The Dawn of an Oceanic Ambition

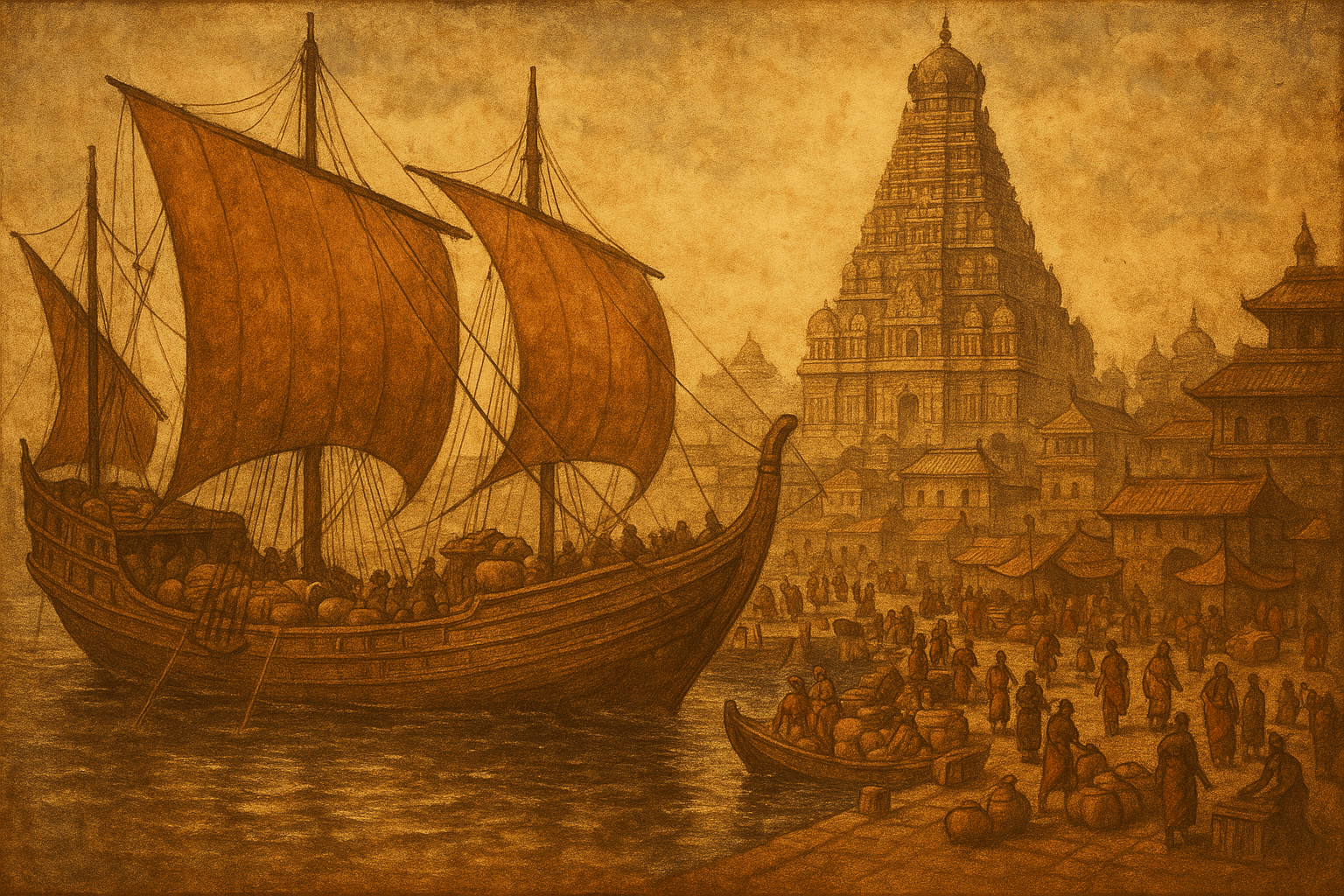

The Cholas were an ancient Tamil dynasty, but their golden age as an imperial power began in the 9th century CE. From their heartland in the fertile Kaveri River delta on the Coromandel Coast, they were perfectly positioned to look eastwards. With access to major ports like Kaveripattinam and Nagapattinam, the sea was not a barrier but a highway. Their ambition was fueled by one of history’s most powerful motivators: control over lucrative trade.

The Indian Ocean was the bustling main street of the medieval world. Spices, gems, aromatic woods, and fine textiles moved from Southeast Asia and China to the Arabian Peninsula, and from there to Europe. The Cholas understood that to become truly powerful, they needed to dominate this flow of wealth. This wasn’t a passive ambition; it required the construction of one of the most sophisticated and powerful navies of its time.

