Setting the Scene: A Land of Promise and Hardship

To understand how soldiers ended up fighting birds, we must look at the Australia of the early 1930s. The world was gripped by the Great Depression, and Australia was hit hard. In the years following World War I, the government had established soldier settlement schemes, granting tracts of land to returning veterans, many in the marginal wheatbelt region of Western Australia. These men, who had faced the horrors of Gallipoli and the Western Front, were now trying to forge a new life as farmers.

Their task was anything but easy. The land was difficult, and a severe drought was crippling their efforts. But as if economic depression and tough agricultural conditions weren’t enough, a new enemy was advancing on their fields. This enemy was not a foreign army, but a native one.

The Feathered Invasion

Following their breeding season, an estimated 20,000 emus began their annual migration, moving from the inland regions towards the coast. Ordinarily, this was a natural phenomenon. In 1932, however, the newly established farms in the Campion and Walgoolan districts presented an irresistible detour. The freshly cleared land and abundant water for livestock were an oasis for the migrating birds.

The emu army descended upon the farmlands with devastating effect. They devoured and trampled wheat crops, but their most destructive act was their blatant disregard for fences. The large, powerful birds smashed through the farmers’ carefully constructed rabbit-proof fences, creating huge gaps that allowed hordes of rabbits and other pests to follow in their wake, causing even more damage. The farmers were desperate. A delegation of ex-soldiers, using their military background, appealed to the Minister of Defence, Sir George Pearce, for a military solution.

A Military Solution for a Pest Problem

The request seemed absurd, but the government agreed. The decision was driven by a few key factors:

- Public Relations: It was seen as a way to show tangible support for the struggling WWI veterans.

- Military Training: The army viewed it as a perfect opportunity for live-fire machine gun practice.

- Cost: The farmers themselves agreed to pay for the ammunition, housing, and food for the soldiers.

