The Kingdom South of the Border

Long before they ruled Egypt, the people of the Kingdom of Kush—a region often called Nubia, located in modern-day Sudan—shared a deep and complicated history with their northern neighbors. For millennia, the two civilizations were intertwined through trade, war, and cultural exchange. Egyptian influence was strong in Kush; its people worshipped Egyptian gods like Amun, built pyramids (though distinctively steeper and smaller), and adopted Egyptian burial practices.

At times, powerful Egyptian dynasties had colonized parts of Nubia, exploiting its famed gold mines and imposing their culture. At other times, Kush thrived as an independent trading power. By the 8th century BCE, however, the tables had dramatically turned. While Kush was consolidating its power around its capital, Napata, Egypt was in chaos. The once-mighty empire had fractured into a patchwork of competing city-states ruled by rival chieftains. From their southern vantage point, the Kushite kings saw a sacred land in disarray, its ancient traditions and piety neglected. They believed it was their divine mission to intervene.

A Holy Invasion

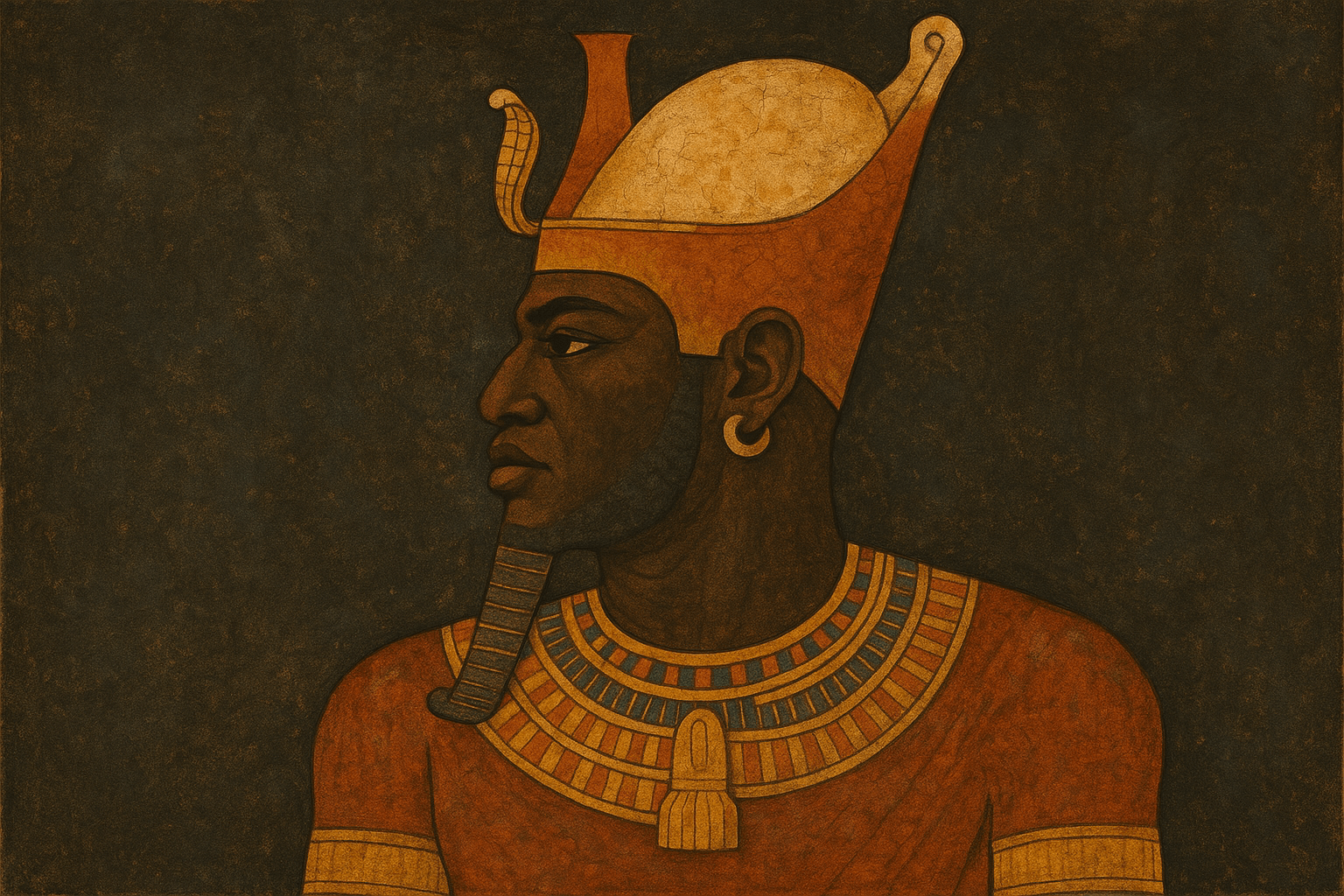

The Kushite king who set this monumental plan in motion was Piye. A devout worshipper of the god Amun, whose main cult center was at Thebes in Upper (southern) Egypt, Piye saw the squabbling northern rulers as illegitimate and impious. In approximately 730 BCE, he launched an invasion of Egypt, but he framed it as a holy war, not a mere conquest for power.

