A Thirst for Fur and Power

By the early 1600s, the European beaver had been hunted to near extinction. Fashion, however, was a powerful force. The high-status felt hat, made from the beaver’s soft under-pelt, was a must-have accessory for any gentleman of means. To meet this demand, European powers turned their eyes to the seemingly limitless wilderness of North America.

Two major colonial powers established the trade networks that would define the conflict:

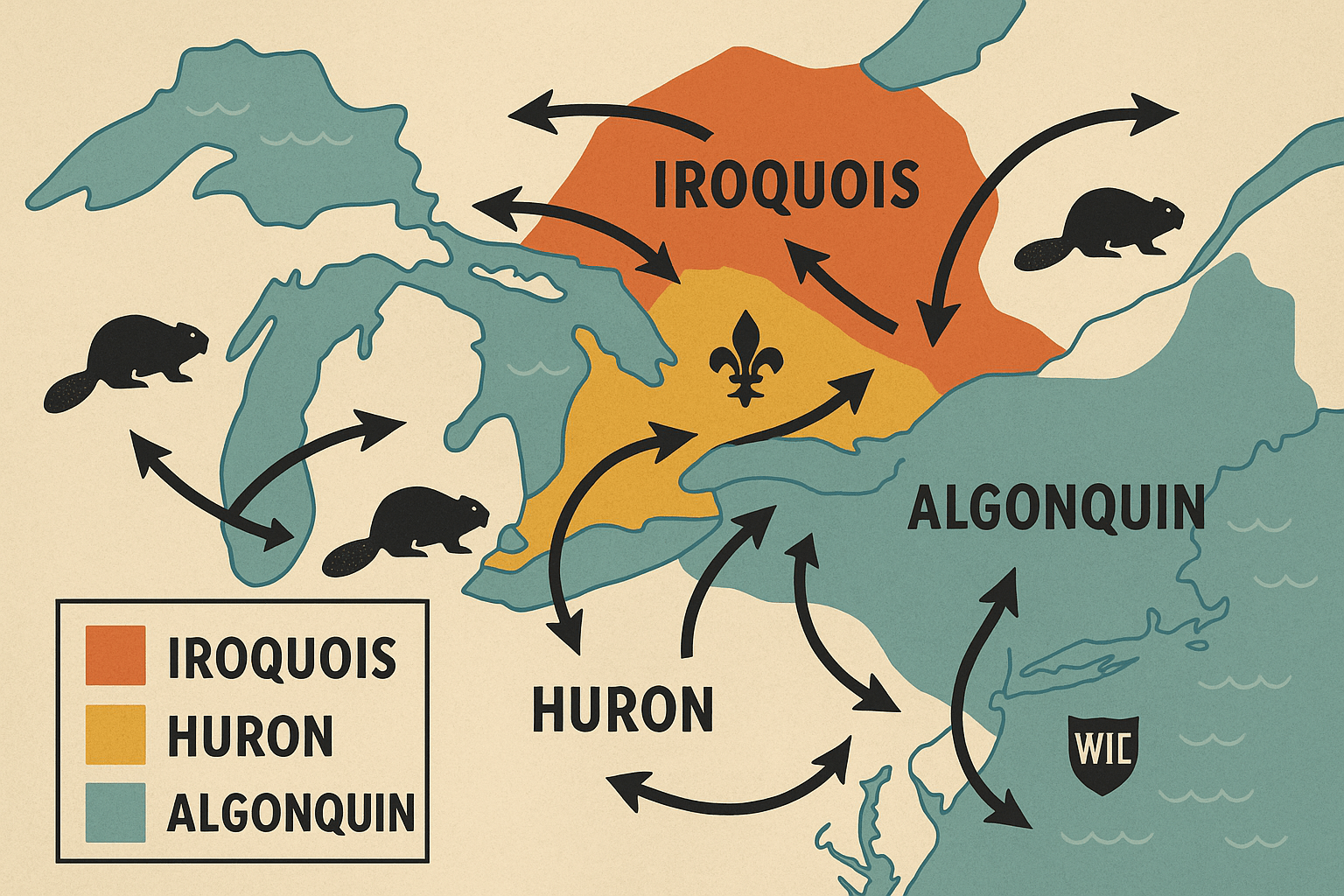

- The French: Based in Quebec and Montreal, they forged deep alliances with the Algonquin-speaking peoples of the Ottawa Valley and, most importantly, the powerful Huron-Wendat Confederacy. The Huron-Wendat controlled a vast trading network that stretched from the St. Lawrence River deep into the Great Lakes, funneling a massive supply of furs to their French partners.

- The Dutch: Centered at Fort Orange (present-day Albany, New York), the Dutch allied themselves with the formidable Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois Confederacy.

For Indigenous peoples, this new trade was revolutionary. In exchange for furs, they received European goods that changed their way of life: iron kettles, axes, cloth, and, most consequentially, firearms. Access to these goods, especially guns, provided a decisive military and economic advantage over rival nations. Suddenly, traditional rivalries were amplified by an arms race, with the fur trade as its engine.

