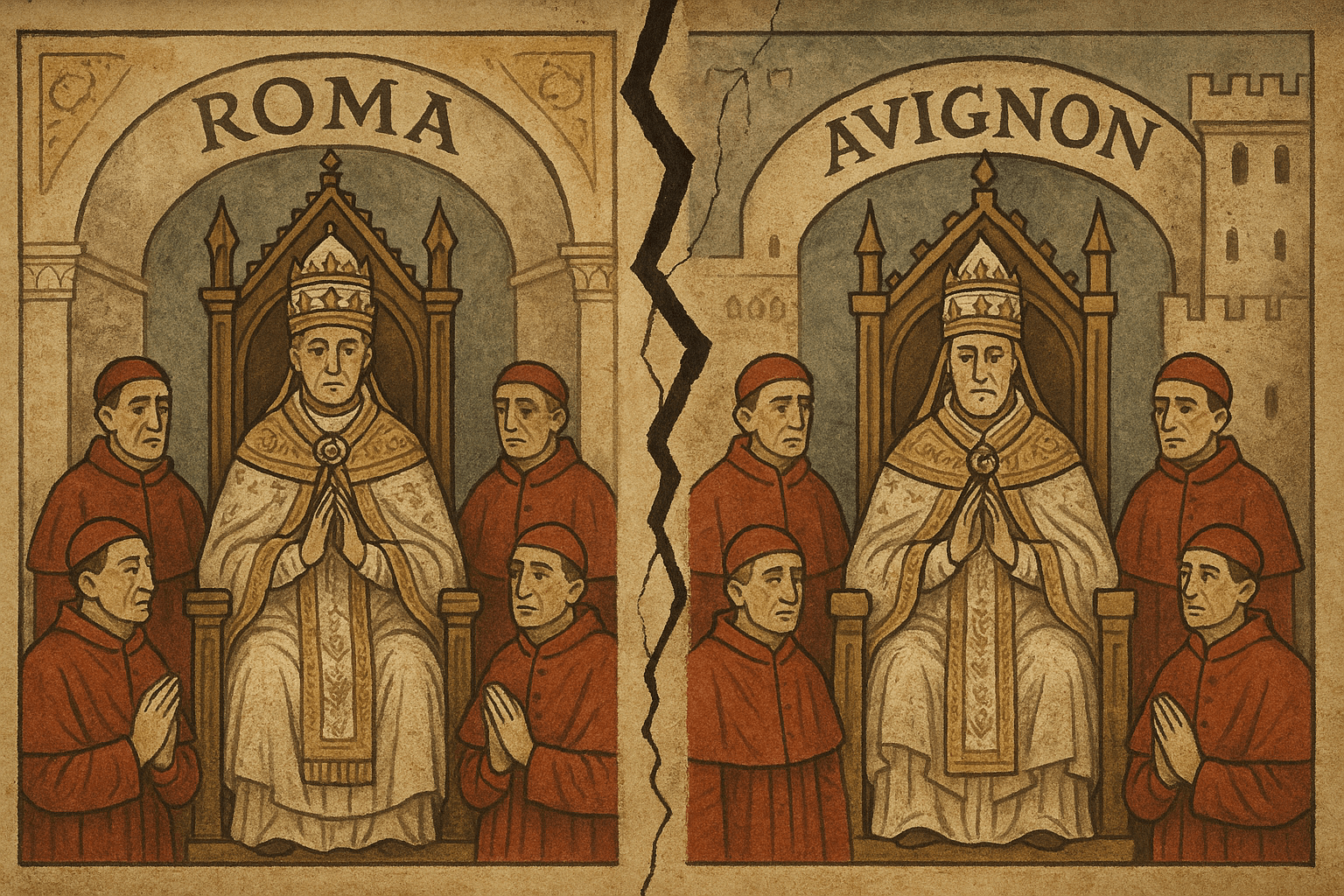

Feeling their power, wealth, and influence threatened—and claiming that the election was invalid because it was conducted under fear of the Roman mob—the French cardinals fled Rome. They regrouped in the city of Anagni and, a few months later, issued a stunning declaration: Urban VI was not the true pope. They declared his election null and void and proceeded to elect one of their own, Cardinal Robert of Geneva, as Pope Clement VII.

When his attempts to take Rome by force failed, Clement VII retreated to Avignon, re-establishing the papal court there. The Western Schism had begun. There were now two popes demanding the obedience of Christendom. Europe was forced to choose sides, and the divisions fell along political lines:

- The Roman Pope (Urban VI): Supported by the Holy Roman Empire, England, Hungary, Poland, and most of Italy.

- The Avignon Pope (Clement VII): Supported by France, Scotland, Naples, Spain, and Sicily.

For nearly four decades, this division persisted. When Urban VI and Clement VII died, their respective colleges of cardinals elected successors, creating two competing papal lines. The schism became institutionalized, a deep wound that refused to heal. Each pope excommunicated the other, creating a terrifying spiritual crisis. Who was the true Vicar of Christ? Whose sacraments were valid? Whose appointees were legitimate? For the average person, it was a question of eternal damnation.

From Bad to Worse: The Council of Pisa

As the scandal dragged on, a new theory gained traction: conciliarism. This was the idea that a general council representing the entire Church held an authority greater than even the pope and could, therefore, act as the ultimate arbiter in the crisis. In 1409, cardinals from both the Roman and Avignonese camps convened the Council of Pisa to end the schism once and for all.

Their solution was bold. They formally deposed both reigning popes—Gregory XII in Rome and Benedict XIII in Avignon—and elected a new, single pope, Alexander V. It seemed like a perfect resolution, but for one major problem: neither of the existing popes recognized the council’s authority to depose them. Both Gregory XII and Benedict XIII refused to abdicate. The Church, in its attempt to solve the two-pope problem, had managed to create a third. The situation had descended from tragedy into farce.

Resolution at a Price: The Council of Constance

The three-pope dilemma finally spurred secular and church leaders to take definitive action. Under the immense pressure and protection of the Holy Roman Emperor, Sigismund, a new and far more authoritative council was called at Constance in 1414.

The Council of Constance, lasting four years, became one of the most important in Church history. It tackled the crisis with methodical determination:

- It convinced the Pisan pope, John XXIII (Alexander V’s successor), to formally convene the council, giving it legitimacy, before he fled and was subsequently captured and deposed.

- It accepted the voluntary resignation of the Roman pope, Gregory XII, who abdicated in the name of Church unity.

- It deposed the stubborn Avignon pope, Benedict XIII, who refused to step down and retreated to a castle in Spain, claiming to be the true pope until his death.

With all three papal seats finally vacant, the council cardinals, joined by representatives from the nations of Europe, elected Oddone Colonna as Pope Martin V in November 1417. This election, accepted by all, officially ended the Great Western Schism.

The Scars of Schism

While the crisis was over, the damage was profound. For nearly 40 years, the papacy had been a source of scandal and division, not unity. The schism severely eroded the pope’s prestige and moral authority. It had demonstrated that the Church could function, and even heal itself, without a supreme papal head, lending powerful support to the conciliar movement.

Most importantly, the Great Schism laid bare the deep-seated political corruption and spiritual decay within the Church’s hierarchy. It fueled a wave of anti-papal sentiment and cries for wholesale reform that the restored papacy struggled to contain. Just a century later, another reformer, Martin Luther, would challenge the authority of Rome. This time, the resulting schism would not be healed.