A World of Clashing Swords

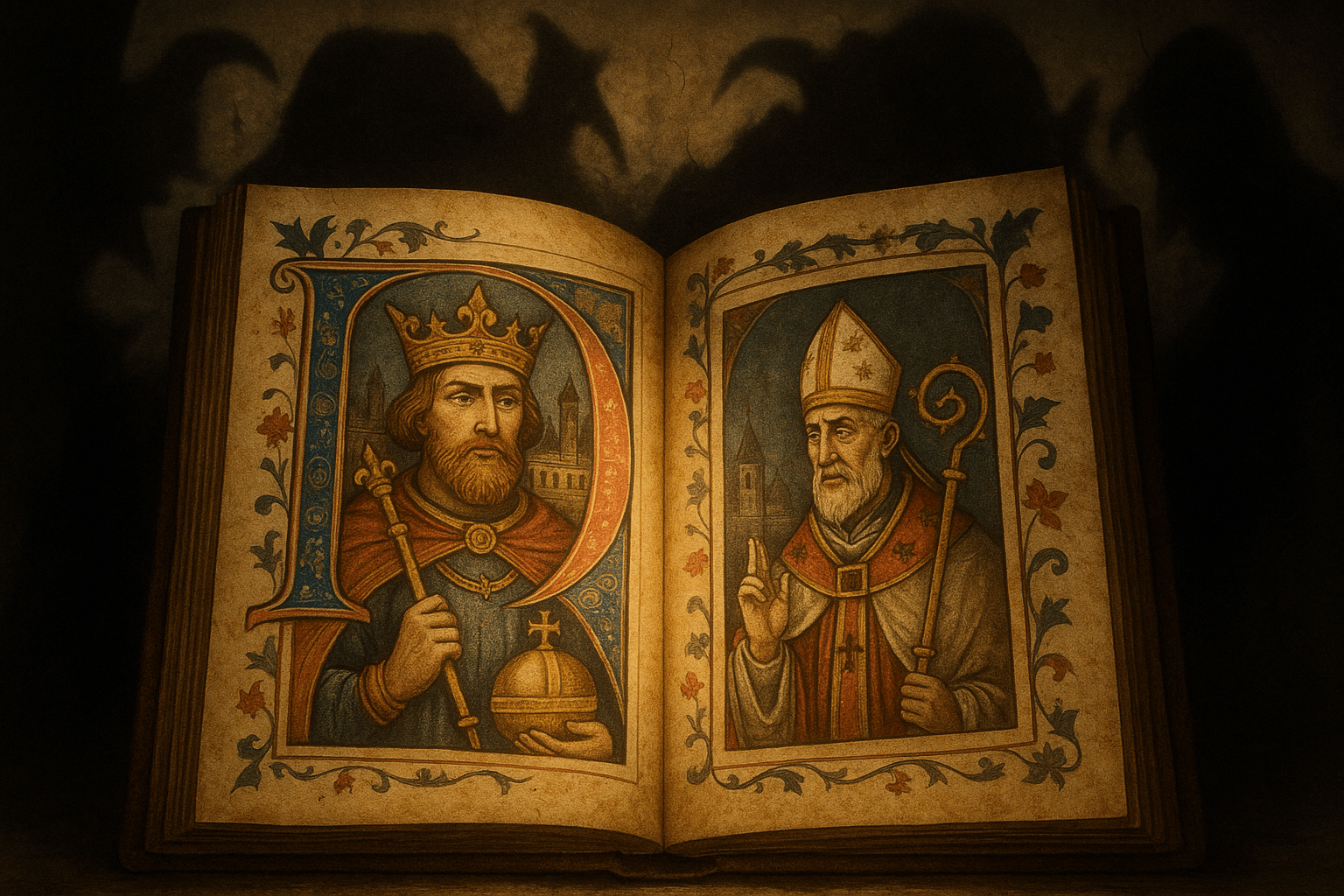

To understand why the Defensor Pacis was intellectual dynamite, we must first understand the world it sought to dismantle. For centuries, popes and emperors had been locked in a struggle for Supremacy. Popes had asserted the doctrine of plenitudo potestatis, or “plenitude of power”, which essentially argued that the pope, as Christ’s vicar on Earth, held ultimate spiritual and temporal authority. Pope Boniface VIII had famously declared in 1302 that it was “absolutely necessary for salvation that every human creature be subject to the Roman Pontiff.”

