In the middle of the 17th century, Edo—the city we now call Tokyo—was a marvel of the world. As the seat of power for the Tokugawa shogunate, it had exploded in population, becoming one of the largest cities on the planet. Its streets thrummed with the energy of samurai, merchants, artisans, and monks. But this metropolis was built of wood, paper, and bamboo, a sprawling, organic tinderbox waiting for a single, fateful spark.

That spark came on March 2, 1657, the 18th day of the first month in the third year of the Meireki era. What followed was a three-day conflagration of almost unimaginable scale, a disaster that would go down in history as the Great Fire of Meireki. It was an event that not only brought Edo to its knees but also became the crucible in which the modern city was forged.

The Legend of the Cursed Kimono

History is often wrapped in legend, and the story of the Great Fire of Meireki is no exception. The most famous account of its origin, while likely apocryphal, is too compelling to ignore. The tale speaks of a beautiful furisode, a long-sleeved kimono, purchased for a 16-year-old girl. Tragically, she fell ill and died before ever wearing it. Her parents sold it to another family for their daughter, but she too died shortly after. The kimono changed hands a third time, and once again, its young owner passed away.

Believing the garment to be cursed, the families brought it to the Honmyō-ji temple. In accordance with custom, the priest prepared to ritually burn the kimono to free the troubled spirits. As he cast it into the flames, a violent, unexpected gust of wind whipped through the temple courtyard. It caught the burning sleeve, lifting it high into the air and depositing it onto the temple’s wooden roof. The structure, dry from a long winter drought, ignited instantly.

