A Collision of Empires

To understand the Battle of Talas, we must first picture the world of the mid-8th century. Two superpowers dominated the Eurasian landmass, their influence expanding until they were destined to meet.

The Expansive Tang Dynasty

In the East, China’s Tang Dynasty was enjoying its golden age. Under the long reign of Emperor Xuanzong, its culture was cosmopolitan, its economy was booming, and its military was pushing its borders further than ever before. Tang armies, composed of a diverse mix of ethnicities, had marched west, projecting power deep into Central Asia. They controlled the lucrative Silk Road routes through the Tarim Basin and had established a system of protectorates, demanding tribute from the small kingdoms and city-states of the region.

Leading this westward charge was Gao Xianzhi, a brilliant general of Korean descent. He was audacious and effective, a symbol of the Tang’s meritocratic and multi-ethnic military machine. His ambition, however, would prove to be the spark that ignited the conflict.

The New Power: The Abbasid Caliphate

In the West, a political earthquake had just occurred. In 750 AD, the Abbasid family had overthrown the Umayyad Caliphate, moving the heart of the Islamic world from Damascus to their newly founded capital, Baghdad. The Abbasids were energetic and expansionist, eager to consolidate their control over Persia and push their influence eastward into the lands of Transoxiana (modern-day Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and surrounding areas).

Fueled by a revolutionary zeal and a sophisticated administrative structure inherited from the Persians, the Abbasids were a formidable force. They saw the Tang’s encroachment into what they considered their sphere of influence as a direct challenge.

The Spark in the Ferghana Valley

The collision course was set, and the trigger was a local dispute. The ruler of the Ferghana Valley, a Tang ally, was in conflict with the neighboring king of Chach (near modern Tashkent). General Gao Xianzhi intervened decisively. He besieged Chach and, after brokering a surrender with a promise of safe passage, he broke his word, sacking the city and executing its king.

The slain king’s son escaped. Furious and seeking revenge, he fled to the Abbasids and pleaded for help. For the Abbasid governor, Ziyad ibn Salih, this was the perfect pretext. He amassed a large army and marched to meet the Tang.

The Battle of Talas River

In July 751 AD, the two imperial armies met near the Talas River, in what is today the border region of Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Gao Xianzhi commanded a force of around 30,000 soldiers, a mix of Tang regulars and allied troops from local tribes, most notably the Karluk Turks.

The Abbasid army, led by Ziyad ibn Salih, was significantly larger. For five days, the battle raged. The smaller but disciplined Tang force, particularly their expert archers, held their ground against the Abbasid assaults. The outcome hung in the balance.