This was the backdrop for a fierce feud between Pope John XXII and the Holy Roman Emperor, Louis IV of Bavaria. The Pope refused to recognize Louis’s election, and the two were engaged in a war of both arms and words. Marsilius, then a respected scholar and former rector of the University of Paris, decided to weigh in. In 1324, along with his colleague John of Jandun, he secretly completed his masterwork. Its stated goal was to identify the cause of strife and turmoil that plagued Europe and to offer a defense of peace. His diagnosis was shocking: the single greatest threat to peace and order, he argued, was the Papacy’s lust for worldly power.

The Radical Heart of the ‘Defensor Pacis’

The book was divided into three sections, but it was the first, Discourse I, that contained its most revolutionary political Theory. Marsilius didn’t just nibble at the edges of papal authority; he took a sledgehammer to its very foundations with a series of breathtaking arguments.

- The People as Sovereign: In an era of divine right, Marsilius made a claim that sounds almost modern. He argued that the true source of all law and political authority is not God or the Pope, but the people themselves—the whole body of citizens (universitas civium). The king or emperor is merely an elected agent, a servant of the people who is empowered to govern but who can also be deposed by them if he becomes a tyrant. It was one of the earliest and clearest formulations of popular sovereignty in Western history.

- The Church Subordinate to the State: Marsilius ruthlessly applied this logic to the church. He saw the church not as a parallel government, but as a department within the state. Priests and bishops, he argued, have one job: to teach the gospel and administer the sacraments. They should have no coercive power, no right to own vast tracts of land, no courts, and no ability to excommunicate people without the state’s permission. The state, as the representative of the people, should control church finances, appoint its officials, and ensure it serves the common good.

- The Papacy as a Human Invention: This was perhaps his most heretical claim. Marsilius dissected the biblical justifications for papal supremacy and found them wanting. He argued that the Bible gives no indication that Saint Peter was given authority over the other apostles. Therefore, the Bishop of Rome (the Pope) has no God-given authority over any other bishop. The papacy, with its vast bureaucracy and claims to universal monarchy, was not a divine institution, but a historical accident and a human fabrication.

- The General Council as the Ultimate Authority: If the Pope wasn’t in charge of the Church, who was? Marsilius answered: the General Council. This body, representing all believers (the universitas fidelium), was the church’s only supreme authority, capable of interpreting scripture and settling matters of faith. And crucially, he argued that only the secular sovereign—the “human legislator”—had the authority to call such a council.

A Scholar on the Run

Marsilius knew he had written a dangerous book. He and John of Jandun published it anonymously and, when their authorship was inevitably discovered, they had to flee for their lives. Leaving the scholarly haven of Paris, they found refuge in the one place they knew they would be welcome: the court of Pope John XXII’s mortal enemy, Emperor Louis IV.

The reaction from Rome was apoplectic. In 1327, Pope John XXII excommunicated Marsilius, condemning his ideas as “perverse” and “pestiferous.” The scholar was labeled not just a political theorist, but a “son of perdition” and a formal heretic. Marsilius, far from backing down, put his theories into practice. He accompanied Louis on his invasion of Italy in 1328, where the Emperor was crowned in Rome not by the Pope, but in a ceremony “by the authority of the Roman people”, a direct application of Marsilian thought. They even went so far as to install an anti-pope, though the endeavor ultimately failed.

The Long Fuse: From Heresy to Reformation

While Marsilius’s direct political project failed, the ideas in Defensor Pacis had lit a long, slow-burning fuse. The book was too radical for the 14th century, but it never disappeared. Its arguments became the intellectual arsenal for anyone who sought to challenge papal power.

In the 15th century, the Conciliar Movement—a push to establish the authority of church councils over the pope—drew heavily on Marsilian thought. But its true moment came another century later. During the Protestant Reformation, the Defensor Pacis was rediscovered, translated, and printed. Martin Luther, who owned a copy, echoed Marsilius’s arguments when he challenged papal authority and called upon German princes to reform the church.

The book’s influence is starkly visible in the English Reformation. King Henry VIII’s Act of Supremacy, which declared the monarch to be the head of the Church of England, was a perfect real-world application of Marsilius’s theory of a national church under state control. The book provided a powerful, ready-made justification for breaking with Rome.

The Defensor Pacis was more than just a medieval political tract; it was a declaration of a new world. It looked past the intertwined hierarchies of the Middle Ages and envisioned a secular state, grounded in the will of the people, with a church confined to its spiritual role. By denying the divine right of the papacy and championing the power of the community, Marsilius of Padua didn’t just defend the peace—he provided the intellectual blueprint to break the papacy and fundamentally reshape Western civilization.