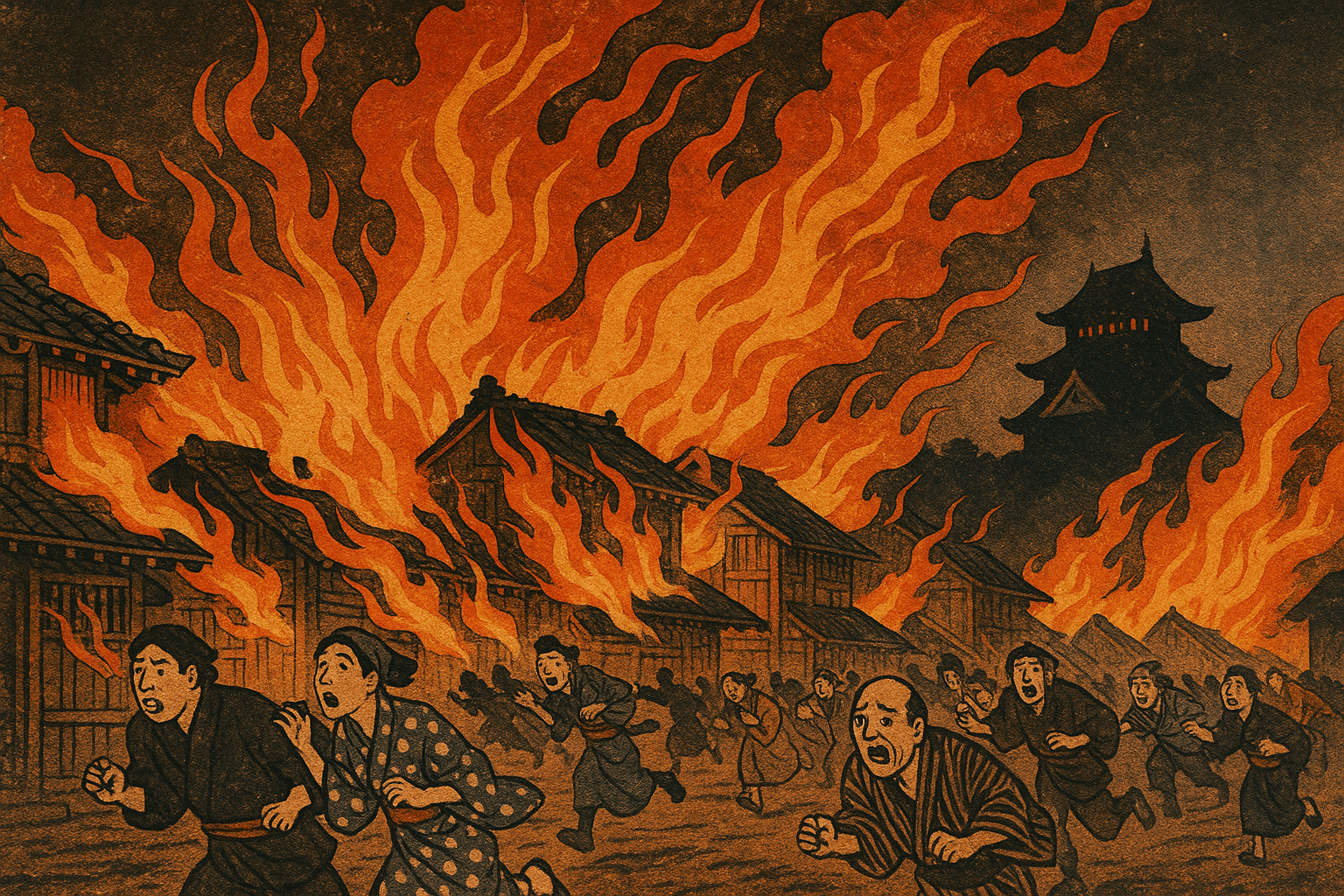

Whether started by a cursed kimono or a more mundane accident, the fire had found the perfect conditions to grow into a monster. A powerful northwesterly gale, a common feature of Edo’s winters, began to fan the flames, pushing a wall of fire south-east across the densely packed city.

An Inferno Across Edo

The city’s design was its undoing. The sankin-kōtai system, which required feudal lords (daimyō) to spend alternate years in the capital, had led to the construction of vast, sprawling wooden estates. These were separated by narrow, winding streets clogged with the timber-and-paper homes of the common townsfolk (chōnin). Official firebreaks were few and far between, and the era’s firefighting brigades, the hikeshi, were ill-equipped to handle a blaze of this magnitude.

For three days, the fire raged with an unrelenting fury:

- Day One: Starting in the Hongō district, the fire swept through the city center, consuming entire neighborhoods of commoners and samurai alike. Panic ensued as residents tried to flee, only to find themselves trapped in a maze of narrow alleyways.

- Day Two: The wind shifted, directing the flames toward the very heart of shogunal power. The blaze leaped across moats and stone ramparts to assault Edo Castle. In a devastating symbolic blow, the castle’s towering main keep (tenshu), the proud emblem of Tokugawa authority, was consumed by the inferno and collapsed in a shower of sparks and embers.

- Day Three: As the wind finally died down and the fire began to run out of fuel, its rampage subsided. What was left was a smoking, desolate landscape of ash and ruin.

The scale of the devastation was staggering. An estimated 60-70% of the city was incinerated. The death toll is believed to have exceeded 100,000 people. Many victims died not from the flames themselves, but from suffocation, stampedes at choked bridges and gates, or by drowning after being pushed into freezing moats and rivers.

Rebuilding from the Ashes

In the aftermath, the Tokugawa shogunate faced a crisis of immense proportions. Hundreds of thousands were homeless, food was scarce, and the government’s own administrative center lay in ruins. However, under the decisive leadership of the regent, Hoshina Masayuki, the shogunate saw not just a disaster, but an unprecedented opportunity to remake the capital.

The rebuilding of Edo was not merely a reconstruction; it was a radical redesign. The government implemented a series of visionary urban planning policies intended to create a safer, more organized, and more governable city. Key changes included:

- Creation of Firebreaks: The most important change was the creation of wide open spaces to act as firebreaks. Main roads were widened, and new, large plazas called hiyokechi (“fire-preventing lands”) and hirokōji (“wide alleys”) were cleared in strategic locations. The area around the Nihonbashi bridge, the city’s commercial center, was cleared to create a massive firebreak.

- Relocation and Reorganization: Many of the great daimyō mansions that had been located near the castle were moved further out, breaking up the dense concentration of flammable structures in the city center. Temples and shrines were similarly relocated to the periphery. The famous Yoshiwara pleasure district was also moved and rebuilt in a more orderly fashion.

- Improved Firefighting: The disaster spurred the creation of a more effective firefighting system. The shogunate established the Jōbikeshi, a permanent, professional force of firefighters stationed at key points around the city.

- Economic Stimulus: The government released massive amounts of gold from its storehouses to fund relief efforts and rebuilding projects. This huge injection of capital created an economic boom, providing work for carpenters, plasterers, and laborers and enriching the merchant class that supplied the materials.

The Legacy of the Great Fire

The Great Fire of Meireki was one of the deadliest urban fires in human history, a tragedy of epic proportions. Yet, its legacy is one of transformation. The disaster forced the Tokugawa shogunate to abandon the chaotic, organic growth of the past and embrace deliberate, rational urban planning.

The Edo that rose from the ashes was a more resilient, spacious, and logical city. The firebreaks and wider streets implemented in 1657 defined the city’s layout for the next two centuries and laid the foundational grid for modern-day Tokyo. The fire solidified the shogunate’s administrative power, demonstrating its ability to manage a crisis and provide for its people. It was a brutal, fiery rebirth, but it created the metropolis that would eventually become one of the world’s great capitals.