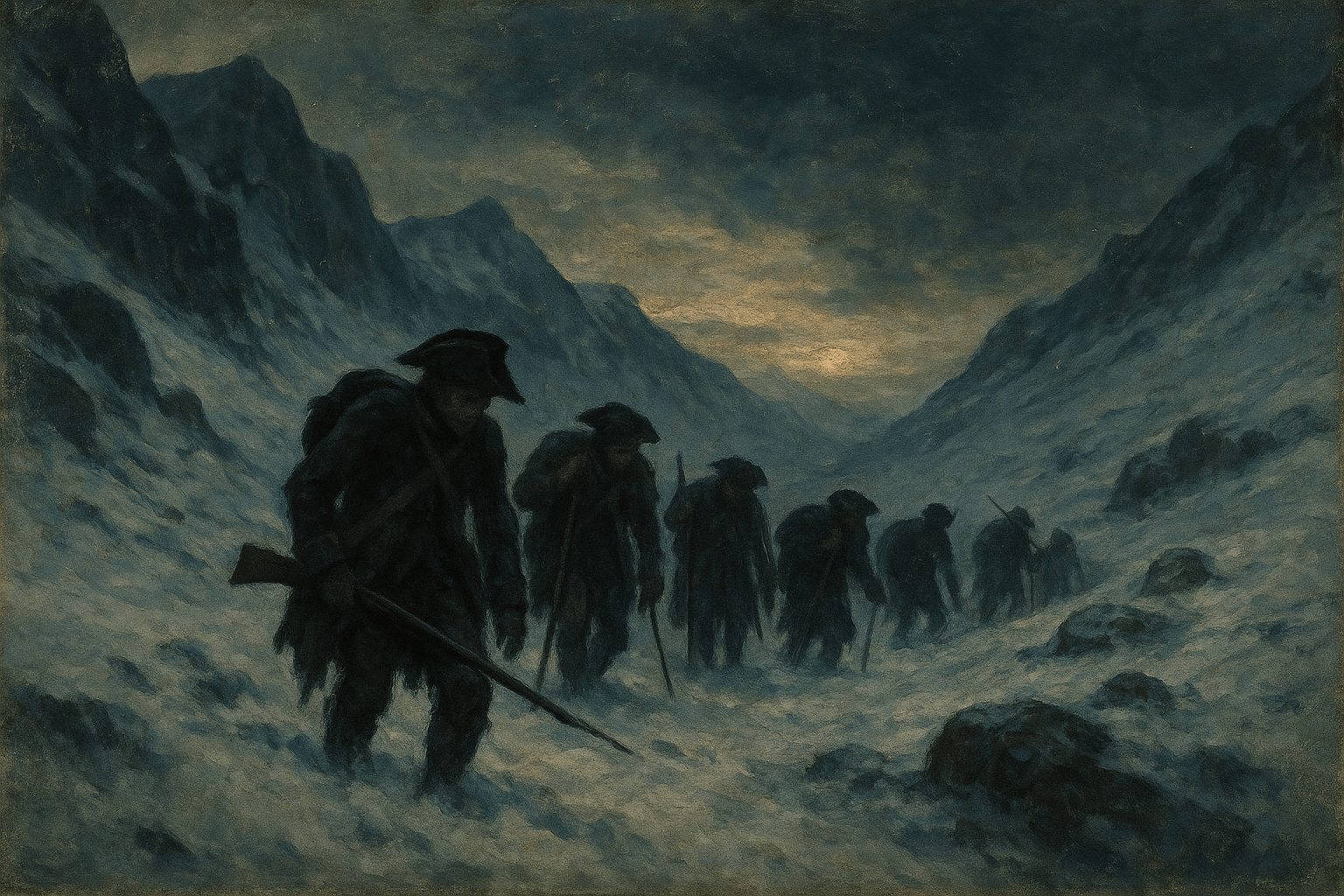

Over just a few days, more than 3,000 Swedish soldiers would freeze to death, their bodies left scattered across the Tydal mountain range. It was a brutal and haunting postscript to the Great Northern War, and a final, icy end to Sweden’s age as a great European power.

The End of an Empire: Context of the Great Northern War

To understand the desperation on that mountain, we must first look at the war that led them there. The Great Northern War (1700-1721) was a sprawling, two-decade conflict that pitted the ambitious Swedish Empire against a powerful coalition including Russia, Denmark-Norway, and Saxony-Poland. At Sweden’s helm was the formidable King Charles XII, a military prodigy known as the “Lion of the North.”

For the first decade of the war, Charles XII seemed invincible, leading his highly disciplined Carolean armies to stunning victories across Europe. The Caroleans were renowned for their “Gå På” (Go On) spirit—an aggressive, shock-and-awe tactic that relied on unwavering discipline and cold steel. But the king’s ambition ultimately outstripped his resources. In 1709, his catastrophic invasion of Russia culminated in a devastating defeat at the Battle of Poltava. The Swedish army was shattered, and Charles XII was forced into a long exile in the Ottoman Empire.