The Rise of the Iroquois Confederacy

The Iroquois Confederacy—a sophisticated political alliance of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca nations—found itself in a precarious position. Located in what is now upstate New York, their territory, known as Iroquoia, was quickly depleted of beavers by the 1630s. Their access to vital European goods was threatened. Cut off from the prime fur-trapping lands to the north and west by the French-allied Huron-Wendat, the Iroquois faced a choice: fade into obscurity or seize control of the trade by force.

They chose force. Bolstered by their strategic alliance with the Dutch, who readily supplied them with guns to undermine the French, the Iroquois embarked on a campaign of terrifying scope and efficiency. Their goal was twofold: to raid their neighbors for their stocks of pelts and to hijack the existing trade routes, redirecting the flow of furs from the French at Montreal to themselves and their Dutch partners at Fort Orange.

A Campaign of “Mourning Wars” and Conquest

The Iroquois campaigns were more than just economic raids; they were intertwined with the cultural practice of the “Mourning War.” Devastated by European diseases to which they had no immunity and by ongoing skirmishes, Iroquois communities needed to replenish their populations. Warriors were sent out not only to seek revenge but also to take captives. These captives were often adopted into Iroquois families to replace the dead, becoming full members of the Confederacy. This practice gave the Iroquois a unique ability to absorb their enemies and maintain their strength even through decades of conflict.

Beginning in the 1640s, the Iroquois unleashed a series of devastating attacks. Their primary target was the Huron-Wendat Confederacy, the linchpin of the French fur empire. Iroquois war parties, armed with Dutch muskets, moved with deadly speed. They ambushed Huron-Wendat canoe flotillas, attacked hunting parties, and laid siege to their fortified villages.

The climax came in 1649. In a shocking campaign, the Iroquois overran and destroyed the core of the Huron-Wendat homeland. Villages were burned, and their inhabitants were killed or taken captive in massive numbers. The Jesuit missionaries living among them were martyred, and the once-mighty Huron-Wendat Confederacy was shattered, its survivors fleeing west to seek refuge among other Algonquin peoples.

With their main rival eliminated, the Iroquois didn’t stop. Throughout the 1650s, they systematically attacked and dispersed other nations that stood in their way, including the Petun, the Neutral Nation, and the Erie people. Their sphere of influence expanded dramatically, pushing displaced Algonquin refugees westward and creating a vast, depopulated “beaver hunting ground” that they alone controlled.

Changing Tides and the Great Peace

The French were stunned and largely powerless in the face of the Iroquois onslaught. Their allies were scattered, their fur trade was in ruins, and the colony of New France itself was threatened. The situation only began to change in the 1660s when King Louis XIV of France dispatched a regiment of professional soldiers, the Carignan-Salières, to North America. These troops marched directly into Iroquoia, burning villages and food stores. While they failed to crush the Iroquois, they demonstrated that the French could now match them militarily.

The wars continued to ebb and flow for another three decades. When the English conquered New Netherland in 1664, they took over the Dutch role, maintaining the alliance with the Iroquois through a pact known as the Covenant Chain. The Iroquois were now a crucial buffer and proxy for the English against the French.

By the turn of the 18th century, however, all sides were exhausted. The Iroquois had suffered heavy losses, and their power, while still immense, was being checked by a resurgent New France and its western Native allies. This exhaustion paved the way for a remarkable diplomatic achievement. In 1701, representatives from nearly 40 Indigenous nations, the Iroquois, and the French gathered in Montreal. The result was the Great Peace of Montreal, a treaty that ended the Beaver Wars. The Iroquois agreed to stop their attacks and remain neutral in future wars between England and France, a promise they largely kept for over 50 years.

The Enduring Legacy of the Beaver Wars

The century of conflict left an indelible mark on North America.

- Ecological Devastation: The relentless pursuit of beaver pelts led to the animal’s functional extinction across much of the Eastern Woodlands. This had a cascading ecological impact, as beaver dams, which create rich wetland habitats, vanished from the landscape.

- Demographic Upheaval: The political map of Indigenous North America was completely redrawn. Entire confederacies like the Huron-Wendat were destroyed, while new, multi-ethnic communities (like the Wyandot) formed from the refugee remnants. Vast regions of the Ohio Valley were depopulated, only to be resettled later by other groups.

- Political Transformation: The Beaver Wars established the Iroquois Confederacy as the dominant Indigenous power in the Northeast, a position of influence they would leverage brilliantly between the rival English and French empires for decades. The conflict set the stage for the larger imperial struggles of the 18th century, ultimately leading to the French and Indian War.

The Great Beaver Wars were a brutal chapter in North American history, a complex collision of commerce, culture, and conquest. They serve as a powerful reminder that before the arrival of European settlers in large numbers, the continent was already a dynamic and contested space, where Indigenous nations vied for power in ways that shaped the future for everyone.