The Arrival of an Exotic Treasure

The story doesn’t begin in the manicured fields of Holland, but in the mountain steppes of Central Asia. Tulips were first cultivated and celebrated in the Ottoman Empire, where they were a symbol of power and wealth, adorning the gardens of sultans. It wasn’t until the late 16th century that these vibrant flowers made their way to the Netherlands, largely thanks to botanist Carolus Clusius, who planted a small collection at the University of Leiden’s botanical garden.

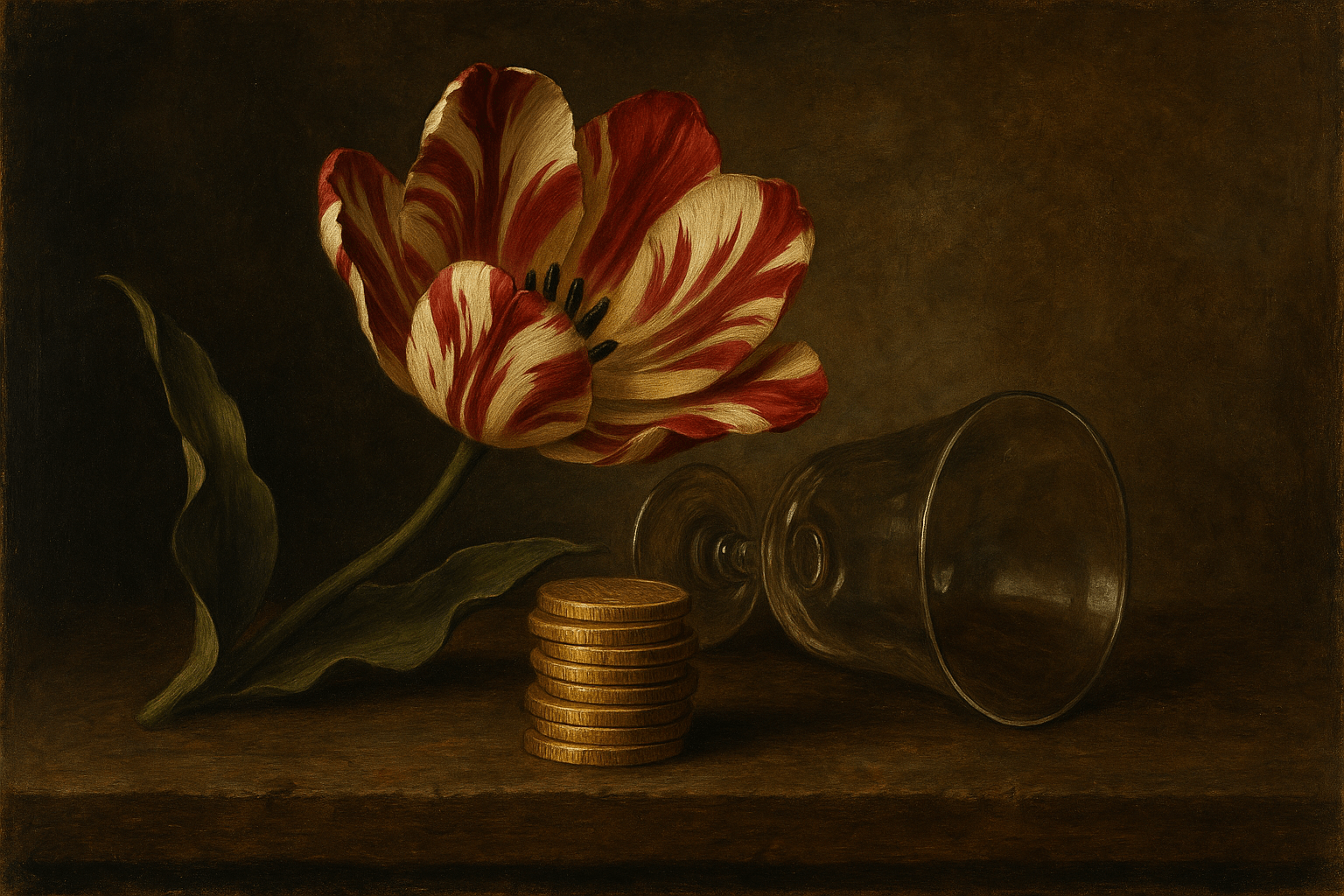

In a nation flush with cash from its burgeoning global trade empire, the unique and exotic tulip quickly became the ultimate status symbol. Its intense colors were unlike anything seen in native European flora. Wealthy merchants and nobles clamored to display rare varieties in their gardens, a visible testament to their taste and fortune. The most coveted of all were the “broken” tulips—bulbs infected with a non-lethal mosaic virus that caused their petals to break into stunning, flame-like patterns of multiple colors. These patterns were unpredictable and unique to each bulb, making them living works of art. The rarest and most beautiful of these, like the legendary Semper Augustus with its white and crimson flames, became the crown jewels of the horticultural world.

