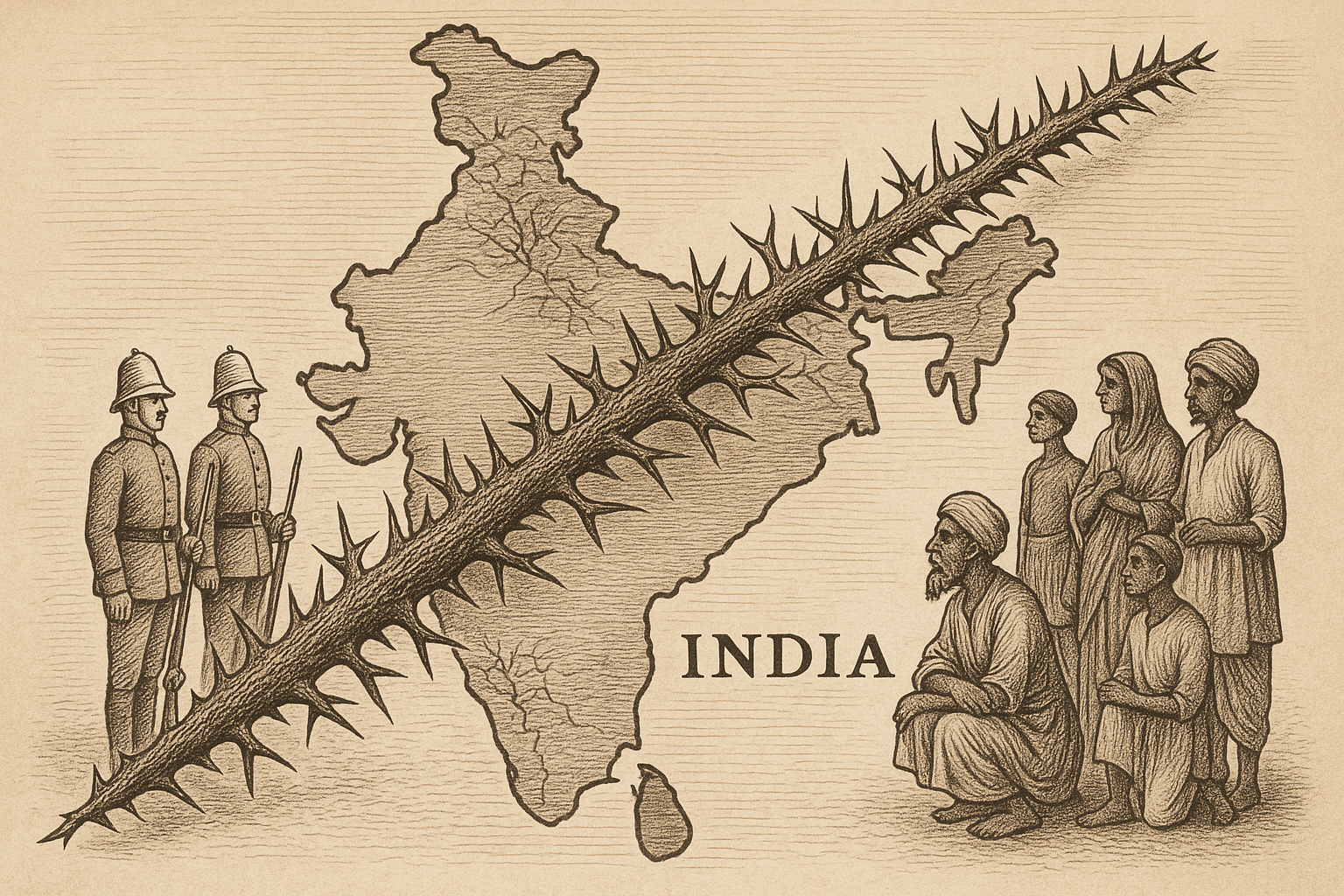

For decades in the 19th century, a colossal, living, breathing hedge sliced across the Indian subcontinent. A thorny rampart of vegetation, it was a monstrous and bizarre instrument of colonial power, designed for one primary purpose: to enforce the British salt tax.

The Roots of the Salt Tax

To understand why anyone would build such a thing, you must first understand the importance of salt. In 19th-century India, salt was far more than a simple seasoning. It was a vital preservative for food in a pre-refrigeration world and an essential nutrient for both humans and livestock. The health of entire communities and their agricultural economies depended on a reliable supply.