When he finally returned to Sweden in 1715, he found his empire crumbling. Undeterred, he raised new armies and launched a series of desperate campaigns to turn the tide. His final gamble was an invasion of Norway in 1718, which was then part of the kingdom of Denmark-Norway.

The Ill-Fated Norwegian Campaign

Charles XII’s plan was twofold. He would lead the main Swedish army to capture the strategic Fredriksten Fortress in the south, while a second, northern army under Lieutenant General Carl Gustaf Armfeldt would march to capture the vital city of Trondheim. This northern force, comprising over 10,000 men, was known as the Armfeldter Carolean Army.

Armfeldt’s campaign, launched in August 1718, was brutal from the start. The Caroleans were marching through rugged, sparsely populated terrain. Poor weather, stretched supply lines, and fierce Norwegian guerrilla resistance plagued them. They reached the outskirts of Trondheim but, undersupplied and exhausted, were unable to mount an effective siege. As winter set in, the army was forced to dig in, suffering from hunger and disease in the cold Norwegian highlands.

The King is Dead, The Retreat Begins

The entire strategic situation changed in an instant on November 30, 1718. While inspecting his siege lines at Fredriksten Fortress, King Charles XII was struck in the head by a projectile and killed instantly. To this day, historians debate whether the fatal shot came from an enemy rifle or from an assassin within his own ranks.

With the warrior-king dead, the political will for the war evaporated. The Swedish high command immediately gave the order for all forces in Norway to abandon their positions and retreat to Sweden. The news traveled slowly through the winter landscape, reaching General Armfeldt in the Trøndelag region on January 7, 1719.

Armfeldt’s army was in a perilous state. Now numbering just under 6,000 men, his troops were weakened, ill-equipped, and short on food. Faced with a long and difficult journey home, he made a fateful decision. He chose the shortest route: a direct path over the Tydal mountain range, which separated Norway from the Swedish province of Jämtland.

The March into the White Hell

On January 8, 1719, the army began its march from the village of Tydal, guided by a local Norwegian, Lars Bersvendsen Østby. The weather was cold but clear. The guide, familiar with the treacherous and unpredictable nature of the mountains, strongly advised against the crossing, but the Swedish officers, eager to get their men home, overruled him.

The first day of the march was difficult but manageable. By the evening of January 9, the army had reached the barren mountain plateau between the villages of Tydal and Handöl. They were exposed, with no trees for shelter or firewood.

Then, disaster struck. On January 10, a ferocious blizzard, a northwesterly gale known locally as a draup, swept down upon them with blinding speed and fury. The temperature plummeted to an estimated -35°C (-31°F) or colder. In the blinding, swirling snow, visibility dropped to zero. All military order dissolved into a primal struggle for individual survival.

The horrors that unfolded on the mountain are difficult to comprehend:

- Men froze to death where they stood, some were later found as frozen statues, still clutching their muskets.

- Without wood, desperate soldiers set fire to their own rifle stocks and sleds for a few precious moments of warmth.

- Horses succumbed quickly, their frozen carcasses providing a grim, temporary windbreak for huddling groups of men who would also eventually freezesolid.

- Many lost their sight as their eyes froze over. Disoriented and delirious, they wandered off into the white void, never to be seen again.

- Hundreds simply lay down in the snow, succumbing to the final, peaceful embrace of hypothermia. The roaring wind was the only sound that answered their cries.

The storm raged for three days. It was not a battle, but a slaughter at the hands of nature.

The Aftermath: A Frozen Graveyard

When the blizzard finally subsided, the few hundred soldiers who had managed to survive the initial onslaught began a torturous journey towards the Swedish border. On January 12 and 13, the first ragged, frostbitten survivors stumbled into the small Swedish village of Handöl.

The scale of the catastrophe was staggering. Of the roughly 5,800 men who began the retreat over the mountain:

- An estimated 3,000 men froze to death on the mountain itself.

- Another 700 died from their injuries, frostbite, and exhaustion in the following days and weeks.

- Of the approximately 2,100 survivors, around 600 were permanently maimed, having lost fingers, toes, hands, and feet to severe frostbite.

When spring arrived and the snows melted, Finnish ski patrols were sent back onto the mountain to recover the dead. They found a vast, open-air graveyard. Bodies lay everywhere—in huddled groups, scattered alone, piled up behind rocks. It took years to bury all the dead Caroleans.

A Brutal Final Chapter

The Carolean Death March was not a strategically significant event; the war was already lost for Sweden. But it serves as a powerful and tragic symbol of the end of an era. It was the final, agonizing death rattle of the Swedish Empire and its once-feared army.

Today, monuments stand in both Tydal, Norway, and Duved, Sweden, to commemorate the victims. The story is kept alive in local lore and historical reenactments, a somber reminder of the human cost of ambition and the overwhelming power of the natural world. It is a haunting tale of an army that conquered kingdoms, only to be utterly defeated by a winter storm.