To truly understand this dark chapter, we have to move beyond stories and look at the numbers and the forces that drove them. This was a “perfect storm” where climate, politics, religion, and technology converged to create one of history’s most tragic episodes of mass hysteria.

The Ideological Tinderbox: Setting the Stage (c. 1450-1560)

Belief in magic and harmful sorcery (maleficium) was ancient. For centuries, a village-level belief in curses and folk healers was common. What changed in the 15th century was the fusion of this folk belief with an elite, theological concept: the diabolical conspiracy. Suddenly, a witch wasn’t just a spiteful neighbor who soured milk; she was a soldier in Satan’s army, part of a vast plot to overthrow Christendom.

Two key developments ignited this shift:

- Theological Framework: Theologians and inquisitors began writing detailed treatises on the nature of witchcraft. The most infamous of these was the Malleus Maleficarum (“The Hammer of Witches”), published in 1487. It was a terrifyingly detailed, misogynistic guide on how to identify, prosecute, and execute witches.

- The Printing Press: Gutenberg’s invention allowed texts like the Malleus Maleficarum to spread with unprecedented speed. This transformed a localized clerical theory into a continent-wide manual for hysteria, standardizing the “symptoms” of witchcraft and the methods of interrogation.

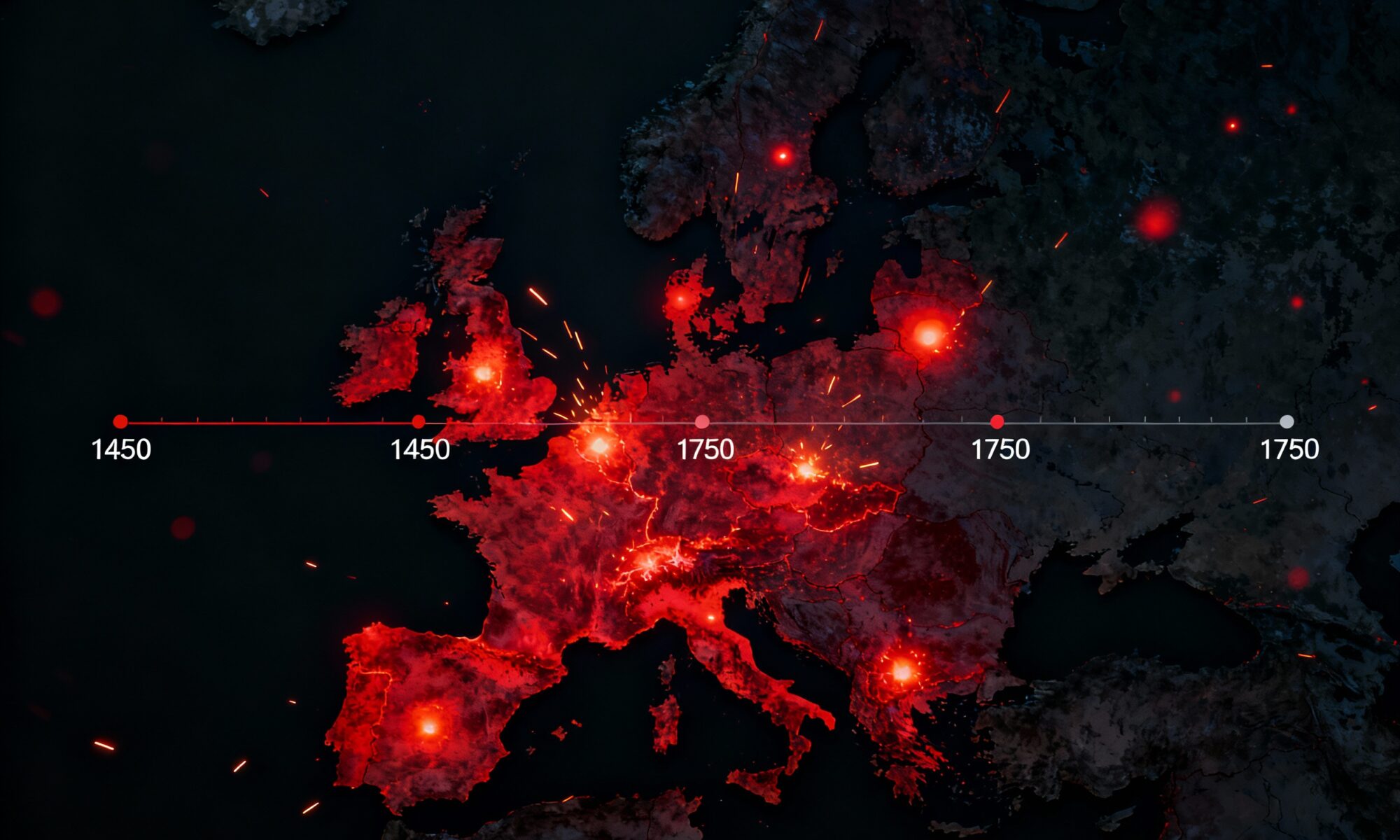

During this initial phase, the trials were sporadic. But the ideological kindling had been laid. The geographic core of the craze also began to emerge: the Holy Roman Empire. This fragmented patchwork of principalities, bishoprics, and free cities, spanning modern-day Germany, Switzerland, and Austria, lacked a strong central legal authority. This meant local panics could ignite and burn out of control without intervention from a higher power.

