The Dawn of the Iron Windjammer

By the latter half of the 19th century, the familiar wooden sailing ship was facing an existential threat: the steam engine. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 was a game-changer, offering steamships a dramatic shortcut from Europe to Asia. For the masters of sail, who couldn’t use the canal, survival meant doubling down on their greatest asset: speed over long distances.

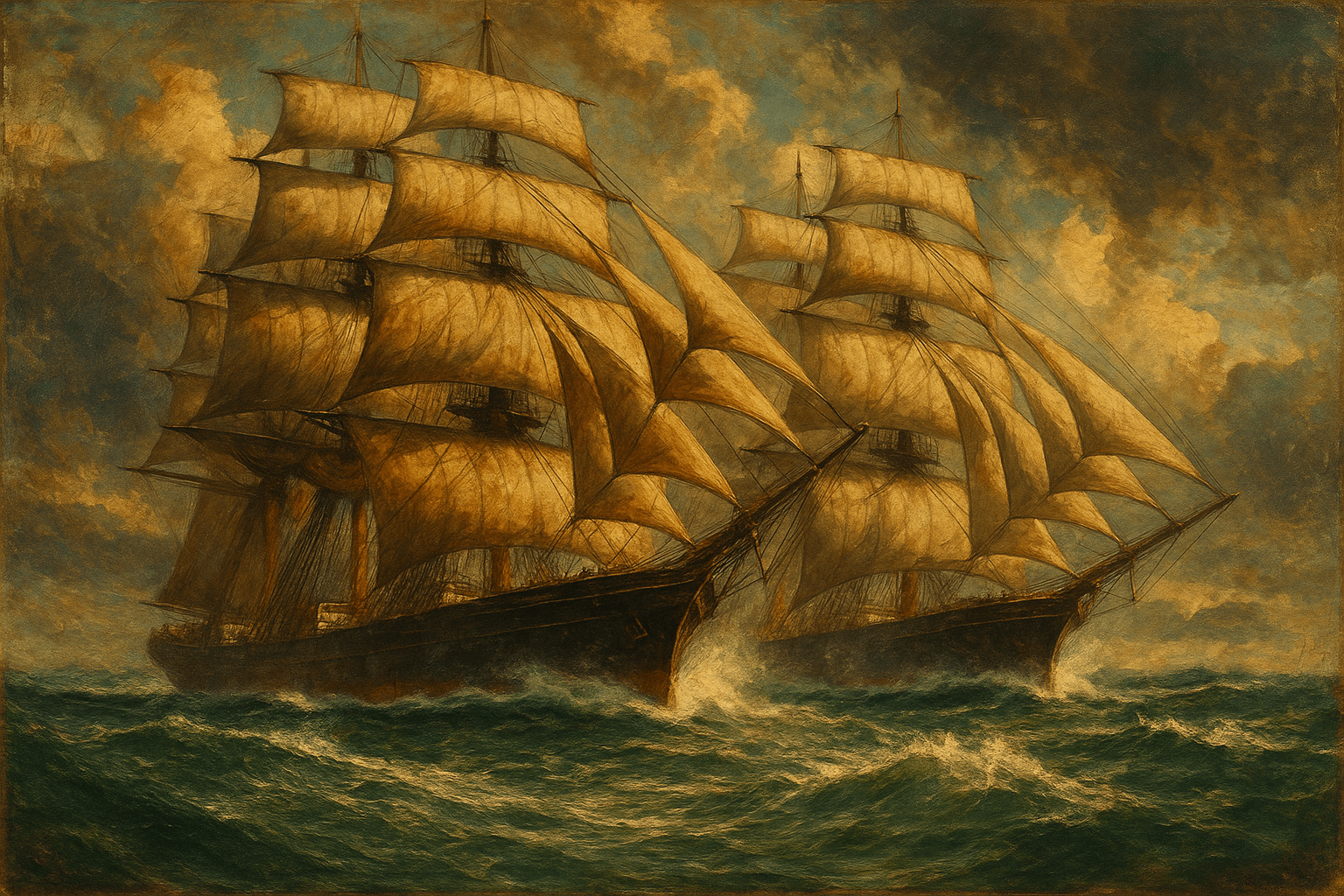

The answer came not from wood, but from iron. While the celebrated tea clippers of the 1860s, like the legendary Cutty Sark, were often of “composite” construction (wooden planks over an iron frame), the true workhorses of this final era were built entirely of iron. These new ships, often called “windjammers”, had several key advantages:

- Strength and Size: Iron hulls could be made longer and narrower without sacrificing structural integrity, allowing for larger ships that could carry more cargo while still slipping through the water at speed.

