The Seeds of Treachery

For years, Rome had been pushing its frontier east across the Rhine River, seeking to create a new province, Germania Magna, that would extend all the way to the Elbe River. To govern this new territory, Augustus appointed Publius Quinctilius Varus. Varus was an experienced administrator, but he was a politician, not a frontier general. He was arrogant, tone-deaf to the local culture, and saw the Germanic tribes not as proud warriors to be respected, but as conquered subjects to be taxed and Romanized as quickly as possible. This heavy-handed approach created a deep well of resentment.

Watching this all unfold was a man living in two worlds: Arminius. A prince of the Germanic Cherusci tribe, Arminius had been given to Rome as a hostage in his youth. He was raised in the heart of the Empire, granted Roman citizenship, educated in military strategy, and even achieved the rank of eques (knight). He served with distinction in the Roman army, commanding Germanic auxiliary troops and earning the trust of men like Varus. But while he wore the uniform of Rome, his heart remained with his people. Seeing Varus’s oppressive rule, Arminius began to secretly forge a coalition of Germanic tribes, using his intimate knowledge of Roman tactics to plot their downfall.

The Trap is Sprung

In the autumn of 9 CE, Varus was marching his three legions—the Seventeenth, Eighteenth, and Nineteenth—along with auxiliary cohorts and cavalry, from their summer encampment back to their winter base near the Rhine. The total force numbered close to 20,000 men. Arminius, serving as a trusted advisor, saw his moment.

He approached Varus with a fabricated report of a minor tribal uprising some distance away. He convinced the Roman general to make a “short” detour through unfamiliar territory to crush the rebellion and assert Roman authority. It was the perfect lure. Despite warnings from at least one loyal Germanic noble that Arminius was not to be trusted, Varus’s arrogance and faith in his “Romanized” friend blinded him. He ordered his legions off the known Roman roads and into the Teutoburg Forest.

The terrain was a death trap. Instead of the open fields where Roman formations were unbeatable, the path was a narrow, muddy track winding through dense woods, hills, and marshes. To make matters worse, a torrential downpour began. The storm turned the ground into a quagmire, slowing the Roman column to a crawl and stretching it out over a staggering 15-20 kilometers. The soldiers’ large shields became waterlogged and heavy, and their bowstrings were rendered useless by the damp.

