A Pope, a King, and a Slap Heard ‘Round Christendom

For centuries, Rome was more than a city; it was an idea. As the heart of a fallen empire and the seat of St. Peter’s successor, it was the undisputed center of Western Christendom. The Pope, the spiritual leader of millions, resided there, his authority seemingly as eternal as the city itself. Yet in 1309, the unthinkable happened. The Papacy packed its bags and moved, not for a brief trip, but for what would become a nearly 70-year residency in Avignon, a city in what is now southern France. This period, derisively called the “Babylonian Captivity” by its critics, was not a sudden decision but the explosive culmination of a power struggle that had been simmering for decades.

To understand the move, we must first look at the titanic clash between two colossal figures: Pope Boniface VIII and King Philip IV of France, known as “Philip the Fair.” The conflict began, as many do, over money. Philip, needing funds for his wars, decided to tax the enormously wealthy French clergy. Boniface VIII, a staunch defender of papal authority, responded with fury. He issued a papal bull forbidding secular rulers from taxing the clergy without papal consent.

The battle of wills escalated. Philip retaliated by cutting off the flow of French gold and silver to Rome, crippling the Papacy’s finances. Boniface doubled down, issuing the famous bull Unam Sanctam in 1302. This was one of the most extreme declarations of papal supremacy ever made, stating that “it is absolutely necessary for salvation that every human creature be subject to the Roman Pontiff.”

For Philip, this was an intolerable challenge to his sovereignty. In 1303, he dispatched an army to confront the Pope at his family palace in Anagni, Italy. The event, known as the “Outrage of Anagni”, was shocking. The 86-year-old Boniface was captured, threatened, and allegedly slapped by one of Philip’s men. Though he was freed by the local populace after three days, the proud pontiff died just a month later, likely from the shock and humiliation. The Papacy had been physically assaulted by a king, and its mystique of untouchability was shattered.

The Making of a French Pope

The death of Boniface VIII created a power vacuum. His immediate successor lived less than a year, and the subsequent papal election was deadlocked for nearly eleven months between pro-French and pro-Italian factions of cardinals. Finally, in 1305, a compromise was reached: Bertrand de Got, the Archbishop of Bordeaux, was elected and took the name Clement V.

