Forget gold, silver, or the fragrant allure of spices from the East. The real treasure that fueled Europe’s first major expansion into the New World was gray, ugly, and smelled faintly of the sea. It was the Atlantic cod—a fish so abundant and so perfectly suited for preservation that it became the unassuming engine of an empire, building fortunes, feeding nations, and weaving together the continents of the Atlantic world.

Long before tobacco fields or sugar plantations dominated the colonial landscape, it was the quest for cod that drew thousands of European ships across the treacherous ocean. This was the original North American gold rush, and its prize wasn’t shiny but salted, dried, and utterly essential.

The Perfect Commodity

Why cod? The answer lies in a unique combination of biology and economics. The North Atlantic cod, Gadus morhua, was incredibly prolific, gathering in massive shoals on the shallow continental shelves off the coast of North America, particularly the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. Just as importantly, cod is a lean fish with very low fat content distributed throughout its flesh. This biological quirk made it the perfect candidate for preservation.

By salting and air-drying the fish, it could be transformed into a hard, lightweight, protein-rich plank that could last for years without refrigeration. In an era before modern food preservation, this was revolutionary. This “salt cod” became the fuel for a rapidly changing Europe. It fed the continent’s growing urban populations, stocked the larders of navies and merchant fleets, and provided a cheap, reliable source of protein for Catholics on the more than 150 meatless days in the religious calendar, including every Friday and all of Lent. Cod was, in essence, the perfect MRE (Meal, Ready-to-Eat) of the 16th century.