Annihilation in the Forest

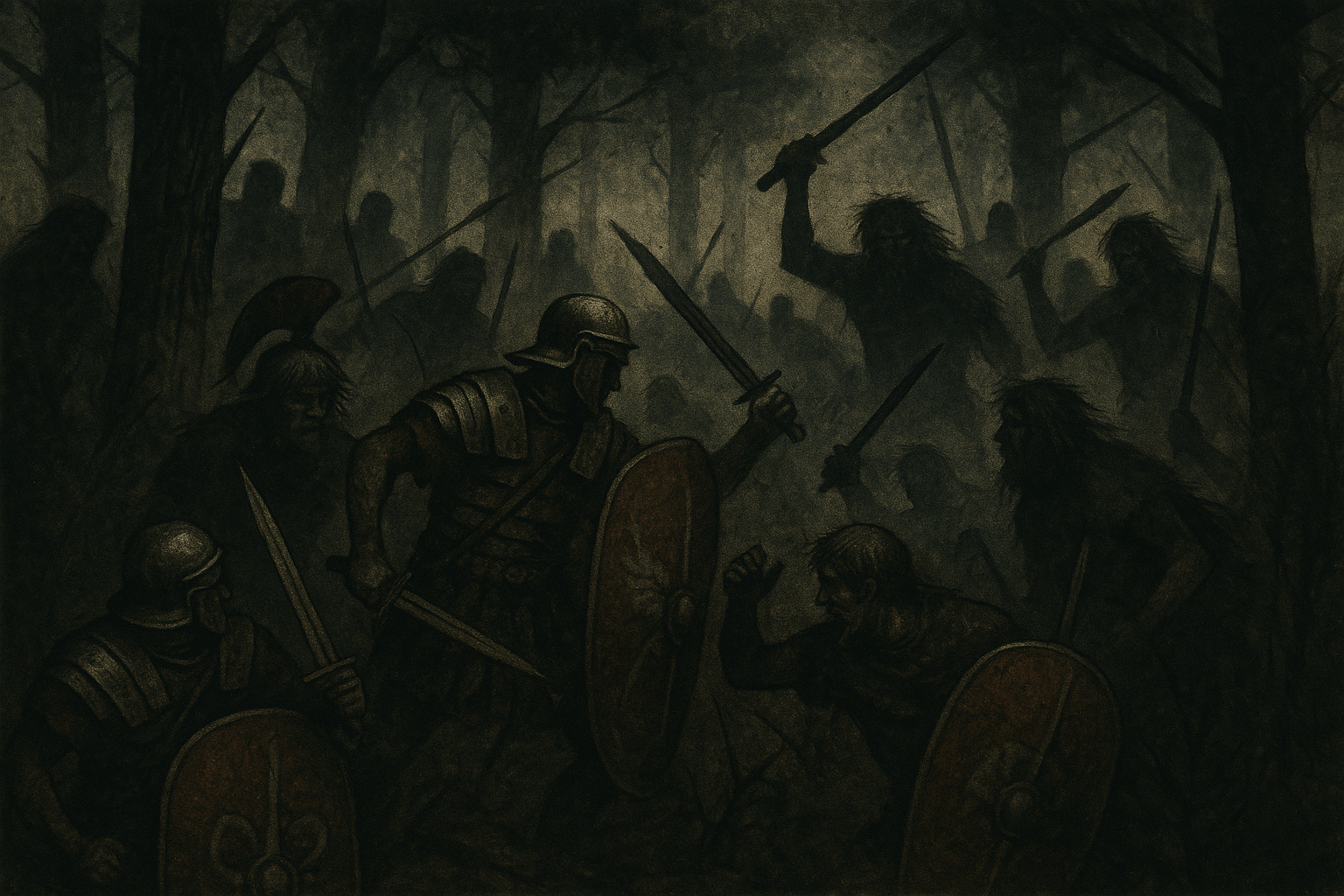

As the exhausted and disorganized Roman column entered a prepared chokepoint, Arminius slipped away and gave the signal. Thousands of Germanic warriors, who had been hiding behind a pre-built earthen rampart and in the dense foliage, unleashed hell. A storm of javelins, spears, and arrows rained down on the surprised Romans.

Chaos erupted. The Romans’ greatest strengths were instantly nullified:

- Lack of Formation: Stretched out in a long, thin line, they could not form their famous testudo (tortoise) shield wall or organized battle lines.

- Constricted Terrain: The narrow path prevented them from deploying their superior numbers or cavalry effectively.

- Logistical Nightmare: The massive baggage train, filled with supplies and the families of soldiers, became an obstacle, blocking any retreat and adding to the panic.

The battle devolved into a brutal, three-day running fight. The Romans were fighting not as a unified army, but as small, desperate groups, bogged down in mud and surrounded by an enemy that knew every inch of the terrifying terrain. At night, they would attempt to form a makeshift fortified camp, only to be harassed and worn down further. On the final day, seeing that the situation was utterly hopeless, Varus fell on his own sword, a traditional Roman way for a commander to avoid the dishonor of capture. Most of his senior officers followed his example. The remaining soldiers were mercilessly hunted down and slaughtered. In the ultimate humiliation for Rome, all three of the legions’ sacred eagle standards—the aquilae—were captured by the tribes.

The Aftermath: “Varus, Give Me Back My Legions!”

When news of the disaster reached Rome, the city was thrown into a state of panic. The Emperor Augustus, now an old man, was reportedly devastated. According to the historian Suetonius, he would wander his palace for months, unshaven and unkempt, banging his head against the walls and crying out:

“Quinctili Vare, legiones redde!” (Quinctilius Varus, give me back my legions!)

The military loss was catastrophic. Nearly ten percent of the entire Roman army had been wiped out in a few days. The legion numbers XVII, XVIII, and XIX were considered so unlucky that they were never used again. In the following years, the brilliant general Germanicus, nephew of the new emperor Tiberius, led several punitive campaigns deep into Germania. He inflicted defeats on Arminius’s coalition, recovered two of the three lost eagles, and found the haunting battlefield, where he gave the bleached bones of Varus’s men a proper burial.

But despite Germanicus’s successes, the strategic decision was made. Tiberius recalled him and abandoned the goal of conquering Germania. The cost in blood and treasure was deemed too high. The Rhine and Danube rivers would become the permanent northern frontier of the Roman Empire.

A Legacy Carved in Blood and Forest

The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest was one of the most decisive battles in world history. Arminius’s masterful betrayal and his perfect exploitation of terrain and weather completely overwhelmed a superior military force. The defeat forced the world’s greatest empire to accept a limit to its power.

This decision had profound consequences. By keeping Rome out, the Germanic tribes were able to develop their own distinct languages, laws, and cultures. This independence from Romanization laid the groundwork for the future of Germany, England (through the Anglo-Saxons), and Scandinavia. The battle didn’t just destroy three legions; it carved a cultural and political line across Europe that can still be traced to this day, a permanent reminder that even the mightiest empires can be defeated by a fierce will for freedom in a dark, unforgiving forest.