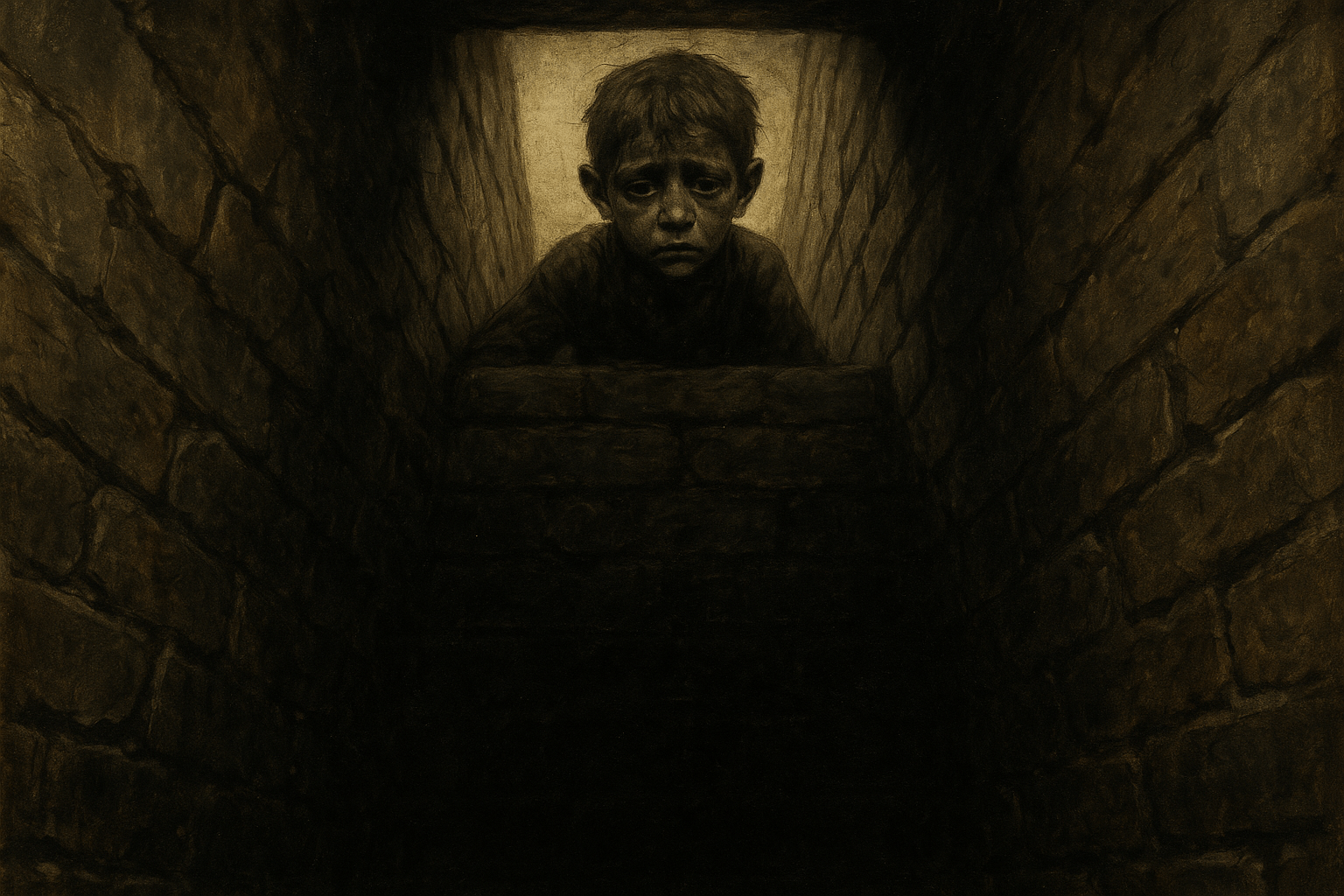

Imagine a Georgian or Victorian townhouse on a cold London evening. Inside, a family gathers around a roaring fire, its warmth a bastion against the chill. This picture of domestic bliss, a cornerstone of the era, was made possible by a dark and suffocating secret hidden within the very walls of the home: the brutal labour of the ‘climbing boys’. These were not men, but small children, some as young as four years old, forced to ascend the narrow, soot-choked chimneys that were the arteries of these new homes.

Why Children? The Rise of the Climbing Boys

The story of the climbing boys begins, ironically, with a disaster meant to improve safety. After the Great Fire of London in 1666, building regulations were changed to make homes more fire-resistant. Houses were built with brick and stone, and chimneys became an integral part of their design. To improve the ‘draw’ of smoke and reduce fire risk, these chimneys were often built with numerous narrow, twisting flues. By the Georgian era, a typical chimney flue might be as narrow as 9 inches by 9 inches (23×23 cm)—far too small for an adult to navigate.