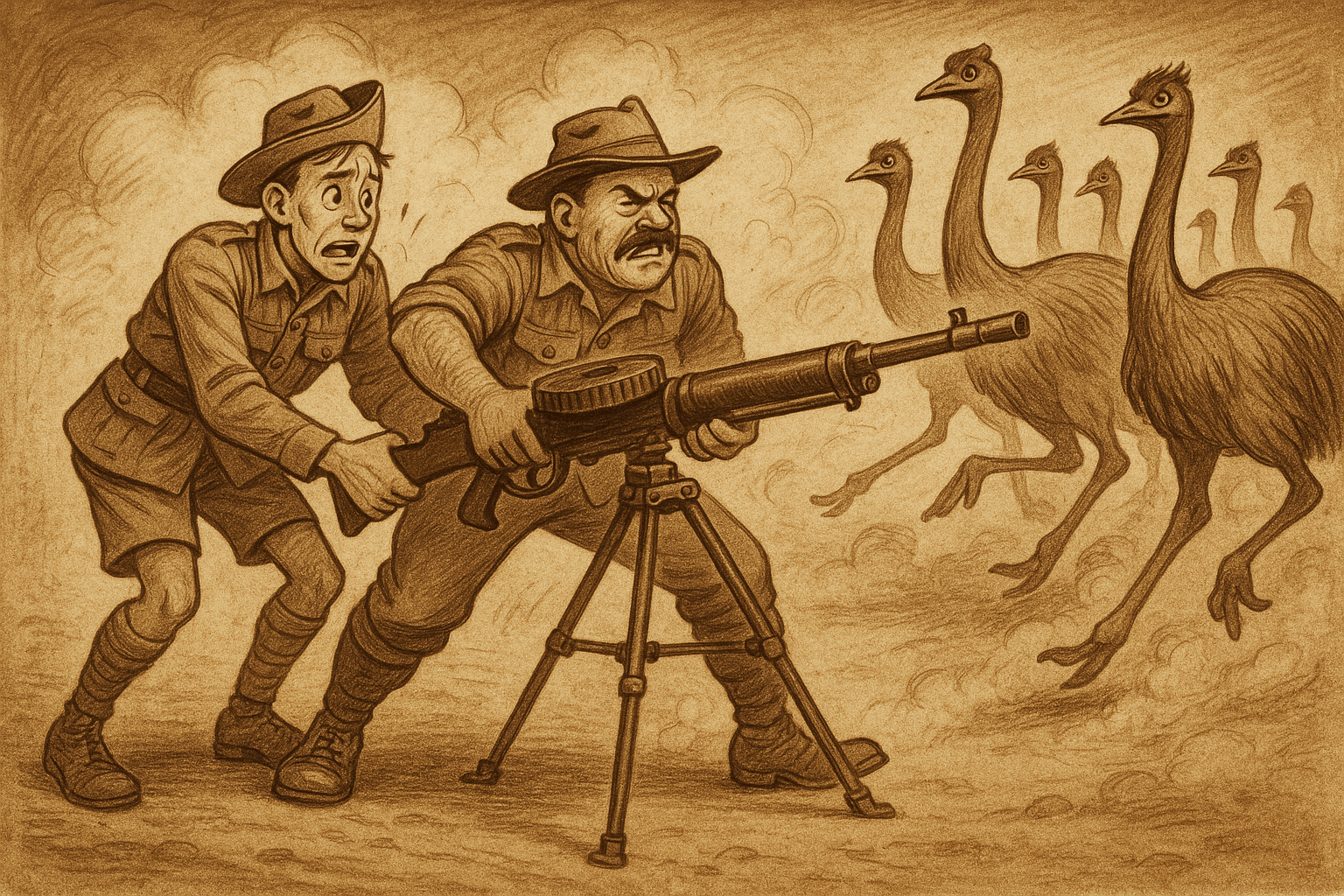

So, in October 1932, Major G.P.W. Meredith of the Seventh Heavy Battery of the Royal Australian Artillery was dispatched to the front line. He was accompanied by Sergeant S. McMurray and Gunner J. O’Halloran, and their arsenal consisted of two Lewis automatic machine guns and 10,000 rounds of ammunition. To capture the expected triumph for the newsreels, a Fox Movietone cinematographer came along for the ride.

The First Engagement: The Emus Strike Back

On November 2, the “war” began. The soldiers encountered a flock of about 50 emus. This, they thought, would be an easy start. The gunners set up and took aim. But the emus were not the stationary targets the military had hoped for. Upon the first shots, the flock didn’t panic and flee as a mob. Instead, they scattered, splitting into smaller groups and running in erratic, unpredictable patterns.

The heavy Lewis guns, designed to mow down lines of advancing infantry, were ill-suited for hitting fast, weaving targets. After firing a torrent of bullets, the soldiers had managed to kill only a handful of birds. The rest had vanished into the bush. Major Meredith was stunned by their tactics. In his official report, he noted their surprising resilience and guerilla-like strategy:

“If we had a military division with the bullet-carrying capacity of these birds it would face any army in the world… They can face machine guns with the invulnerability of tanks.”

A few days later, the soldiers planned a more elaborate ambush near a local dam where over 1,000 emus had been spotted. This time, they would wait for the birds to be in point-blank range. As they opened fire, however, the lead gun jammed after firing just twelve rounds. Before the second gun could be brought to bear, the thousand-strong emu force had melted away, leaving fewer than a dozen of their comrades behind.

Humiliation on Wheels and a Tactical Retreat

The campaign’s most comically disastrous moment came when the military attempted to mount one of the Lewis guns on a truck. The plan was to chase the emus down. The reality was a farce. The truck was too slow to keep up with the sprinting birds, and the ride was so bumpy that the terrified gunner couldn’t land a single shot. In one infamous incident, an emu running alongside the truck became so entangled with the vehicle that it swerved and crashed through a farmer’s fence, causing yet more property damage without a single emu casualty.

After nearly a week of intense “combat”, thousands of rounds had been spent, and the official body count was a pathetic 98 emus. On November 8, Major Meredith and his men were recalled. The press had a field day, with headlines gleefully reporting the military’s defeat. One ornithologist famously quipped that the emus had “won every round.” The Great Emu War had become a national joke.

Round Two and the Bitter End

Despite the public humiliation, the farmers’ problems hadn’t gone away. The emus, emboldened by their victory, continued their rampage. Under intense political pressure, the military was sent back in for a second attempt on November 13.

This time, Meredith’s unit was slightly more successful. Having learned from their previous failures, they engaged smaller groups and had better luck. Over the next month, they fired 9,860 rounds to kill a reported 986 emus—an average of exactly 10 bullets per kill. While an improvement, it was hardly an efficient culling operation, and many more birds were wounded and escaped. On December 10, the operation was officially ceased. Meredith himself acknowledged that a huge number of emus remained, and the core problem was unsolved.

Legacy of the Emu War

The Great Emu War stands as a testament to human hubris and the folly of applying brute force to a problem that requires a more nuanced solution. The military intervention was a costly and embarrassing failure. In the years that followed, the government turned to a far more effective method: a bounty system that encouraged private hunters to cull the birds. This, combined with the construction of stronger, more effective emu-proof barrier fences, eventually brought the problem under control.

Today, the story serves as one of history’s most absurd footnotes—a reminder that sometimes, the most sophisticated weapons are no match for a determined, fast-running, and surprisingly clever native animal. The emus didn’t have generals or battle plans, but by simply being themselves, they defeated a modern army and secured their place in military history.