The Great Hunt: The Peak of the Craze (c. 1560–1660)

If you plot the number of witch trials over time, the century between 1560 and 1660 stands out as a terrifying spike. An estimated 40,000 to 50,000 people were executed for witchcraft in Europe, and the vast majority of these deaths occurred during this 100-year window. This wasn’t a coincidence; it was the result of several overlapping crises.

The Climate Connection: The Little Ice Age

This period of peak witch-hunting coincides almost perfectly with the most severe phase of the “Little Ice Age”, a period of global cooling. The “Grindelwald Fluctuation” brought brutally cold winters, cool and wet summers, and devastating climatic volatility.

For an agrarian society, this was catastrophic. It led to:

- Repeated crop failures and famine.

- Starvation of livestock.

- Increased disease in both humans and animals.

- Unusually powerful storms and floods.

When faced with inexplicable and repeated misfortune, people sought an explanation. The diabolical witchcraft theory provided a convenient one. Why did the crops fail for the third year in a row? A witch must have summoned a hailstorm. Why did the cows stop giving milk? A curse. The witch became the scapegoat for a world thrown into chaos by climate change.

The Political and Religious Cauldron

Climate was the stressor, but religion and politics provided the mechanism for the violence. The Protestant Reformation had fractured Christendom. The century from 1560 onward was defined by intense religious conflict between Catholics and Protestants.

Both sides used witch-hunting as a tool. In a process known as “confessionalization”, rulers sought to forge godly societies and prove their piety. Cracking down on Satan’s supposed agents was a very public way to do so. Protestant and Catholic territories competed to show who was more zealous in purifying their land of evil, leading to a grim “race to the bottom.”

The Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648), a brutal conflict that ravaged the Holy Roman Empire, was the ultimate accelerator. The war brought immense social breakdown, death, and paranoia. It’s no surprise that some of the most horrific witch-hunts on record occurred in its shadow. In the territories of Würzburg and Bamberg, the prince-bishops launched systematic extermination campaigns, executing hundreds in just a few years, targeting not just the poor and elderly, but even elites and children in their spiraling paranoia.

The Anatomy of a Panic

A typical large-scale hunt started small. An accusation, often born of a personal dispute or linked to a climatic disaster, would lead to an arrest. The key to the chain-reaction hunts that defined the peak years was torture. Under extreme duress, the accused would not only confess to impossible crimes—flying on broomsticks, attending demonic Sabbats, desecrating the host—but they would be forced to name accomplices. Each new name created a new victim, and the panic would spiral outward, consuming entire villages.

The victims were overwhelmingly women (around 75-80%), often those on the margins of society: the elderly, the poor, widows, and healers. Misogyny was baked into the very fabric of witchcraft theory; women were seen as morally weaker and more susceptible to the Devil’s temptations.

The Waning of the Flames (Post-1660)

Just as a combination of factors lit the pyres, a new combination extinguished them. The decline of the great hunts was gradual but steady after the mid-17th century.

- Legal and Judicial Reform: Centralizing states, like France under Louis XIV, began to assert greater control over local courts. They sent appeals judges who were skeptical of the chaos and often overturned local verdicts. Procedural rules were tightened, and the use of torture was increasingly restricted.

- The Rise of the Enlightenment: A new intellectual current was gaining momentum. The scientific revolution offered natural explanations for events previously blamed on the supernatural. Elites, judges, and theologians grew deeply skeptical of confessions obtained under torture and the very idea of a diabolical pact.

- End of the Religious Wars: The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 ended the Thirty Years’ War and gradually lowered the religious temperature across Europe. With less pressure to prove religious purity through violence, a key motivation for the hunts faded.

By the 18th century, the great hunts were largely over. The last official execution for witchcraft in the Holy Roman Empire was in 1775, and in Switzerland in 1782. The fire of the craze had finally burned itself out.

The Great European Witch-Hunt reminds us that societal panics are not born from a single cause. They emerge when social, political, and even environmental anxieties fester and are channeled against a vilified “other.” It was a product of a specific time—an early modern world grappling with climate shock, religious revolution, and state formation—and serves as a chilling lesson on the hunt for scapegoats in times of crisis.