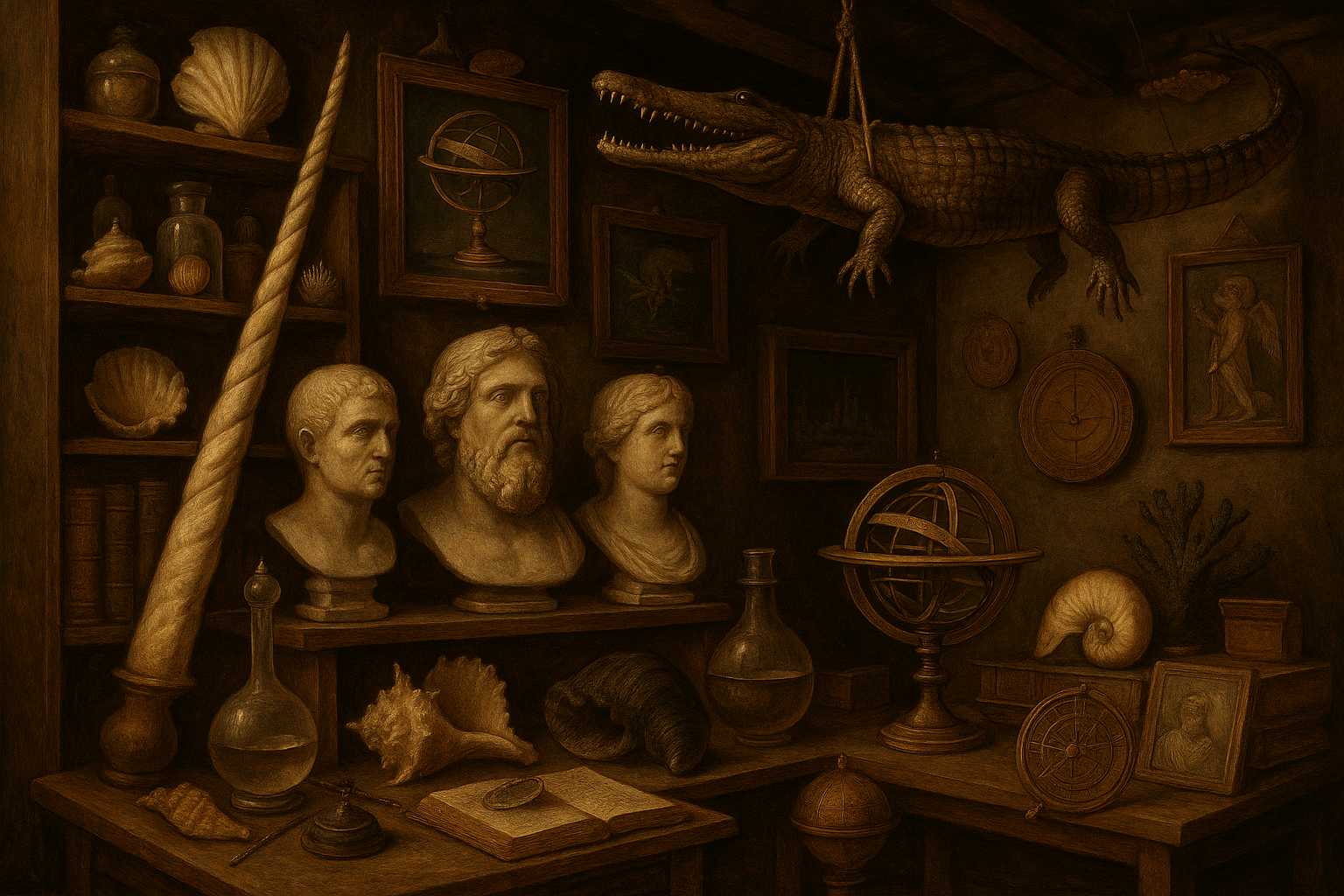

Imagine a room where a polished nautilus shell sits beside a Roman coin, a taxidermied crocodile hangs from the ceiling, and an intricate clockwork automaton shares a shelf with what is claimed to be the horn of a unicorn. This isn’t a fantasy; it was the reality of the Wunderkammern, or “Cabinets of Curiosities”—the fascinating precursors to the modern museum that flourished during the Renaissance and Enlightenment.

Long before museums organized the world into neat, categorized halls of art, science, and history, these private collections served as microcosms of all known knowledge. For the wealthy princes, merchants, and scholars who assembled them, these rooms were theaters of the world, designed to inspire wonder, demonstrate power, and attempt to grasp the sheer diversity of God’s creation.

What Was a “Wonder-Chamber”?