From Hobby to “Windhandel”

Initially, tulip trading was a pastime for wealthy connoisseurs and dedicated growers. But as demand soared, the prices began to climb. By the 1630s, the market had morphed from a simple trade in physical bulbs to a full-blown speculative frenzy. Because tulip bulbs can only be uprooted and moved during their dormant phase in the summer, traders in the winter months began trading promissory notes for bulbs that were still in the ground. This futures market, known as windhandel or “wind trade”, allowed for rapid-fire speculation without any physical asset changing hands.

Taverns and pubs across Dutch cities transformed into makeshift stock exchanges. People from every walk of life—merchants and artisans, sailors and servants—were swept up in the craze. They sold property, liquidated inheritances, and took out massive loans to get in on the action. The belief that prices could only go up was infectious. Why work for a modest wage when you could make a fortune in a matter of weeks trading flower bulbs?

The valuations became utterly divorced from reality. A single bulb of a variety called Viceroy was famously recorded as being exchanged for a basket of goods worth a small fortune:

- Two lasts of wheat

- Four lasts of rye

- Four fat oxen

- Eight fat swine

- Twelve fat sheep

- Two hogsheads of wine

- Four tuns of beer

- Two tons of butter

- 1,000 pounds of cheese

- A complete bed

- A suit of clothes

- A silver drinking cup

By the winter of 1636-1637, the market reached its zenith. Prices for some common bulbs increased twenty-fold in a single month. A single rare Semper Augustus bulb was said to be worth around 5,500 guilders—more than the price of a luxurious house on the Amsterdam canals and over 15 times the annual salary of a master craftsman.

The Great Crash of February 1637

Like all speculative bubbles, this one was destined to pop. The end came swiftly and without mercy. On February 3, 1637, at a routine bulb auction in the city of Haarlem, a buyer failed to show up and pay for a purchase of high-value bulbs. The news of this default spread like wildfire, and the delicate psychology of the market shattered in an instant.

Confidence evaporated. What was once seen as a can’t-lose investment was suddenly revealed to be a gamble on a simple flower. Panic set in. Everyone rushed to sell, but there were no buyers to be found. Prices plummeted by 90%, then 95%, then over 99% within weeks. Fortunes built on paper profits were wiped out overnight. People who had taken out loans to buy bulbs at inflated prices were left with worthless plants and crippling debt. Those who had sold their homes and businesses were ruined. The “wind trade” contracts became a source of bitter dispute, as buyers refused to honor their agreements to pay exorbitant sums for bulbs that were now practically worthless.

The Aftermath and Historical Re-evaluation

The social fallout was significant. Bankruptcies mounted, and the courts were flooded with lawsuits between defaulting buyers and furious sellers. The Dutch government attempted to intervene, offering to convert contracts into options with a small penalty, but the damage was done. For many, Tulip Mania became a powerful moral lesson—a story of greed, folly, and the ruin that follows when a society loses its collective mind.

For centuries, the story of Tulip Mania was told as a cautionary tale of mass hysteria, most famously chronicled in Charles Mackay’s 1841 book, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. This narrative painted a picture of a nation driven to economic ruin by a flower.

However, modern historians like Anne Goldgar have offered a more nuanced perspective. In her book Tulipmania, she argues that the craze, while real, was not as widespread as the popular story suggests. The speculation was largely confined to a network of wealthy merchants and skilled artisans, not the entire populace. Furthermore, she contends that the economic impact on the Dutch Republic as a whole was quite limited, and the stories of total ruin were often exaggerated by Calvinist moralists of the time who sought to condemn the earthly sin of speculation.

A Timeless Lesson

Whether a national catastrophe or a more limited mania, the Dutch Tulip Bubble remains a powerful and enduring allegory. It serves as a textbook example of a speculative bubble, where the price of an asset decouples from its intrinsic value and is instead driven by greed and the “greater fool” theory—the belief that you can always sell it to someone else for a higher price.

From the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s to the housing market crash of 2008 and the volatile swings of cryptocurrency, the echoes of Tulip Mania can be heard across centuries. It stands as a stark reminder that human psychology, herd mentality, and the intoxicating dream of getting rich quick are forces as powerful and timeless as history itself.