- Durability: An iron hull was more resistant to the strains of being driven hard in heavy seas. It was less prone to leaking and less susceptible to the marine borers that plagued wooden ships in tropical waters.

- Cargo Capacity: The thinner (yet stronger) iron framing took up less internal space than massive wooden timbers, meaning more room for precious cargo like tea or wool.

These magnificent vessels were the pinnacle of sailing technology, designed to wring every last knot of speed from the winds of the open ocean in a final, glorious defiance of the encroaching machine age.

The Great Tea Race: A Gamble Against Steam

The most famous of the clipper races was the frantic dash from China to London with the first tea crop of the season. The concept was simple: the first ship to unload its cargo at the London docks commanded a premium price. This unofficial “Great Tea Race” created a media frenzy, with newspapers reporting on sightings and betting running rampant.

The race of 1866 remains the most iconic, a nail-biting finish where the clippers Ariel and Taeping docked in London within minutes of each other after a 99-day voyage. However, this race was the zenith for the composite clippers. The Suez Canal gave steamships such an advantage on the China route that, by the 1880s, the tea trade was almost entirely theirs. The iron clippers, while participating, found their reign on this route to be short-lived. A new, even longer racecourse would become their true proving ground.

The Wool Derby: The True Heyday of the Iron Clipper

If the Tea Race was a sprint, the “Wool Derby” from Australia to London was a marathon. This was the trade route where the iron windjammer truly reigned supreme. There was no Suez shortcut; the journey required a perilous, high-speed circumnavigation of the globe, rounding the notoriously stormy Cape Horn.

Dozens of clippers would load wool bales in ports like Sydney and Melbourne, often departing within weeks of each other. Though not an organized event, captains and crews were acutely aware of their rivals. Pride, reputation, and a hefty bonus from the owners were on the line. The journey was a masterclass in meteorology and risk management, as captains charted courses south into the “Roaring Forties”—the strong westerly winds circling Antarctica—to gain a speed advantage, all while dodging icebergs.

This grueling race saw the titans of sail pitted against each other. The old rivals, Cutty Sark and Thermopylae, found a second life in the wool trade. Their 1885 race is the stuff of legend. After 70 days at sea, the two ships sighted each other in the South Atlantic. For a week they battled, often within sight, trading the lead in a spectacular display of seamanship. In the end, Thermopylae reached London just a few hours ahead of her rival.

Ships from the famous “Loch” line, such as the Loch Torridon and Loch Vennachar, were also fearsome competitors. These iron-hulled beauties were built for the punishing conditions of the Southern Ocean and regularly posted voyages of under 80 days—an incredible feat for a vessel powered only by wind.

Life Aboard the Racers

Behind the romance of the clipper races was a reality of relentless toil and ever-present danger. These ships were run by surprisingly small crews to maximize profitability. A vessel over 300 feet long might have fewer than 30 hands, including the captain and his officers.

The captain was the absolute master of his domain, a skilled navigator who had to push his ship to its absolute limit without breaking it. He lived with the constant pressure to “crack on” sail, keeping massive canvases aloft even as gales threatened to tear the masts from the deck. A slow passage could ruin his reputation.

For the crew, life was a cycle of exhaustion and adrenaline. They spent their watches wrestling with frozen, straining canvas high above a churning deck, their fingers raw and their bodies battered. The saying “one hand for the ship, one for yourself” was a literal rule for survival in the rigging. Rounding Cape Horn was the ultimate test, where men battled hurricane-force winds, mountainous waves, and the soul-crushing cold for weeks on end.

The End of an Era

For all their beauty and speed, the iron clippers could not hold back the tide of progress forever. As the 20th century dawned, steam engines became more efficient and reliable, and a global network of coaling stations eliminated the steamship’s primary disadvantage. The opening of the Panama Canal in 1914 was the final nail in the coffin for commercial deep-water sail.

The Great Pacific Iron-Clipper Race faded into history, but its legacy endures. It represents the breathtaking apex of sailing technology and a testament to the skill and bravery of the sailors who drove these iron ships across the world’s oceans. They weren’t just hauling cargo; they were painting a final, spectacular sunset for the entire Age of Sail.