The Rise of an Empire in the Desert

Emerging from the cultural ashes of the Moche civilization, the Chimú kingdom began its rise in the Moche Valley. According to legend, their dynastic founder, a hero named Taycanamo, arrived from the sea on a balsa raft. He and his descendants steadily expanded their influence, conquering neighboring valleys and smaller polities to forge a centralized empire. By its height in the 15th century, the Chimú state, known as Chimor, was the primary rival to the burgeoning Inca state in the highlands.

Their power was consolidated and administered from their capital, Chan Chan. This was not just a city; it was the political, economic, and spiritual heart of the entire empire, a testament to the Chimú’s organizational prowess and an architectural marvel of the pre-Columbian world.

Chan Chan: The Glimmering Adobe Capital

Imagine a city stretching over 20 square kilometers, its high walls catching the desert sun. Chan Chan was a masterpiece of urban planning, constructed almost entirely from mud-bricks (adobe). Instead of a single, unified grid, the city’s core was composed of nine enormous rectangular compounds known as ciudadelas, or “citadels.”

These were no ordinary enclosures. Each ciudadela was a self-contained palace complex, likely built by a successive Chimú king. Surrounded by adobe walls up to nine meters high, they contained temples, residential quarters for the elite, administrative offices, storerooms, and plazas for ceremonies. Most importantly, each citadel also served as the royal tomb for the king who built it. Once the king died and was entombed with his riches and sacrificed retainers, his ciudadela was sealed, and his successor would build a new one.

The walls of these compounds were not left bare. The Chimú decorated them with stunning, intricate friezes. The motifs were a clear reflection of their environment and beliefs: rows of fish, sea birds like pelicans, crashing waves, and fishing nets. These designs, often repeated in a rhythmic, geometric fashion, underscored the profound importance of the Pacific Ocean to their survival and worldview.