A Secret No More: The Race to the Grand Banks

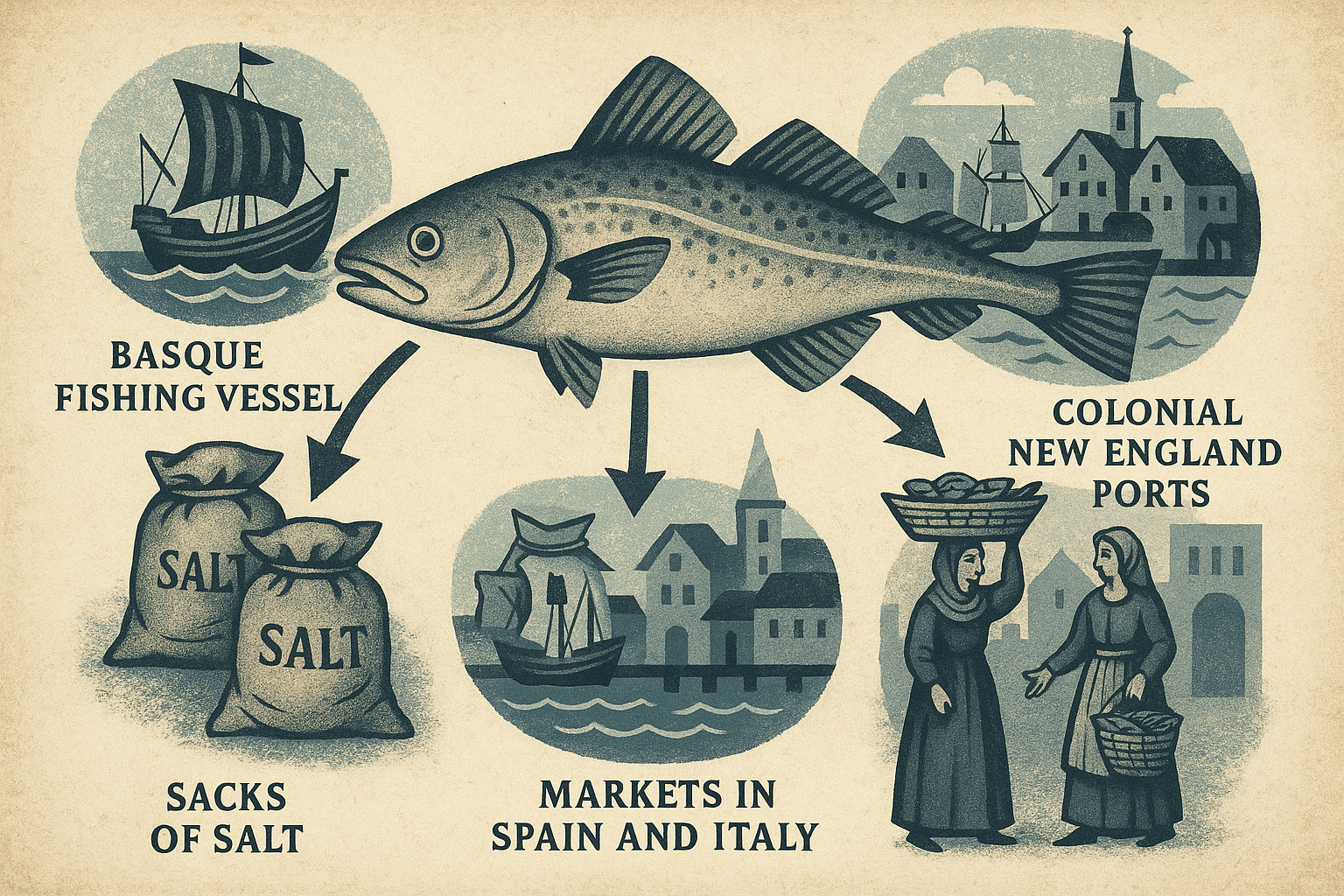

While Scandinavian Vikings certainly fished for cod during their brief settlement in North America around 1000 CE, it was the Basque fishermen of Spain and France who were the true pioneers of the commercial cod trade. Masters of the sea, they had been hunting whales and fishing in the rough waters of the Bay of Biscay for centuries. Though concrete proof is elusive, many historians believe Basque fleets were making secret, annual voyages to the Grand Banks to fish for cod before Columbus’s famed voyage in 1492.

What was a well-guarded secret became an international free-for-all after the explorer John Cabot, sailing for England in 1497, returned with astonishing news. He reported that the waters off Newfoundland were so “swarming with fish” that they could be caught not just with nets, but with baskets weighted down with a stone. The secret was out. Within a decade, fleets from Portugal, France, Spain, and England were making the annual journey, igniting a fierce competition that would shape the destiny of North America.

Building Settlements, One Fish at a Time

The competition for cod created distinct national strategies that directly influenced settlement patterns. The methods for curing the fish determined just how attached a nation became to the land itself.

- The French & Portuguese “Green Cure”: These fishermen often practiced a “wet” or “green” cure. They would heavily salt their catch in the ship’s hold and bring it back to Europe without fully drying it. This required vast amounts of salt but less time on land, leading them to establish small, seasonal shore stations for processing but not large, permanent colonies.

- The English “Dry Cure”: The English, particularly those sailing from the West Country, preferred the “dry cure.” This involved lightly salting the fish and then drying it for weeks on wooden racks called flakes set up on the rocky beaches of Newfoundland and, later, New England. This method produced a superior, harder product that fetched a higher price in European markets. However, it required a significant onshore presence for weeks or months at a time, paving the way for seasonal fishing stations to evolve into permanent settlements. The fishing village of St. John’s, Newfoundland, and the coast of Massachusetts owe their origins to the need for land to dry fish.

The Codfish Triangle: A Global Economic Web

The cod trade didn’t just spur settlement; it created a complex and highly profitable system of triangular trade that became the backbone of the Atlantic economy. New England, in particular, rose to prominence on the strength of this trade.

This “Codfish Triangle” operated in three parts:

- Prime Cod to Europe: The highest-quality, hard-dried cod from New England was shipped to Catholic southern Europe, especially Spain, Portugal, and their Mediterranean colonies. The revenue from these sales—paid in cash, wine, salt, and manufactured goods—was the primary source of wealth for the Boston merchant elite.

- “Refuse” Cod to the Caribbean: The lower-quality fish—broken, undersized, or poorly cured—was not wasted. This “refuse cod” was shipped to the Caribbean, where it became the primary protein source for the enslaved African populations laboring on the brutally profitable sugar plantations.

- Sugar and Molasses to New England: The ships would then carry Caribbean sugar, salt, and, most importantly, molasses back to New England. This molasses was distilled into rum, which was used for local consumption and as a key trade item, including in the transatlantic slave trade.

This network was ingenious and ruthless. The humble cod of Massachusetts fed the enslaved people who produced the sugar that made the rum that fueled further trade. The cod’s importance to the Massachusetts Bay Colony cannot be overstated; its legacy hangs today in the Massachusetts State House in the form of a carved wooden effigy: the Sacred Cod.

The Fall of King Cod

For centuries, the cod seemed limitless. But the very industry it created eventually led to its downfall. The fishing grounds were a constant source of international friction, contributing to conflicts like the Seven Years’ War and the American Revolution. As fishing technology advanced in the 20th century, with the introduction of engine-powered trawlers and massive factory ships, the pressure on cod stocks became unbearable.

The seemingly infinite resource was finite after all. In 1992, the Canadian government was forced to declare a complete moratorium on fishing the Northern Cod stock on the Grand Banks, which had collapsed by over 99%. An industry that had thrived for 500 years and supported tens of thousands of people vanished overnight. It was one of the most profound ecological disasters of modern times.

The story of the cod trade is a powerful reminder of how a single natural resource can shape human history, building economies and empires across an ocean. It’s a story of global connection and immense wealth built on the back of a fish, and a cautionary tale about the devastating consequences of taking nature’s bounty for granted.