The British East India Company, and later the British Raj, saw this necessity not as a public need but as a revenue opportunity. They established a strict monopoly on the production and sale of salt, particularly in the Bengal Presidency. Salt harvested cheaply in other regions—like the Sambhar Salt Lake in Rajputana or along the coast—was deemed “native” salt and posed a threat to the Crown’s profits. To prevent this untaxed salt from being smuggled into their territory, the British established an internal customs line.

Initially, this “Inland Customs Line” was a disjointed series of checkpoints and barriers. But it was porous and inefficient, a constant frustration for the tax collectors. It needed a champion with a vision as grand as it was terrifying.

Constructing a Living Monstrosity

That champion was Allan Octavian Hume, the Commissioner of Inland Customs from 1867 to 1870. (Ironically, Hume would later go on to be a key founder of the Indian National Congress, a pivotal organization in the fight for India’s independence). Hume envisioned a single, unbroken, and “perfectly impassable” barrier. His solution was not brick or stone, but biology.

Under his direction, the existing customs line was consolidated and transformed into a formidable hedge. The scale of the project was mind-boggling:

- Length: At its peak, the hedge ran for at least 1,500 miles (about 2,400 km), starting from the foothills of the Himalayas in Punjab and stretching down to the state of Orissa.

- Materials: It was primarily a living wall, cultivated from hardy, thorny, and drought-resistant species like the Indian Plum, Babool, Karonda, and various cacti. These were planted densely to create a tangled, impenetrable mass.

- Structure: This was no simple garden hedge. It grew to be 10 to 14 feet high and up to 12 feet thick. In places where the plants wouldn’t grow, it was supplemented with great dry-thorn barriers, stone walls, and deep ditches.

A contemporary British official, Sir John Strachey, described it as a structure that “could be compared to nothing else in the world except the Great Wall of China.” Manned by a force of nearly 14,000 customs officers stationed at posts every mile, the hedge was a living, growing, and constantly guarded symbol of colonial control.

Life and Misery Along the Line

The Great Hedge was brutally effective. It choked off the centuries-old smuggling routes, and revenue from the salt tax soared. But its success came at an immense human cost.

For the local population, the hedge was a suffocating presence. It severed ancient pathways, isolating villages from their neighbors and markets. It prevented the free movement of people and, critically, their livestock. Farmers who had for generations led their cattle to natural salt licks found their way blocked by an impassable wall of thorns. Millions of animals weakened and died, crippling local agriculture and contributing to the severity of famines.

The impact on human health was just as devastating. Unable to afford the heavily taxed British salt, the poorest populations suffered from diseases caused by salt deficiency. The hedge became a line of death and desperation, a daily reminder of an oppressive and extractive regime. Smugglers who dared to breach the line faced armed patrols and the constant risk of injury or death, but for many, the potential reward was worth the peril.

The Hedge’s Sudden End

For all its physical might, the hedge was ultimately brought down by a simple policy change. By the late 1870s, many British officials considered the customs line an embarrassing and inefficient monstrosity. In 1879, the government of Viceroy Lord Lytton reformed the entire system.

Instead of trying to physically stop the flow of salt across a 1,500-mile line, they took direct control of the major salt sources, including the Sambhar Salt Lake. By harmonizing the tax rate across different regions, they made the internal customs barrier obsolete. The order was given to abandon the Great Hedge of India.

The end was swift and silent. The thousands of guards were reassigned. Without constant pruning, watering, and reinforcement, nature simply reclaimed its own. The living hedge withered, died, and decayed. Its dead branches were used for firewood, its stone walls were pilfered for local construction, and the earthworks eroded under monsoon rains. Within a generation, this colossal structure had all but vanished from the Indian landscape and, even more remarkably, from public memory.

Rediscovering History’s Forgotten Wall

For over a century, the Great Hedge of India was little more than a historical footnote, mentioned only in obscure administrative reports. Its story was resurrected in the 1990s by a retired British civil servant named Roy Moxham. After stumbling upon a mention of the hedge in an old memoir, he became obsessed with the idea that such a massive project could be so completely forgotten.

Moxham traveled to India and, like a historical detective, followed the old customs line armed with dusty maps and a persistent will. After many false starts, he finally found what he was looking for in the Etawah district of Uttar Pradesh: a small, raised embankment, a few hundred yards long, still marking the old line. It was a faint but tangible trace of the almost-unbelievable reality of the Great Hedge.

Today, the Great Hedge stands as a powerful metaphor. It is a testament to the sheer audacity of colonial engineering and the brutal logic of economic exploitation. Its life and death tell a story of oppression, hardship, and the inevitable decay of empire. And its rediscovery is a thrilling reminder that history is full of lost wonders and forgotten monstrosities, waiting just beneath the surface to be found.