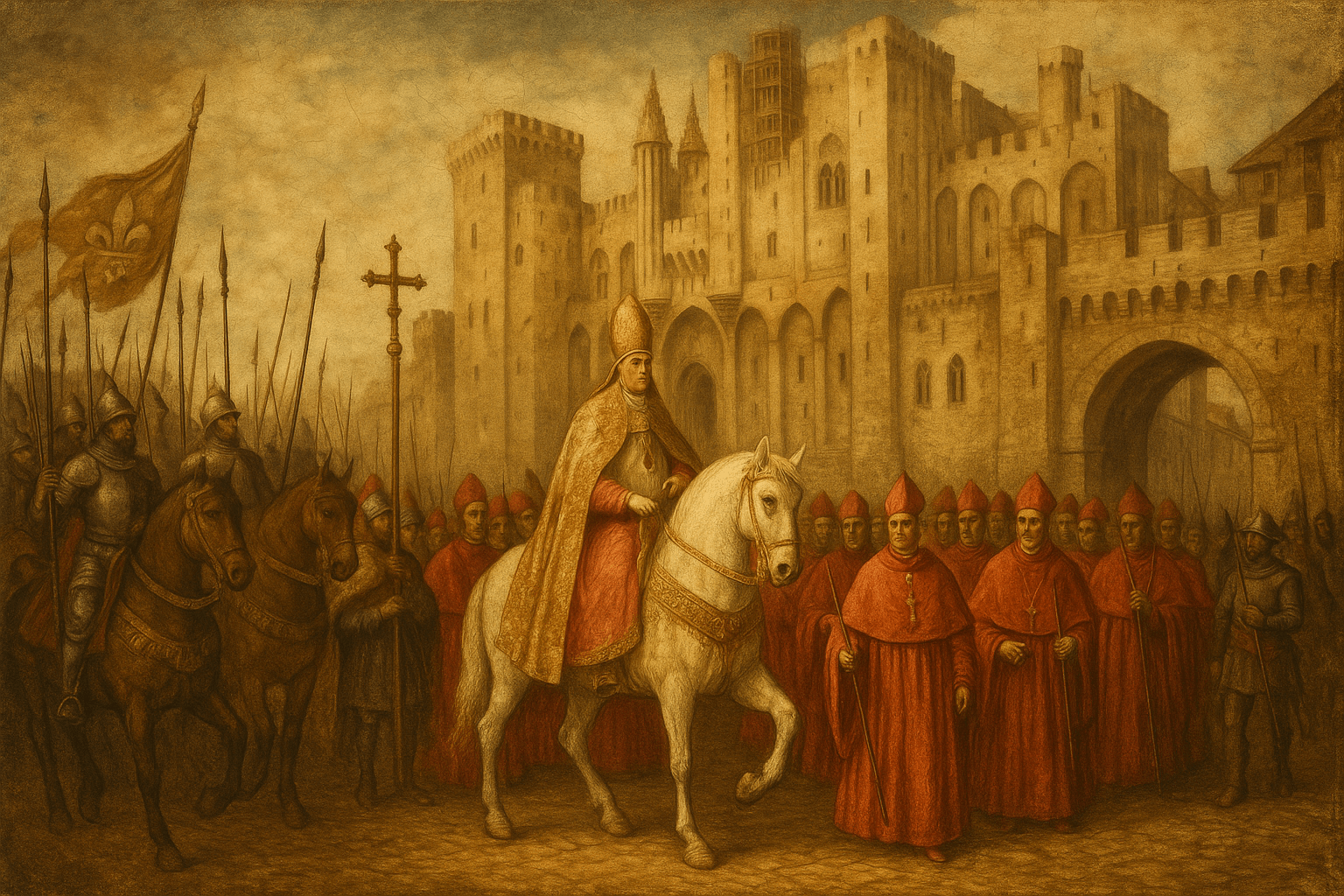

Clement was a Frenchman, a subject of King Philip, and his election was a massive victory for the French monarchy. Citing the violent factionalism and political chaos consuming Rome—a legitimate concern, as rival noble families often turned the city’s streets into battlegrounds—Clement V made a fateful decision. He never traveled to Rome. Instead, he was crowned in Lyon, France. For the next few years, the papal court wandered through France before finally settling in Avignon in 1309.

Avignon was a clever choice. It was technically not part of France at the time, but a territory owned by papal vassals. However, it was nestled on the Rhône River, right next to French territory, effectively placing it under the thumb of the French king. The Pope had moved from the historic seat of St. Peter into a gilded cage.

Life in the “Sinful City”: The Avignon Papacy

The 67 years the papacy spent in Avignon fundamentally altered the institution. The popes who followed Clement V were all French, and their proximity to the French crown led to widespread accusations that they were mere puppets of the king. This perception, whether entirely fair or not, severely damaged the papacy’s international prestige and claim to universal authority.

The most visible symbol of this new era was the construction of the Palais des Papes (Palace of the Popes). Far from a humble spiritual residence, this massive Gothic structure was a fortress and a palace rolled into one. It spoke more of worldly power, wealth, and defense than of spiritual humility. Critics, like the Italian poet Petrarch who lived in Avignon for a time, famously called it the “sinful Babylon”, a hotbed of greed and corruption.

To fund their lavish lifestyle and an increasingly complex bureaucracy, the Avignon popes became masterful administrators and, critics would say, extortionists. They centralized the Church’s administration and perfected new ways to generate revenue:

- Annates: A tax requiring a new bishop or abbot to pay their first year’s income to the Pope.

- Simony: The blatant selling of Church offices.

- Indulgences: The practice of selling forgiveness for sins became far more commercialized.

While this centralization made the Church a more efficient and wealthy organization, it came at a terrible cost. The spiritual authority of the Pope was eroded, replaced by a reputation for avarice and political maneuvering. The focus seemed to have shifted from saving souls to raising funds.

The Long Road Home and an Even Deeper Schism

Throughout the Avignon period, voices across Europe cried out for the Pope to return to Rome. Figures like St. Catherine of Siena and the poet Petrarch passionately argued that the Bishop of Rome belonged in his own diocese. Finally, facing increasing chaos in Italy and persuaded by these powerful appeals, Pope Gregory XI made the journey back to Rome in 1377, ending the Avignon Papacy.

But the story doesn’t end there. Gregory XI died just a year later, and the subsequent election was held in Rome under the immense pressure of a local mob demanding an Italian pope. The terrified cardinals obliged, electing Pope Urban VI.

However, Urban VI proved to be an abrasive and tyrannical reformer. The French cardinals, regretting their decision, fled Rome, declared the election invalid due to duress, and elected their own pope, Clement VII, who promptly returned to Avignon. This was the beginning of the Great Western Schism (1378-1417), a catastrophic period where the Catholic Church had two, and eventually three, rival popes, each claiming to be the one true successor to St. Peter and excommunicating the others.

The “Babylonian Captivity” was over, but its legacy was a Church torn in two. The move to Avignon, born from a struggle over power and money, had set in motion a chain of events that irrevocably damaged the prestige of the Papacy. It exposed the institution as a political entity subject to the pressures of kings and nations, shaking the faith of millions and planting the seeds of discontent that would, a century later, blossom into the Protestant Reformation.