A Kingdom Built on Water, Not Earth

Picture an ancient civilization. What comes to mind? Perhaps the stone pyramids of Egypt rising from the sand, or the sprawling agricultural terraces of the Inca in the Andes. For thousands of years, the story of civilization has been tied to the soil—the cultivation of grains like wheat, rice, and corn, which allowed populations to grow, specialize, and build empires. But in the sun-drenched, brackish estuaries of Southwest Florida, a remarkable people turned that model on its head. They were the Calusa, and they built their kingdom not on soil, but on shells.

From roughly 500 CE until the early 18th century, the Calusa dominated the coast from Charlotte Harbor down to the Florida Keys. Their power and complexity rivaled that of agricultural societies across the Americas, yet they never tilled a field or planted a single crop of corn. Why? They didn’t need to. Their environment was one of the most productive marine ecosystems in the world. The labyrinth of mangrove forests, seagrass beds, and tidal flats was a bountiful larder, teeming with fish, shellfish, manatees, sea turtles, and wading birds. The Calusa understood this wealth intimately and harnessed it with incredible ingenuity.

The Shell-Works: Engineering an Empire

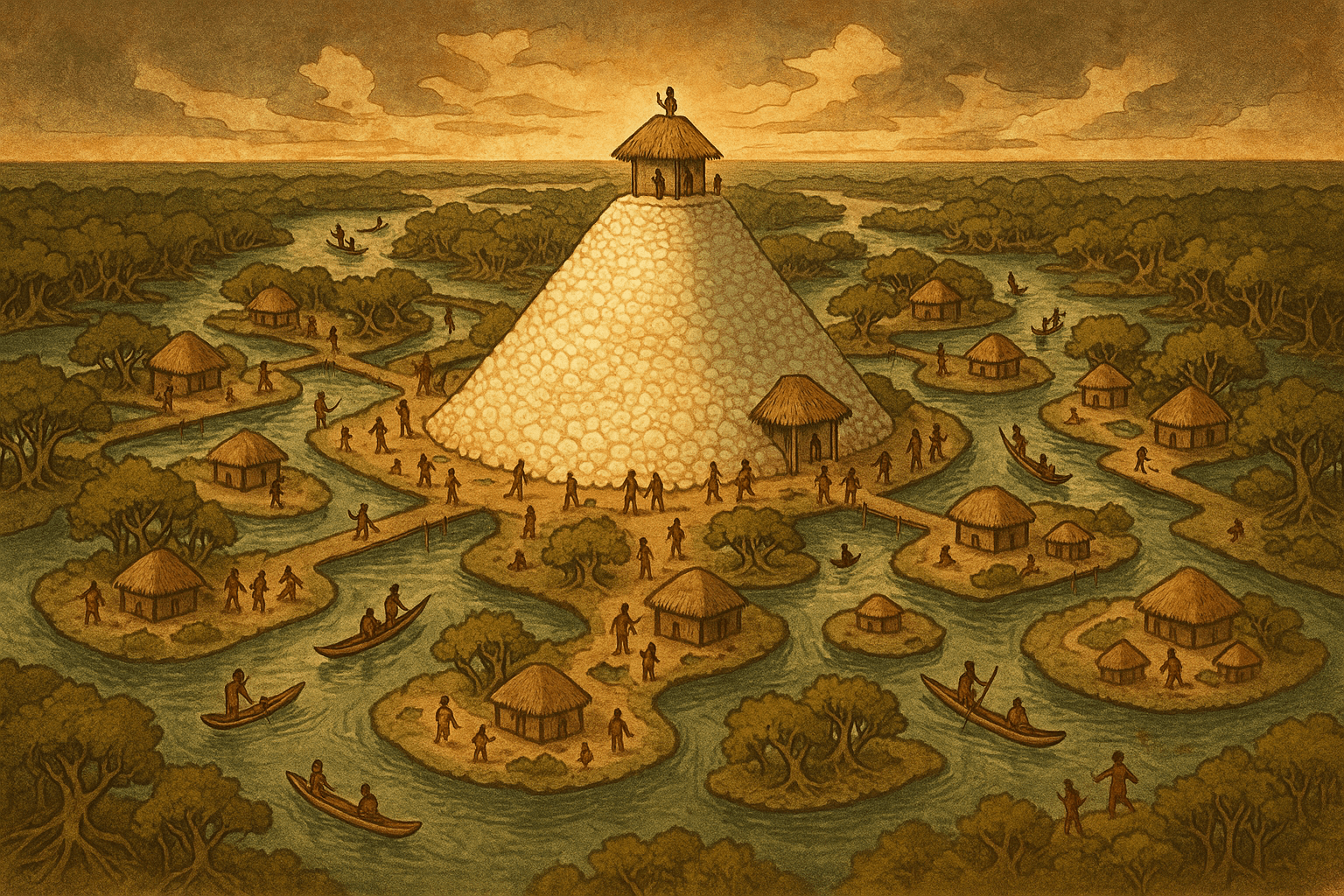

The most visible legacy of the Calusa is their monumental shell-works architecture. These were not mere garbage heaps but deliberately engineered structures that sculpted the very landscape to suit their needs. Living on a low-lying coastal plain meant contending with flooding, storm surges, and insects. The Calusa solution was to build bigger and higher.