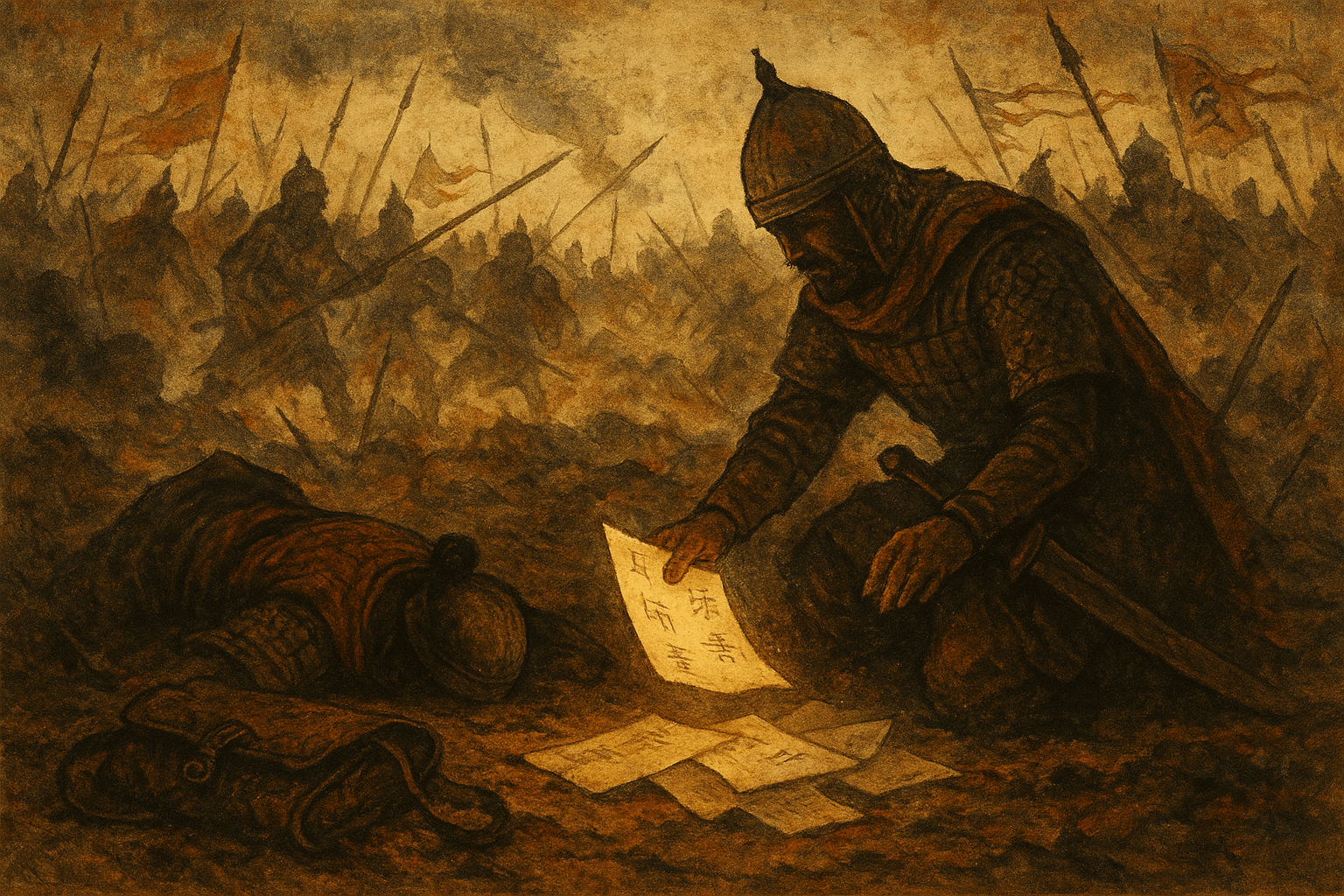

The turning point was a sudden and decisive betrayal. The Karluk Turks, who made up a significant portion of Gao’s army, switched sides mid-battle. They attacked the Tang forces from the rear while the Abbasids launched a frontal assault.

Caught in a pincer movement, the Tang lines shattered. The defeat was catastrophic. Gao Xianzhi barely managed to escape with a few thousand men. The rest were killed or, crucially for our story, taken prisoner. For the Tang Dynasty, the defeat at Talas, combined with the devastating An Lushan Rebellion that erupted at home just a few years later, marked the end of their westward expansion for good.

History’s Most Important Prisoners of War

Among the thousands of Tang soldiers captured by the victorious Abbasids were men of various trades. And among these artisans were skilled papermakers. While the Abbasid commanders celebrated their military victory, they quickly realized the true prize they had won.

At this time, the Islamic world primarily used two writing materials:

- Parchment: Made from treated animal hides, it was durable but incredibly expensive and labor-intensive to produce.

- Papyrus: Made from reeds, it was cheaper but brittle and could only be cultivated in the Nile Delta, making supply lines long and unreliable.

The Chinese, by contrast, had possessed the secret of paper for centuries. They manufactured it from readily available materials like mulberry bark, hemp, and old rags. Chinese paper was light, flexible, cheap, and perfect for both writing and mass production.

The captured papermakers were taken to the bustling Silk Road hub of Samarkand. There, under Abbasid patronage, they were put to work, and the first paper mill outside of China was established. For the first time, Arabs and Persians learned the secrets of turning pulp into smooth, white sheets of paper.

How Paper Fueled a Golden Age

The impact was immediate and revolutionary. From Samarkand, the technology spread like wildfire across the Islamic world. Baghdad, Damascus, Cairo, and Fez soon had their own thriving paper mills. The availability of cheap, plentiful paper was a catalyst that helped ignite the Islamic Golden Age.

- Bureaucracy and Governance: Complex administration requires extensive records. Paper allowed the Abbasid Caliphate to run a sprawling empire with a level of efficiency previously unimaginable. Decrees, tax records, and correspondence could be produced and distributed with ease.

- Scholarship and Translation: Paper untethered knowledge. The great translation movement, centered in Baghdad’s House of Wisdom, could now flourish. Scholars translated the works of Greek, Persian, and Indian thinkers—from Aristotle and Plato to ancient mathematical treatises—onto paper, preserving and expanding upon this knowledge.

- Literacy and Commerce: Books were no longer a luxury item for the ultra-wealthy. Libraries grew, education spread, and a vibrant literary culture emerged. Merchants used paper for contracts and accounting, fueling economic growth.

The journey didn’t end there. From the Islamic world, papermaking technology traveled into Europe through Al-Andalus (Islamic Spain) and Sicily by the 12th century. It slowly replaced expensive parchment, laying the essential groundwork for an intellectual revolution. Without the widespread availability of cheap paper, Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press in the 15th century would have been a fascinating but ultimately niche invention. Instead, it changed the world—a change made possible by prisoners of war from a forgotten battle centuries earlier.

The Battle of Talas, therefore, stands as a powerful reminder. It was a military defeat for one empire and a victory for another. But its true legacy lies not on the battlefield, but in the quiet workshops of Samarkand, where a simple technology began a new journey, carrying with it the future of knowledge, administration, and human progress.