His campaign is meticulously recorded on the “Victory Stele”, a magnificent granite slab he erected in the temple of Amun at Gebel Barkal, the sacred mountain of Kush. The stele describes how Piye’s army swept north, with the king instructing his soldiers to purify themselves before battle because they were fighting for their god. He accepted the surrender of cities like Hermopolis and Memphis, but his ultimate goal was to be recognized as the one true pharaoh, chosen by Amun to reunite the Two Lands of Upper and Lower Egypt.

After defeating the coalition of northern leaders, Piye did something remarkable. Instead of moving his capital to a traditional Egyptian city like Memphis or Thebes, he accepted the fealty of the local rulers, sailed back up the Nile, and returned to his home in Napata. He had accomplished his mission: Egypt was reunified under his authority, and the proper worship of the gods was restored.

Restorers on the Throne

Piye’s successors did not remain distant rulers. His brother, Shabaka, consolidated Kushite control, moved the capital to the ancient Egyptian city of Memphis, and began a remarkable period of cultural renaissance. The Kushite pharaohs of the 25th Dynasty saw themselves not as foreign conquerors, but as restorers of a glorious past. They were, in their own eyes, more Egyptian than the Egyptians.

This commitment to tradition was the hallmark of their reign. They initiated a massive program of building and restoration throughout Egypt, particularly in the religious complex of Karnak at Thebes. They commissioned new chapels, erected statues, and repaired monuments that had fallen into neglect. One of the most famous rulers of this era, Taharqa, left an especially impressive legacy. He is responsible for towering colonnades in the court of Karnak temple and built extensively throughout both Egypt and his native Kush.

The Kushite pharaohs also championed a return to older artistic styles, deliberately emulating the art and architecture of Egypt’s Old and Middle Kingdoms—periods they considered a golden age. They revived ancient religious texts and burial customs, demonstrating a profound respect for the deep-rooted traditions of the land they now ruled.

Clash of Empires: Assyria and the Retreat South

The 25th Dynasty’s ambitious revival took place under the shadow of a new, formidable superpower: the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Based in Mesopotamia, the Assyrians were expanding westward with a ruthless and technologically advanced army, particularly known for its use of iron weapons.

The two empires inevitably clashed over control of the Levant (the lands of the Eastern Mediterranean). The pharaoh Taharqa, mentioned in the Bible as “Tirhakah king of Cush”, initially managed to challenge Assyrian dominance in the region. However, the Assyrians were relentless. In 671 BCE, the Assyrian king Esarhaddon invaded Egypt, defeated Taharqa’s army, and captured Memphis. Taharqa was forced to flee south to Thebes.

Though he briefly recaptured Memphis, the Assyrians returned with a vengeance under a new king, Ashurbanipal. In 663 BCE, the Assyrian army marched south and delivered a devastating blow: they sacked the great city of Thebes, the spiritual heart of both Egypt and the Kushite dynasty. The plunder and destruction sent shockwaves throughout the ancient world.

Taharqa’s successor, Tantamani, made one last valiant attempt to reclaim Egypt, but he was ultimately pushed back. The Kushite pharaohs retreated south, ending their century-long rule over Egypt. The 25th Dynasty was over.

An Enduring Legacy

Though their time as rulers of Egypt was relatively brief, the Black Pharaohs left an indelible mark. They unified a fractured country, sparked a significant cultural and religious revival, and created some of the most impressive architecture of the era. Their rule was a unique moment when an external power didn’t just conquer Egypt, but passionately embraced and revitalized its oldest traditions.

Even after their retreat, the story of the Kushites was far from over. Their kingdom continued to thrive for another thousand years, eventually moving its capital further south to Meroë. There, they continued to build pyramids and worship Egyptian gods, fusing pharaonic traditions with their own distinct Nubian culture. The reign of the 25th Dynasty challenges simplistic narratives about ancient Egypt, revealing a more complex, interconnected African world and proving that the title of “Pharaoh” belonged not just to one people, but to those who held the deepest devotion to the traditions of the Nile.