Masters of the Monsoon Seas: The Chola Navy

The Chola navy was the backbone of their empire. It was a permanent, professional, and state-funded force, consisting of a vast fleet of ships. Inscriptions and literary sources describe various types of vessels, from large, multi-decked transport ships called navis capable of carrying hundreds of soldiers and even war elephants, to smaller, more agile warships used for tactical engagements.

But their strength wasn’t just in numbers. The Cholas were master mariners who had an intricate understanding of the monsoon winds—the seasonal weather patterns that dictated all maritime activity in the Indian Ocean. Their navigators used celestial navigation and detailed nautical charts to undertake long and arduous voyages. Their navy enabled them to:

- Protect their own merchant fleets.

- Project military power far from their shores.

- Establish and control strategic trading posts.

- Launch large-scale amphibious invasions.

For a time, the Bay of Bengal was so effectively dominated by their fleet that it was often referred to in foreign accounts as “The Chola Lake.”

The Island Fortress: The Conquest of Sri Lanka

The first major display of the Cholas’ amphibious power was the invasion of Sri Lanka. The great Chola emperor Rajaraja I (r. 985-1014 CE) saw the island as both a strategic threat—due to an alliance between Sri Lanka’s Anuradhapura kingdom and the rival Pandya dynasty—and an economic prize, famed for its pearl and gem fisheries.

Around 993 CE, Rajaraja I launched a naval expedition, conquering the northern half of the island and renaming it Mummudi Chola Mandalam. The Cholas sacked the capital of Anuradhapura and established their own provincial capital at Polonnaruwa. His son, the even more ambitious Rajendra I (r. 1014-1044 CE), completed the job, launching a massive invasion that brought the entire island under Chola dominion for several decades. This conquest demonstrated their ability to sustain long-term overseas military occupations, a feat few medieval kingdoms could manage.

The Great Gamble: Showdown with Srivijaya

The crowning achievement of the Chola navy, and arguably one of the most audacious naval campaigns in world history, was the expedition against the Srivijayan Empire in 1025 CE.

Srivijaya, based in Sumatra (in modern-day Indonesia), was a thalassocracy in its own right. It controlled the Malacca and Sunda straits, the critical maritime chokepoints between India and China. For years, Srivijaya had profited by levying heavy tolls on passing ships. As Chola trade with Song Dynasty China boomed, these tolls became a major point of friction. When diplomacy failed, Rajendra I decided on a direct, decisive, and shockingly bold military solution.

He assembled a massive fleet and launched a surprise attack across thousands of miles of open ocean. This was not a simple coastal raid; it was a full-scale invasion targeting the heart of another major naval power. The Chola navy swept through the straits, attacking and plundering key Srivijayan ports one by one, including its capital, Kadaram (likely the modern-day Kedah region in Malaysia).

The Cholas did not permanently annex Srivijaya. The goal wasn’t occupation but a demonstration of power. The campaign shattered Srivijaya’s naval monopoly, secured Chola trade routes to the East, and cemented Chola hegemony over the entire Indian Ocean trade network. It was a stunning geopolitical victory that resonated across Asia.

Temples of Power: The Legacy in Stone

The immense wealth generated by this maritime dominance was not simply hoarded. The Chola emperors reinvested it in magnificent cultural projects, most notably their awe-inspiring temples. These were not just places of worship but also sprawling economic and social centers that housed schools, hospitals, markets, and administrative offices.

The most famous example is the Brihadeeswarar Temple in Thanjavur, built by Rajaraja I. A UNESCO World Heritage site, its main tower soars to a height of 66 meters (216 feet) and is capped by a single stone block weighing an estimated 80 tons. It stands as a testament to Chola engineering, artistry, and the sheer scale of their ambition.

Not to be outdone, Rajendra I built his own capital, Gangaikonda Cholapuram, and a magnificent temple to commemorate his victorious expedition to the Ganges River. The wealth from the Srivijayan campaign was funneled directly into these architectural marvels, turning the Chola heartland into a landscape of divine grandeur.

Conclusion: An Empire That Ruled the Waves

The Chola dynasty’s naval empire eventually declined due to internal strife and the rise of rival powers. Yet, for over two centuries, they were the undisputed masters of the Indian Ocean. Their story challenges the Eurocentric view of maritime history and reveals a world where Indian sailors, soldiers, and sovereigns projected power across vast oceanic distances.

From the shores of Southern India to the straits of Indonesia, the Cholas left a legacy of conquest, commerce, and culture. Their magnificent temples still stand as silent witnesses to an age when their fleets ruled the waves, their merchants dominated trade, and their emperors built an empire funded by the riches of the sea.