The term Wunderkammer is German for “wonder-chamber”, and these were far more than simple collections of objects. They were an attempt to mirror the structure of the universe on a domestic scale. The collector was not just a hoarder but a scholar and philosopher, creating a physical map of connections between the natural world, human creativity, and the divine. To enter a Wunderkammer was to enter a space of contemplation and intellectual discovery, where the bizarre sat next to the beautiful, and the mundane was made extraordinary through its context.

Unlike today’s public museums, these collections were intensely personal and primarily private. Access was a privilege, granted to fellow scholars, visiting dignitaries, and esteemed friends. Showing off one’s cabinet was a display of intellect, wealth, and global reach. Owning a rare shell from the East Indies or an artifact from the newly explored Americas was a tangible symbol of one’s place in an expanding world.

Categorizing the Cosmos: Naturalia, Artificialia, and Scientifica

While they might seem chaotic to our modern eyes, Cabinets of Curiosities were often organized according to a specific, albeit broad, classification system. The objects within were typically divided into categories that represented the three “kingdoms” of the world.

Naturalia: The Wonders of Nature

This was the domain of all things created by nature. Collectors sought out items that were rare, peculiar, or monstrously beautiful. The goal was to showcase the diversity and occasional strangeness of the natural world.

- Geological specimens: Rare minerals, crystals, oddly shaped stones, and fossils—which were often misinterpreted as the bones of giants or dragons.

- Botanical items: Exotic seeds, strange funghi, and pressed flowers, including the much-prized tulip during the “Tulip Mania” of the 17th century.

- Zoological marvels: This was often the most spectacular part. Collections included preserved snakes, colorful insects, taxidermied armadillos and birds of paradise, skeletons, and marine life like coral, shark teeth (glossopetrae or “tongue stones”), and nautilus shells. The most coveted prize of all was the long, spiraled tusk of a narwhal, almost universally presented as a unicorn’s horn.

Artificialia: The Works of Man

This category celebrated human skill and ingenuity. It contained man-made objects, valued for their craftsmanship, historical significance, or artistic merit.

- Artworks: Intricate miniature carvings from ivory or wood, small paintings, and elaborate jewelry.

- Antiquities: Ancient coins, medals, Roman or Egyptian sculptures, and pottery that connected the Renaissance collector to the classical past.

- Exotica: Ethnographic objects brought back from voyages of discovery. These were particularly prized and included things like Aztec featherwork, Chinese porcelain, Japanese lacquerware, and Turkish daggers.

Scientifica: Instruments of Knowledge

Often considered a subset of Artificialia, this category included the tools that enabled the study of the world and heavens. These objects were both functional and beautiful, representing humanity’s quest for knowledge. Examples included astrolabes, globes, compasses, clocks, microscopes, and telescopes—cutting-edge technology for their time.

The Mind of the Collector

The most famous Cabinets of Curiosities belonged to individuals who were titans of their age. Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II (1552-1612) maintained one of the most legendary collections in his Prague castle. It was an encyclopedic assortment of art, artifacts, and natural wonders, reflecting his deep interest in both science and the occult.

Perhaps the most visually iconic collection is that of Ole Worm, a 17th-century Danish physician. A famous engraving of his Museum Wormianum shows a room CRAMMED with wonders: a crocodile, a polar bear, and various fish hang from the ceiling, while shelves are laden with shells, spears, minerals, and ancient runic artifacts. It is the archetypal image of a Wunderkammer—a space of organized, overwhelming wonder.

In England, the botanist and traveler duo of John Tradescant the Elder and his son, John the Younger, assembled a remarkable collection they called “The Ark.” Their cabinet was unique because it was opened to the public for a small fee, planting the seeds for the public museum. Their motivation was a blend of scientific curiosity and a desire to share knowledge beyond an elite circle.

From Private Wonder to Public Museum

The dawn of the Enlightenment in the late 17th and 18th centuries brought a new emphasis on reason, logic, and systematic classification. The wonderfully chaotic and associative nature of the Wunderkammer began to fall out of fashion. Thinkers like Carl Linnaeus were developing systems for categorizing the natural world with unprecedented scientific rigor.

As a result, the grand, all-encompassing Cabinets of Curiosities were slowly dismantled. Their contents were sorted and separated into the specialized collections that would form the basis of our modern museums. The Naturalia went to natural history museums, the Artificialia to art and ethnographic museums, and the Scientifica to science museums.

The most direct transition is the collection of the Tradescants. Bequeathed to the antiquarian Elias Ashmole, “The Ark” became the foundation of the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford University in 1683—widely considered the world’s first university museum and one of the earliest truly public museums.

Today, the spirit of the Wunderkammer endures. It lives on in our enduring fascination with the unclassifiable, the strange, and the beautiful. It represents a a pivotal moment in history when art and science, magic and reason, were not yet separate worlds, but interconnected parts of a single, marvelous whole. These “wonder-chambers” remind us that the quest to understand our world begins not with neat labels, but with a profound sense of awe.