Masters of Metal and Mold

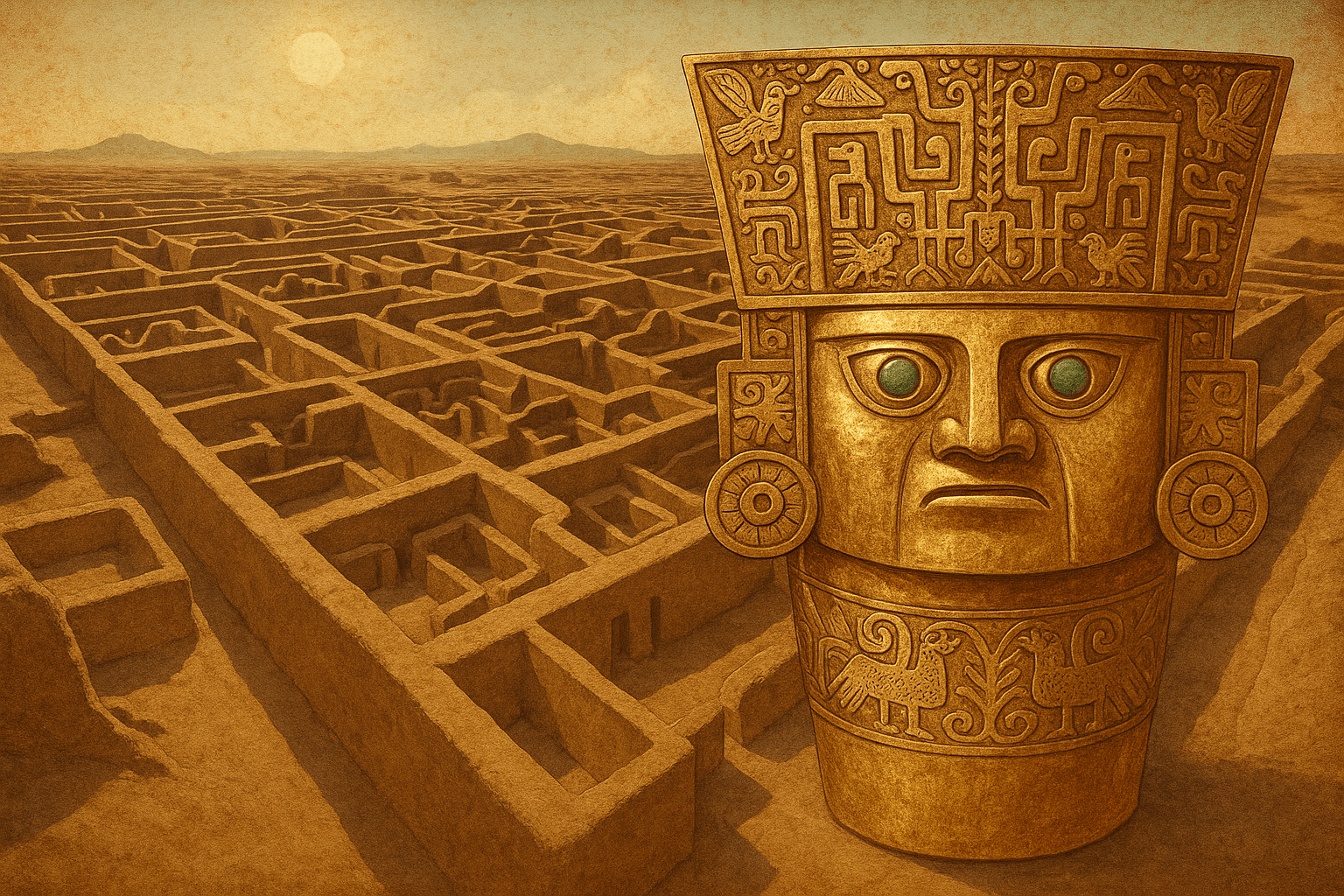

While their architecture was incredible, the Chimú’s reputation for artistry rests firmly on their metalwork and pottery. They were, without a doubt, some of the most accomplished metalsmiths in the ancient Americas.

Chimú artisans inherited techniques from earlier cultures like the Moche but elevated them to new heights. They expertly worked with gold, silver, and copper, mastering complex techniques like:

- Repoussé: Hammering intricate designs onto sheet metal from the reverse side to create a raised pattern.

- Casting: Using the lost-wax method to create complex three-dimensional objects.

- Welding and Gilding: Joining metal pieces and applying thin layers of gold or silver for decorative effect.

Their workshops produced breathtaking ceremonial objects, including elaborate burial masks, ornate ear spools, breastplates, and ritual knives known as tumi. These items were not just beautiful; they were symbols of status and divine connection. When the Inca finally conquered the Chimú, they were so impressed that they forcibly relocated many Chimú metalsmiths to their capital of Cusco to produce fine goods for the Inca elite.

In pottery, the Chimú ethos was different. While earlier coastal peoples created individually painted, masterpiece ceramics, the Chimú prioritized efficiency and standardization. They perfected the use of two-part molds, allowing them to mass-produce vessels. Their most iconic style is a sleek, polished blackware, achieved by carefully controlling the oxygen during the firing process. Though forms were standardized, they were far from simple, often featuring molded figures of animals, humans, fruits, and mythological scenes, with the stirrup-spout handle being a common feature.

Taming the Desert: A Feat of Hydraulic Engineering

How did a civilization of tens of thousands thrive in one of the driest places on Earth? The answer lies in the Chimú’s brilliant hydraulic engineering. They understood that water was the ultimate source of power and wealth, and they constructed a vast and intricate network of canals to control it.

These canals, some stretching over 50 miles, diverted water from rivers flowing down from the Andes mountains and channeled it into a grid of agricultural fields. One monumental project, the La Cumbre Canal, was designed to transfer water from the Chicama Valley to the Moche Valley, the location of Chan Chan. This system irrigated vast tracts of land, allowing the Chimú to cultivate maize, beans, squash, and cotton in quantities sufficient to feed their cities and fuel their economy. This agricultural surplus was the foundation upon which their complex society was built.

Society, Belief, and the Inca Conquest

Chimú society was highly stratified, with a divine king at its apex. Below him were nobles, administrators, and a vast class of commoners, including farmers, fishermen, and the artisans who powered the kingdom’s workshops. Their religious life differed significantly from the later Inca. While the Inca revered the Sun (Inti) as their principal deity, the Chimú worshipped the Moon (Si). They considered the Moon more powerful because it could be seen both day and night and believed it controlled the weather and the growth of crops.

This reverence for natural forces sometimes took a grim turn. Archaeological evidence, most notably at a site called Huanchaquito-Las Llamas, has revealed mass child sacrifices. It is believed these horrifying rituals were performed to appease the gods during catastrophic El Niño events, which brought devastating floods and disrupted the marine ecosystem the Chimú depended upon.

Ultimately, the Chimú Empire’s dominance was challenged by the unstoppable expansion of the Inca. Around 1470 CE, the Inca emperor Tupac Inca Yupanqui marched his armies to the Chimú frontier. Instead of a simple frontal assault, the Inca employed brilliant and ruthless strategy: they seized control of the canals in the highlands, effectively cutting off the water supply to Chan Chan and the coastal valleys. Deprived of the very lifeblood of their society, the Chimú were forced to submit. Their king was taken to Cusco, their empire was absorbed, and their great city of Chan Chan began its long, slow decline into a silent, sun-bleached ruin.

Though overshadowed by the fame of the Inca, the Chimú Kingdom was a powerhouse of culture, art, and engineering. Their legacy is etched into the desert landscape—in the ruins of their great adobe city, the glint of their golden treasures, and the ghostly traces of the canals that once made the desert bloom.