Yet, these chimneys needed frequent cleaning. An accumulation of highly flammable soot and creosote could easily lead to a devastating chimney fire. The solution was as logical as it was horrific: send a child small enough to fit. Master sweeps, who ran the chimney cleaning businesses, began to ’employ’ children for this perilous task. They would acquire boys (and occasionally girls) from impoverished families, orphanages, and workhouses, often ‘buying’ them for a few pounds or taking them on as apprentices. These children were powerless, cheap, and tragically, expendable.

A Life of Soot and Suffering

The life of a climbing boy was one of relentless misery and danger. Their workday began before dawn, and they would be sent out in all weathers to service the homes of the wealthy and middle classes. A master sweep might have several boys, and their call of “Soot-O!” or “Sweep-sweep!” would echo through the pre-dawn streets.

The ‘training’ was barbaric. A new, frightened boy would be forced up his first chimney. If he hesitated, the master sweep might prod his feet with a poker or, in a practice known as “lighting a fire under them”, would place burning straw in the fireplace to force him upwards with the heat and smoke. Their small bodies served as human brushes. They would scrape the soot from the flue walls with a hand scraper and their own elbows and knees, sending it tumbling to the hearth below. The air was thick with blinding, choking dust.

The immediate dangers were terrifying:

- Getting Stuck: A boy could easily get wedged in a narrow or angled part of the flue. If he couldn’t be pulled out, a wall would have to be broken down. In the worst cases, the boy would suffocate before he could be reached.

- Suffocation: Dislodged soot could cascade down, burying a boy and filling his lungs.

- Falls: Crumbling mortar or a loss of grip could send a child tumbling down the chimney, resulting in broken bones or death.

- Burns: Boys were frequently sent up chimneys that were still hot, leading to severe burns on their hands, knees, and feet.

Even if a boy survived his daily climbs, the long-term health consequences were catastrophic. The constant inhalation of soot led to respiratory diseases and lung damage. Their growth was often stunted from malnourishment and the unnatural positions they were forced into. Perhaps most infamously, they suffered from a condition that became known as “Chimney Sweep’s Cancer.” This was a painful and often fatal scrotal cancer, caused by the carcinogenic soot becoming lodged in the folds of their skin. It was the first occupationally-linked cancer ever discovered, a grim medical milestone.

Voices of Protest: The Campaign for Reform

While this practice was widespread, it did not go unnoticed or unopposed. From the late 18th century, a growing movement of social reformers began to shed light on the boys’ plight. Philanthropists like Jonas Hanway and David Porter wrote pamphlets and gave evidence to Parliament about the horrors they witnessed.

The cause was famously taken up in a popular poem by William Blake. His 1789 poem, “The Chimney Sweeper”, from Songs of Innocence, captures the heartbreaking naivety of a young boy who dreams of an angel setting the sweeps free: “And the Angel told Tom, if he’d be a good boy, / He’d have God for his father & never want joy.” The later version in Songs of Experience (1794) is far bleaker, a furious critique of a society that builds its heaven “on the misery of its children.”

Later, in 1863, Charles Kingsley’s novel The Water-Babies played a crucial role in shaping public opinion. The story of Tom, a young sweep who escapes his brutal master by transforming into a magical “water-baby”, was a powerful piece of social commentary disguised as a children’s fairy tale. It brought the grim reality of the climbing boys into the nurseries and drawing rooms of the very people whose chimneys they cleaned.

The Long Road to Abolition

Despite the growing public outcry, legislative reform was agonizingly slow. The master sweeps formed a powerful lobby, arguing that mechanical brushes were ineffective and that banning climbing boys would lead to more chimney fires. Several early laws were passed, but they were weak and poorly-enforced.

The 1834 Chimney Sweepers Act made it illegal to take an apprentice under the age of ten, but it was largely ignored. The 1840 Act, championed by the tireless reformer Lord Shaftesbury, raised the minimum age to 21, effectively trying to ban the practice. But with no real enforcement mechanism, master sweeps simply ignored the law, and magistrates were reluctant to convict them.

The final turning point came in 1875 with the death of 12-year-old George Brewster in Cambridge. He became stuck in a chimney at Fulbourn Hospital. His master, William Wyer, was sent for, but by the time a wall was knocked down, George was dead. The subsequent manslaughter conviction of Wyer caused a national scandal. Lord Shaftesbury, incensed that this was still happening decades after his earlier efforts, seized the moment. He pushed through the Chimney Sweepers Act of 1875. This final, effective law required all chimney sweepers to be licensed and gave the police the power to enforce the ban on climbing boys. By the end of the 19th century, the era of the climbing boys was finally over.

The story of the climbing boys stands as a stark and tragic chapter in Britain’s history. It is a powerful reminder of the hidden human cost of industrialization and urban growth, and a testament to the long and difficult struggle for children’s rights. We remember them not just as victims, but as a crucial part of the story that forced a society to look into the darkness of its own chimneys and finally demand change.