Their engineering feats included:

- Shell Mounds: Over centuries, the Calusa piled countless oyster, clam, conch, and whelk shells to create massive mounds. These mounds served as foundations for their towns, elevating important structures above the waterline. The paramount chief’s house, temples, and the homes of the nobility were built atop these high, dry platforms, offering commanding views and a refuge from the swamplands below. Some mounds reached heights of over 30 feet.

- Canals: The Calusa were master canoeists, and they engineered an impressive network of canals to facilitate travel. The most famous, the Pine Island Canal, stretched nearly 2.5 miles across Pine Island, allowing paddlers to cut directly from the calm waters of Matlacha Pass to Pine Island Sound, avoiding a long and potentially dangerous trip around the island. These canals were trade highways and strategic military routes.

- Watercourts: At their capital, Mound Key, archaeologists have discovered large, rectangular features known as “watercourts.” These were likely impoundments for holding fish, acting as giant, managed larders that could be harvested to feed the large population and to provide tribute for the chief.

Mound Key, located in Estero Bay, was the heart of the Calusa kingdom. It is an entirely artificial island complex built of shells, sand, and muck, featuring two major mounds connected by a series of canals and ridges. This was the seat of power, a testament to the Calusa’s ability to literally create their own world from the remnants of their food source.

The Structure of Calusa Society

A society capable of such engineering was, by necessity, highly organized. The Calusa were not a simple collection of fishing villages but a complex chiefdom with a rigid social hierarchy. Spanish accounts from the 16th century describe a society with distinct classes:

- The Paramount Chief: At the top was the hereditary ruler, known as the “Calusa”, from whom the tribe’s name is derived. He held both political and religious authority.

- Nobles and Priests: A noble class, which included the chief’s family and other important leaders, assisted in governing. Priests managed the complex rituals that governed Calusa life.

- Commoners: The majority of the population were commoners, responsible for fishing, gathering, and constructing the great shell-works.

The chief’s power was sustained through an elaborate tribute system. Dozens of subordinate villages throughout South Florida were required to pay tribute to the capital at Mound Key. This tribute wasn’t gold or jewels, but the wealth of the estuaries: dried fish, skins, woven palm-leaf mats, and even captives from other tribes. This system allowed the elite at the capital to focus on politics, war, and ceremony, secure in the knowledge that they would be fed and supplied by their subjects. The Calusa commanded a domain of an estimated 20,000 people at their peak, a powerful political and military force in the region.

Art, Ritual, and a Glimpse of Belief

The Calusa’s artistry was as remarkable as their engineering, especially their work in wood. Because of Southwest Florida’s waterlogged soil, a stunning array of organic artifacts has survived. The most famous of these is the “Key Marco Cat”, a 6-inch-tall wooden sculpture of a feline deity, possibly a panther, depicted in a powerful, half-human stance. Discovered in 1896, its intricate detail and preserved paint offer a rare window into the spiritual world of the Calusa. They also crafted elaborate masks, ceremonial tablets, and tools, demonstrating a sophisticated artistic tradition that belied their non-agricultural lifestyle.

Spanish records note that the Calusa had a complex belief system with three primary deities. The most powerful governed the world, a second ruled human affairs, and the third dictated the outcomes of war. The chief acted as the primary intermediary with these gods, further cementing his central role in society.

Collision with a New World and an Enduring Legacy

In 1513, the Calusa’s world collided with Europe when Juan Ponce de León landed on their shores. Unlike many other indigenous groups, the Calusa were not easily intimidated. They met the Spanish with force, and their initial encounters were violent. For nearly 200 years, the Calusa fiercely resisted Spanish colonization and attempts at religious conversion. Their political organization and military strength allowed them to maintain their autonomy long after other Florida tribes had been decimated.

Ultimately, it was not Spanish swords that brought down the Shell Kingdom. The twin forces of Old World diseases, like smallpox and measles, to which they had no immunity, and raids from other native groups armed by the English to the north, caused their society to collapse in the early 1700s. The last of the Calusa are thought to have fled to Cuba, their kingdom dissolving back into the mangrove estuaries.

Today, the great shell mounds still stand as silent sentinels along the Southwest Florida coast. They are the ghosts of a kingdom, a powerful reminder that the path to civilization is not singular. The Calusa proved that a sophisticated, powerful, and enduring society could be built, not by farming the land, but by mastering the sea and harnessing the profound wealth of its waters.